The Professor Doth Protest Too Much, Methinks

I am deeply skeptical. When I read that Shakesepeare didn’t write Shakespeare in a book written by someone I trusted, I didn’t believe it. The book gave a good argument, but it didn’t convince me. I read a couple more books written by reputable professionals expanding on the argument and was still not convinced. Then I read the other side of the story. I read several books by eminent Shakespeare scholars explaining why all the “authorship questions” were just so much nonsense.

Now I was convinced. The eminent Shakespeare scholars seem to know Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare. They seem desperate. They say bizarre things that don’t make sense; they make circular arguments that are way, way beneath them; they look for easy rhetorical points to score while studiously ignoring the meat of the main arguments; they take nasty potshots when they have nothing left to say.

Here are six little bites to give you an idea why there is a Shakespeare Authorship Studies Center at Concordia University and why Roger Stritmatter got a Ph.D. at UMass Amherst studying the authorship question and why the famous Shakespearean actor Sir Derek Jacobi believes the traditional attribution is totally absurd.

Six Brief Bites

(1) William Shakespeare, unfortunately, never existed. It sounds like a strong thing to say, but details really do matter. A man baptized William Shakspere who signed his last will and testament William Shakspere and who never used the name William Shakespeare was an actor in a company that put on Shakespeare plays. But the actor had the wrong name.

If that was all, it would be nothing. One would simply explain the difference in the personal spelling and the publication spelling in any one of a hundred different ways and move on. But it isn’t all.

(2) Shakspere tried to write his name a few times. The signatures, such as they are, survive. He couldn’t write his own name. His signature looks nothing like the smooth, flowing signatures of other professional Elizabethan writers who wrote millions of words without benefit of word processing and therefore, amazingly, were pretty good with a pen.

You can take one look at Shakspere’s signatures and know he is not a writer. No handwriting expertise is necessary.

(3) Shakspere wasn’t referred to as a writer by anyone who knew him until seven years after his death when he magically turned into the famous writer Shakespeare. He was referred to as a businessman and as an actor, but not as a writer.

No other Elizabethan writer had to die in order to become a professional writer.

(4) Shakspere was born in 1564 and died in 1616 and in all that time never wrote so much as a letter to his family, to a business associate, or to a “fellow” writer. He didn’t receive any letters either. He owned no books.

A great deal of material survives even for writers that were far less famous in their lifetimes than Shakespeare. No other Elizabethan writer left behind zero personal items indicating their profession. The “bad luck” theory doesn’t hold water.

(5) The majority of the non-history plays are set in Italy with extraordinary local detail. Mainstream authors have tried mightily to suggest that Shakspere could have learned enough about Italy from books and travelers to write the Italian plays.

Of all the arguments the mainstream has lost, this one is the most spectacular. To read the mainstream’s claims that books and travelers were sufficient set against the details Shakespeare includes in the Italian plays is like watching a man engage in a boxing match with an angry elephant.

(6) Shakespeare’s two epic poems were dedicated to the Earl of Southampton and, subject to interpretation, the earl’s politically charged personal life appears to be revealed in the sonnets including some things that would have been state secrets. If the sonnets really contain inside information about the results of Southampton’s attempt to control the royal succession, Shakspere-the-businessman-from-Stratford can be confidently excluded as an authorship candidate.

The Southampton interpretation of the sonnets, if true, explains parts of Southampton’s political life that history knows only the outlines of.

Six Bites and You’re Out

(1) Shakspere was a family name. William was baptized Shakspere as were all seven of his siblings. William signed his name as well as he could, Shakspere. He never used Shakespeare. On the other hand, Shakespeare was used consistently on the published works.

Spelling was quite variable in those days, including the spelling of names. The consistency of Shakspere for personal documents and Shakespeare as a publication name wasn’t perfect, but it was more than clear and even the deviations from Shakspere are almost all phonetic spellings such as the Shagspere on his marriage certificate. No other author avoided using his publication name in his personal life the way Shakspere did.

(2) Shakspere couldn’t write his own name. Take a look.

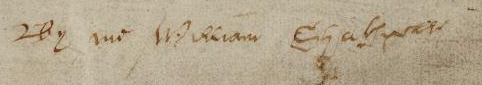

Last page of will. The “By me William” part was obviously written by someone else. Shakspere may have been sick at the time.

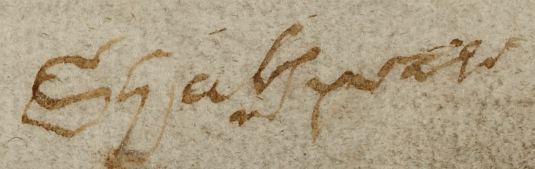

Closeup of the part Shakspere wrote.

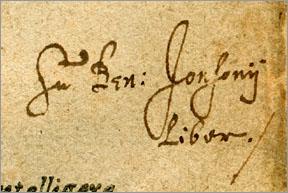

Ben Jonson was a writer and had a smooth hand.

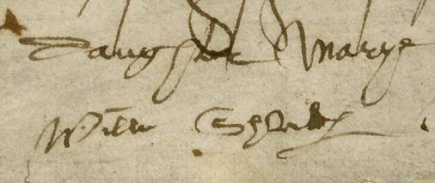

Five years before Shakspere died he tried to sign a legal document.

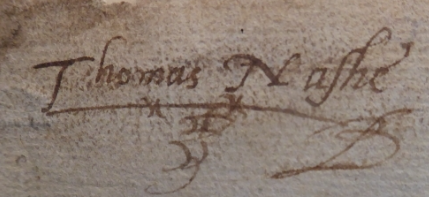

Thomas Nashe, like every other professional writer of the time, had some facility with the pen.

Shakspere’s shaky signatures are reminiscent of Raymond Dart’s discovery in the 1920’s. He discovered a fossil of a bipedal ape before the mainstream was willing to consider such things. For our small-brained bipedal ancestors, the spine enters the skull along the midline rather than along the back. No microscope is needed. One look at the skull and the difference is instantly visible. The same is true for Shakspere’s signatures. Dart was ignored by his fellow researchers for twenty years simply because his discovery was destined to change the way they thought about human evolution. Shakspere’s signatures have been studiously ignored for two hundred years although various perfectly good excuses — maybe he was sick or distracted or someone else was doing the writing — have been proposed.

(3) If it were just the name and the handwriting, that still wouldn’t be enough to convince a reasonable person that we were all fooled by the greatest hoax in history. But Elizabethan writers were ALWAYS described as writers and/or referred to as writers by people who had physical contact with them. It was a long time ago, but such documents survive for every Elizabethan writer EXCEPT Shakspere.

Shakspere biographer Schoenbaum marvels that Shakspere’s “townsmen” didn’t seem to know he was a writer — he says they didn’t “trouble their heads about the plays and poems.” Schoenbaum goes on to say, “business was another matter.” Schoenbaum was immune to his own research.

Diana Price picked up where Schoenbaum left off and verified that what the classic biographers marvel at — Schoenbaum was far from the only one — is indeed worth wondering about: among 24 Elizabethan writers plus Shakspere that Price studied, ONLY Shakspere was never referred to as a writer by those who knew him.

(4) In addition to the lack of references, there is no evidence Shakspere wrote anything at all. All of his letters (if any), written or received, have been lost. All of his books (if any) were lost.

Shakspere died in a big house (a mansion) full of stuff and had two children and left a long will. No books were mentioned, no quills, no inkwells, no bookshelves, no desks. No manuscripts or writing of any kind were part of his estate.

The fact that a name similar to his appears on published works, despite repeated circular reasoning indulged in by ivy-league professors, means nothing if there is nothing to connect him to those works. Being an actor in a play whose author has a name similar to yours does not make you the author. The arguments made by experts using Shakspere’s acting as an indication that he was a writer are simply embarrassing.

Shakspere’s two grown daughters were demonstrably illiterate. Other writers not only saw to it that their children could read their work, they also left bequests to ensure their grandchildren would be taught to read. Such a bequest would have been totally out of character for Shakspere.

Let’s do some very elementary statistics. Elizabethan writers left behind documents roughly half of which relate to their profession. For some writers, it was a little less than half of documents, for others it was a little more than half. Roughly speaking, for an Elizabethan author, a document referring directly to writing was a coin flip: heads it is some mundane part of life; tails it has something to do with their chosen profession.

Shakspere had seventy surviving documents. ZERO documents having to do with writing requires astronomical bad luck. You could flip coins long enough to watch single-celled life evolve into mammals without flipping seventy tails in a row.

(5) Shakespeare knew so much about Italy that he could mention the Duke’s Oak (capitalized) in “Athens” and confuse even modern scholars equipped with modern tools.

It took Richard Roe physically going to Italy and visiting a town the Italians have always called “Little Athens” and stumbling upon the Duke’s Oak (capitalized) which is an entryway to a forest constructed centuries ago. Now we understand the reference, finally. The Duke’s Oak was capitalized in the original Shakespeare but the capitalization was never understood and was sometimes removed. Shakespeare’s Italian plays are filled with similar minute detail.

The necessity of placing the commoner Shakspere in Italy at some point troubles the mainstream hence their desperate pleas that you don’t learn about the level of detail in the Italian settings.

(6) Finally, Shakespeare seems to have written a series of sonnets about Southampton’s life in addition to his two epic poems lavishly dedicated to the earl.

Shakespeare, the author, called his subject his “lovely boy” in Sonnet 126. In Sonnet 10, he asked him to “make thee another self for love of me.” Pretty intimate stuff.

Shakespeare who was obviously extremely close to Southampton and knowledgeable about his situation was deeply preturbed when Southampton was sentenced to death for high treason and tossed into the Tower where Shakespeare visited his imprisoned love only to find that when he returned home, he could not sleep.

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired;

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind, when body’s work’s expired:

For then my thoughts–from far where I abide–

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see:

Save that my soul’s imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which, like a jewel hung in ghastly night,

Makes black night beauteous, and her old face new.

Lo! thus, by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for myself, no quiet find.

In Sonnet 87, the line “the charter of thy worth gives thee releasing” could mean a lot of things. The references to “misprision” and to a “better judgment” seem apt as misprision of treason (knowing about it but not reporting it) is not a capital crime and Southampton certainly got a better deal than the Earl of Essex or the four knights who were all slaughtered.

Shakespeare is overjoyed in Sonnet 107 when Southampton, who was “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom,” was released. “The mortal Moon hath her eclipse endured” and “incertainties now crown themselves assured.” That is, the Queen (often poetically compared with the Moon) had died and James had ascended the throne.

After he became King, James promptly released Southampton and restored his Earldom and all his lands. No reason was given.

Southampton and his ally, the Earl of Essex, had tried to control the succession. Bad idea. History does not tell us what was so special about Southampton that he got to keep his head (not to mention his Earldom).

The same summer he was released, Southampton was made captain of the Isle of Wights AND also a Knight of the Garter. Again, this is not at all understood by history.

Sonnet 106 has the following suggestive lines which may or may not mean anything:

When in the chronicle of wasted time

I see descriptions of the fairest wights,

And beauty making beautiful old rhyme,

In praise of ladies dead and lovely Knights,

Later in the sonnet, Shakespeare speaks of “prophecies” and “prefiguring” and “divining.” Shakespeare seems to have known what was going on behind the scenes.

IF the speculations indulged in in this “bite” regarding Shakespeare’s knowledge of Southampton’s fate are true, we can eliminate Shakspere as an authorship candidate.

Conspiracy Theory

With James firmly in power, in 1623, the Earls of Montgomery and Pembroke gathered together 24 unpublished (or badly published) Shakespeare plays and 12 previously published plays, recruited two of Shakspere’s acting buddies, hired Ben Jonson, and got a publisher. They preserved the work of whoever wrote the plays in what we call the First Folio.

At the same time, they either made it look like Shakspere was the author, connecting the actor with the work for the first time in the preface to the First Folio or, if you prefer, they cleared up the terrible confusion that had dogged poor Shakspere all his life causing people to think of him as merely an actor and hard-nosed businessman when he was really the greatest writer in all England.

The earls and their team also had a monument built praising Shakspere as Virgil, Socrates, and Nestor rolled into one. The monument spells the name “Shakspeare” which may be a fortuitous error being neither Shakspere nor Shakespeare.

As hoaxes go, it wasn’t a very good one. The paper trail left by Shakspere during his lifetime is pretty much irrefutable: he wasn’t a writer.

On the other hand, reasonable people can disagree. There is another side to the story, as always.

Maybe Shakspere didn’t like the name his publishers used and maybe that explains the gap between his personal name and his published name. Maybe he simply had bad handwriting or maybe the signatures were scrawled under difficult conditions. Maybe his unusual dual career as an actor/writer caused people he knew to refer to him as an actor or businessman rather than as a writer during his lifetime. Maybe all of his letters were unfortunately lost. Maybe he made arrangements for his books outside of his will. Maybe the mention of “household stuff” in his will included his bookshelves and writing desks. Maybe he didn’t teach his daughters to read because they were country girls and/or he was too busy in London to bother. Maybe he went to Italy with some nobleman or other during the years for which we have no record of him (1585-1592). Maybe he had a relationship with Southampton for which there is unfortunately no independent evidence. Maybe the sonnets are not about anyone in particular and should be treated as fiction and not connected to the historical record.

Occam’s Razor

Occam’s razor is a wonderful thing. What is the simplest assumption for us to make? All five “bites” based on hard evidence can be explained. The sixth bite is speculative (although you might not think so once you read the sonnets) and doesn’t require an explanation.

Should we explain away the five bites with a million maybe’s and hope the sixth is nonsense or would it be simpler to imagine an author who could write his name, who wrote letters, who owned books, who went to Italy, who knew Southampton, and who used a pseudonym?

Here are two lines from Sonnet 81.

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die:

When this was written, “Shakespeare” had already taken his place amongst the most famous writers in English history.

Of course, one can argue that any cover-up theory is full of unknowns and unknowables. What was the reason to go to all the trouble of a cover-up? Did King James want to keep Southampton’s claim to the throne (assuming he had one) out of history? What was the nature of such a claim? Does this explain the commutation of his sentence and his release from the Tower? Were the goodies he got after being released some kind of bribe to purchase his silence? We’ll never know.

The timing of Shakspere’s arrival in London is a problem if you want to believe in the cover-up (conspiracy) theory. Why did the first Shakespeare performances occur in the early 1590’s coinciding with Shakspere’s arrival at about the same time? There is a 1589 reference to “whole Hamlets of tragical speeches,” which might help disqualify Shakspere, but there is no record of any 1580’s performance of any Shakespeare play. If you want to prove Shakspere wasn’t the author, a firm record of a performance or two or three or four in the 1580’s, well before Shakspere arrived in London, would be very helpful.

If we ignore the tragical speeches comment, the timing for the early performances of Shakespeare plays makes it look like Shakspere may actually have written them. Was Shakspere really nothing more than a semi-literate country boy when he showed up in London just as Shakespeare the author was becoming well known?

The problem here is not that Shakspere couldn’t have written the plays. The problem is that the mainstream try to argue that there is NO issue, that the whole idea that Shakspere wasn’t Shakespeare is ridiculous and shouldn’t be discussed. But whether one looks at his signature or the Italian plays or the Sonnets or the comparison to the records of Elizabethan writers or Shakspere’s extensive business-related documentation or any of the other rock-solid reasons to doubt the traditional attribution, there is simply no rational way to argue that there is NO issue here.

The mainstream scholars are, essentially, fools even though they are very smart.

The professors doth protest too much, methinks.

Re paragraph 3 of “Conspiracy Theory”: The monument in Trinity Church refers to the subject as ‘SHAKSPEARE’, not ‘SHAKESPEARE’.

I was just seeing if you were paying attention . . .

Thanks,

Thor

Dropping out the “e” in the plaque’s truncated spelling for Shakespeare kept intact a pithy steganographic message, identifying “Shakspeare” as “De Vere”. (David Roper discovery)

Can you elaborate or provide a link?

The grid that shows the Shakspeare plaque’s ulterior message is reproduced here: http://www.wjray.net/shakespeare_papers/tabooing-de-vere.htm

You can read Roper’s analysis of the plaque’s nearly nonsense message, with a meaningful identity solution embedded, in his “Proving Shakespeare in Ben Jonson’s Own Words’, pp. 3-16.

There are special spellings and other irregularities in the message on the cenotaph plaque at the Trinity Church in Stratford. No one knows who constructed the message, but the surface syntax is similar to Jonson’s other dedication language. He was known as one of the cleverest encryptors of his time, utilizing the Equidistant Letter Sequence system employed by the diplomatic service under Cecil. He worked as an employee of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, who controlled the Revels and influenced the printing of dramatic manuscripts. Thus one of his assignments was to create a message in the seeming encomium at Stratford, and another was to promptly communicate the same author message in the First Folio front matter. He did this both in the introductory poem and the facing “portrait” of the supposed author. Since the engraving does not depict a human being, lacking the physiognomy of the species, it must be interpreted as a puzzle to solve. I did this is a later essay in my chapter, Shakespeare Papers at wjray.net.

You are doing good things. Just remember that much labor has preceded your inquiry which would be valuable information as you educated yourself and your readers. with best wishes, WJ Ray