Scipio Who?

Most days your typical crew of mainstream scholars are models of good behavior — coherent, intelligent, professional. But one day a colleague challenges a cherished premise. Groupthink manifests: the denizens of the sometime-dignified professorial class strip off their clothes and smear blood upon their naked bodies. They gather in silence, ancient instincts not so deeply buried as we would like to believe.

The hearts of the professors beat in synchrony thirty-six times. On the thirty-sixth beat, a terrific battle cry rises and the professors rush — sprinting, screaming, blood streaming — into the office of the premise-challenger who looks up from their desk the picture of nonplussed. Innocently questioning a premise, not claiming certain knowledge, pointing out a few anomalies, the poor premise-challenger most certainly did not expect some sort of inquisition.

It would be reasonable to ask at this point if such things really happen: literally, no; metaphorically, yes.

A century ago, premise-challenger Raymond Dart innocently said “look what I found!” His fellow archeologists made every effort to bury him alive but soon desisted and then simply refused to look at his find. Twenty years passed. In the interim, Alister Hardy, a marine biologist not aware of Dart’s find, had an idea. Still a wet-behind-the-ears professor, he revealed his dangerous thoughts to a few of his friends who, in an effort to protect him, pinned him to the floor of his living room. They let him up only after he promised to remain silent about his idea for thirty years. Hardy told his friends they were being overprotective: “It isn’t that bad,” he said. But his friends wouldn’t budge. They took turns holding him down until he finally gave in and gave his word. Hardy kept his promise even though it was made under duress.

Decades later, with Dart’s discovery finally accepted but its implications thoroughly unplumbed, Hardy finally said what needed to be said. Dart’s discovery and human physiology were clues to the answer to the biggest question in human evolution: what caused the human line to split off so dramatically from the evolutionary paths followed by every other primate? To Hardy, the answer seemed obvious, especially considering what Dart had discovered.

By then Hardy had been knighted, but, needless to say, Sir Alister Hardy was ignored anyway. Hardy was comforted by the fact that knighthoods can’t be taken away but it wasn’t fun for him to contend all the nastiness thrown his way: his idea, twisted and changed, was ridiculed. In some cases, even his own colleagues joked about a theory far from the one he had put forward. Some experts criticized his actual idea but even they did not exhibit scientific skepticism: they said his idea was not worth discussing but didn’t offer any reasons worth repeating.

By then, every professional evolutionary theorist knew that our ancestors did NOT evolve toward bipedal locomotion because tool use created evolutionary pressure for two free hands. Everyone knew the split of the human line from the other primates was a huge mystery. Experts entertained any number of wild ideas to resolve the mystery including ideas involving unprecedented steps in evolution that had not happened with any other species. Experts seemed wedded to the idea that humanity had carved out a unique path for itself. Hardy assumed that humanity had followed an evolutionary path followed by many other mammals throughout evolutinary history. It was almost as if his theory was too obvious to be worthy.

Enter Elaine Morgan, talented amateur. She read about Dart’s amazing discovery: millions of years before humans appeared, millions of years before tools became the central feature of human existence, millions of years before our brains enlarged, our evolutionary line was occupied by bipedal apes, very real Sasquatches, Bigfoots, Yetis, and/or Yerens as they are called today in various cultures. Sasquatch is a legend, but bipedal apes, one of whom left a fossil waiting for Dart’s shovel, were real; they paved the way for their “wiser” bipedal descendents with the big brains who call themselves Homo Sapiens.

Morgan also read about Hardy’s insight. She realized that Hardy’s theory would cause one to expect just what Dart found: bipedalism evolving long before tool use. She realized that the “man-the-hunter” image in everyone’s mind was far from the reality: hunting did NOT make us what we are today. She marveled at Dart’s find and Hardy’s parallel insight. Why didn’t everyone know about it? It should be front-page news.

Elaine Morgan found herself face to face with the concerted efforts on the part of Dart’s and Hardy’s colleagues to squash out-of-the-box thinking and out-of-the-box hard evidence (!) and stick with old theories or slightly altered versions of old theories. She was, to put it mildly, not happy with the studied indifference, frozen immobility, and intellectual barrenness of the professors in whom thoughtful people like her (and you and me) perforce put their trust. She wanted (needed!) fertile discourse, productive exploration, and mental stimulation but instead saw academia hobbled by what I call the “Star Wars Writers Effect” — mindless repetition of what worked in the past. Book after book about human evolution ignored Dart and Hardy.

Tired with all these, Elaine Morgan felt her options limited. She felt, in fact, that she had no choice but to become a warrior. So she sharpened her spear and brandished it (rhetorically) at the cartoon image of man-the-hunter still being passed off as science by professors who were better at politics than science. Morgan wrote a bestselling book called The Descent of Woman showing that politics could be a double-edged sword. She carved out a permanent place for herself as the bane of mainstream archeologists and anthropologists everywhere.

If Morgan’s title raised eyebrows, the contents of her book raised the dead. One has to admit she was tactless. But it is a better thing, I Aver, to be enduring than it is to be endearing. And yet Morgan, like Dart and Hardy before her, eventually played nice, patiently putting forward ideas while making efforts to unruffle the professors’ foever ruffled feathers. She told me toward the end of her life that she regretted her previous gladiatorial stance and I respected her regret. Nevertheless, I wouldn’t trade The Descent of Woman for a whole library of mainstream anthropology.

It’s been almost a full century since Dart’s stunning find and Hardy’s parallel insight and another half a century that the mainstream has been face to face with Morgan’s relentless logic and impolitic truths. And here we are still stuck with a long series of theories of human evolution — none of which are as good as Hardy’s — proposed and discarded one after another. Three heroes are dead, the professors (Daniel Dennett at Tufts excepted) remain firmly anti-Hardy, and we in the general public are the losers.

I will not here delve into the Dart-Hardy-Morgan revolution-that-wasn’t. Suffice it to say that humans, physiologically speaking, do very well in coastal environments. It was this that Hardy pointed out to his friends almost a hundred years ago; it was this that led to him being pinned to his living room floor.

The mainstream will have none of it and it’s been almost a hundred years so capitulation seems appropriate. I AGREE with the mainstream that when a human pearl diver descends for her living one hundred feet or more beneath the waves without need of technology, this feat of humanity should NOT be considered relevant when discussing human evolution. And while it is true that human babies, properly exposed, easily dive ten feet to the bottom of a pool before they can walk, this, we Aver, tells us NOTHING about the evolutionary steps our ancestors took millions of years ago which obviously did NOT take place in a coastal environment.

Il sangue scorre troppo freddo (quasi tutti i giorni) verrà sventatamente versato : One’s blood runs too cold (most days) to be blithely spilled.

Allora, è meglio aspettare (quasi tutti i giorni) : And so, it is better to wait (most days).

What Is Reasoning?

I must apologize to my readers for lapsing into bad Italian. Most importantly, I must apologize for the images sketched above. The images are either hyperbole or understatement — I am never sure which — but they are not the hard facts my readers have every right to demand of me and so I am truly sorry if you feel any of your time has been wasted. Let me now atone for my literary sins with a brief foray into respectable formality.

We can state with some certainty that it — the will to block the winds of change — is a well-studied phenomenon. It is so well studied, in fact, that we shall not study it here so much as we shall exemplify it. But first, by way of the promised atonement, I will tip my hat to the philosophers who have studied this phenomenon. Let us call it the Dart-Hardy-Morgan effect: the sad reality in which proponents of new ideas die before their wisdom can be received.

Philosophers tell us that baked into our social, cultural, scientific, historical, educational, and political structure is a sort of “Zeroth Law,” a law which comes before all others, a law saying incremental progress is safest. Leaps are to be avoided, not merely skirted carefully or examined skeptically but run from as one avoids a plague. Leaps are dangerous. A premise, on the other hand, is a loved child.

The premise-child must be protected at all costs. One abandons a premise-child only when one’s own death leaves one no other choice.

Thomas Kuhn, in his famous book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, talked about the importance of premises and especially groups of related premises he called “paradigms.” A paradigm in Kuhnian philosophy has many definitions one of which is this: “a foundation of indubitable usefulness and exaggerated permanence which underlies a specialist’s understanding of the universe.” Kuhn explained that paradigms are useful because they narrow the field of view in a productive way thereby allowing a group of experts to pick out important experiments and make steady progress as opposed to endlessly exploring an infinte array of possibilities most of which lead to dead ends.

Electricity, for example, was made practical without scientists knowing exactly what it was composed of (even today, we can describe electric charge only as a property possessed by charged particles) because the scientists found a powerful paradigm which helped them choose the most productive experiments. So paradigms are good things, necessary things. The problem with a paradigm is that its limited validity tends to be exaggerated which can lead to dogmatism which can then, ironically, impede progress.

But paradigms are limited in scope and are routinely not so much replaced as encompassed by a new paradigm which contains within it the old paradigm as a sort of approximation. These “paradigm shifts” are inevitable because even powerful mathematical, diagrammatical, and logical conception of reality is merely a model of that reality as opposed to being reality itself. On the other hand, a paradigm might be more precarious than the word “limited” implies: sometimes a paradigm shift is not merely an advance in our understanding but represents an egregious error being corrected.

However it happens and whatever the level of drama that attends it, the popular notion of the paradigm shift which came out of Kuhn’s book involves proud scholars changing their tune. It might be relatively painless as when Einstein’s theory of gravity triumphantly predicted wobbles in mercury’s orbit that Newton’s theory would never have imagined and astonomers confirmed Einstein’s theory causing newspapers and the physics community to immediately celebrate the new science of warped space. But sometimes, especially when the old paradigm is not just limited but actually looks downright silly in hindsight or was (perish the thought) flat-out wrong, a paradigm shift is excruciating.

No one wants to admit they have been barking up the wrong tree for decades especially if it’s been killing people.

Stomach ulcers and many stomach cancers are caused by bacteria not stress and stomach acid. In 1981, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren had to deal with colleagues who treated their research proving that simple fact as if they were proclaiming the earth to be flat (that’s how Marshall described it). The wrong paradigm had dug itself in so deeply that Marshall ended up having to purposely infect himself causing painful and dangerous ulcers in order to then cure himself and finally prove in 1985 that an entire industry of ulcer treatment was based on a false premise. It is not known how many people died or how long the cure was delayed because young scientists who questioned the premise were told to stop saying the earth is flat.

Telling credentialed professionals not to question the premises is irrational. Of course the person questioning the premise will often be wrong. So what? A new theory that is wrong or not as useful as the old theory nevertheless solidifies our understanding of the world when it, the new theory, is examined and perhaps rejected by open-minded people. And what if the new theory is correct? That’s a breakthrough. In any rational system, credentialed professionals would be encouraged to take risks, to question premises, to stick their necks out. No one would pin anyone down to any living room floors the minute they say, “I have an interesting idea . . .”

We define here “Kuhnian irrationality” as the social and cultural reluctance or the social and cultural outright inability to question a premise manifested by gray-haired professors plugging their ears while shouting “nyah, nyah, nyah I’m not LISTENING.” We take it as self-evident that premises should be questioned and we hope Professor Kuhn, who died in 1996, doesn’t mind our use of his name to encapsulate the key concept of the present work.

Dart, Hardy, and Morgan questioned a premise and watched helplessly as their insights ran aground on the sholes of Kuhnian irrationality where they founder to this day. Alfred Wegener questioned a premise about geology and, in fact, proved beyond doubt that the continents were once a single landmass and of course ran into Kuhnian irrationality. Wegener’s stunning revelation has made the transition from crazy idea to common knowledge but Wegener didn’t live to see it happen.

Marshall and Warren won a Nobel Prize but did not change the way we view premises or out-of-the-box thinking or “crazy ideas” that might not be so crazy. This is a work in progress. How can we move forward? How can we open closed minds? What do we do about Kuhnian irrationality?

We turn now to what I consider the touchstone of Kuhnian irrationality. This is an extreme example showcasing beautifully and bloodily the susceptibility of anyone, no matter how intelligent, responsible, and accomplished, to the siren song of a false premise. Its inherent drama and unspeakable tragedy make the point as sharply as it can be made. After collecting, as it were, our touchstone, we will will move on to what I consider the most amazing case of Kuhnian irrationality still in process today. But first, the horror.

It was January 1986 and colder in Florida than it is ever supposed to get with temperatures in the low twenties Fahrenheit. The space shuttle launch was not quite a toss-up. By this I mean that the seven humans in the cockpit, had they heard the engineers discussing the problem, would have immediately refused to launch. If Christa McAuliffe’s high school students heard what the engineers were saying, they would have demanded the launch not take place. It was obvious. It was obvious that risking one’s life on a coin toss would be a better deal than sitting in the cockpit of the space shuttle on that cold day.

It was too cold to launch and the engineers knew it.

It was not too cold in the sense of being too cold to go out without a coat — it was, but that’s not what we’re talking about. It was too cold in the sense of being too cold for a corpse to rot but that still does not tell what must be told. It was cold the way an executioner’s eyes are cold. We are closer to the right metaphor but we aren’t there yet.

It was as cold as an equation. Do you see what I mean? Maybe you don’t, but fear not, you soon will. Nothing is colder than an equation with the possible exception of the moment of death itself.

Truth, Lies, and O-Rings tells the horrific story in microscopic detail. The engineers at Morton Thiokol in Utah knew the O-rings were a problem. A year before, one of two crucial O-rings had been breached during a somewhat chilly fifty-three-degree launch. If both O-rings go, everyone dies. Since it was thirty degrees colder that day than it was a year before when they had come too close for comfort to losing the shuttle, Morton Thiokol, on the advice of the engineers it employed not to mention common sense, cancelled the launch.

That’s right, they cancelled the launch.

But then a whole flock of premises came home to roost: the space shuttle is perfectly safe; we’ve had a lot of safe launches; there are many redundancies in our systems; the engineers can’t prove the O-rings will leak at low temperatures; the problems with the O-rings aren’t yet fully understood and the shuttle has been launching safely for years; it’s possible there’s nothing to worry about; the O-ring data is inconclusive.

It was possible that the shuttle could launch in the cold. Of course it was possible. Anything is possible. How long does it take, you might wonder, for the possible to become all-but-certain? Decades ago, Morton Thiokol taught us the answer: thirty minutes.

During the thirty minute conference at Morton Thiokol when the engineers and the managers followed the NASA administrator’s urging to rethink the cancellation, the engineers admitted to the managers they couldn’t prove the O-rings would be affected by temperature. They admitted the data they had was inconclusive.

So the engineers couldn’t prove the shuttle unsafe. Therefore, it was safe. (Yes, really.)

One low-ranking engineer, not falling for the reversal of the burden of proof perpetrated by his four bosses, stood and approached them. He walked right up to them paper and pencil in hand. He tried to explain his concerns. He drew a diagram. He was ignored. He could see that he was being ignored. He gave up. He returned to his seat. Another engineer tried the same thing with the same result.

The two engineers would never forget their failure to make themselves heard. Their palms sweaty, they watched as the cancellation was undone. A few hours later they would watch, their palms still sweaty, as the shuttle launched with nothing between the seven astronauts and death except a cold equation: the flexibility of rubber is inversely proportional to temperature.

Ignition was successful. The shuttle defied gravity at T minus zero. Seventy-three seconds later, etched with terrifying beauty against a clear sky, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded. The cockpit, intact with the astonauts still alive, arced into the Atlantic ocean at 200 mph. The crew, including high school teacher Christa McAuliffe, died instantly.

After the dust and debris had settled, after the dead were buried, while the nation mourned, Sally Ride sat with her colleagues on the presidential commission tasked with finding out what the Hell had happened. They would never understand. The engineer who wrote Truth, Lies, and O-Rings never understood. I don’t understand. To know in your bones what happened — to know how intense questioning over every tiny detail could be suddenly converted to mindless indifference to a critical problem — you would have to go insane.

Everyone in Dr. Ride’s profession — the astronauts, the engineers, the administrators, the bosses, the employees, the newbies, the old hands, everyone — knew in their bones that the people concerned about safety don’t have to prove anything. They knew it. They knew it one moment and then the next, like a sudden death, they acted as if their heads had been suddenly emptied of all thought.

Sally Ride looked at Bob Lund. She had flown on that same space shuttle in previous years. Just before the disaster, Lund had been promoted to management after a career as an engineer. He knew the launch should be cancelled. The other three managers wanted him to agree with them that it was okay to undo the cancellation and “fly” as they put it. The data about cold and O-rings was inconclusive they pointed out to Bob Lund. He wasn’t fooled. He knew the launch should NOT proceed. He knew until he didn’t know.

Bob Lund acquiesed.

The four decent human beings who had committed murder without realizing what they were doing sat deathly silent with Dr. Ride and Richard Feynman and Neil Armstrong and the whole commission. The murderers wished they could change the past. As they examined what had happened, they came to know again. “You can’t prove the O-rings will fail . . .” is a true statement, true and powerless.

Reality doesn’t obey authority.

The more I think about irrationality among engineers, scientists, scholars, and in the legal system (and even in politics — don’t get me started) the more it seems helpful to divide reasoning into categories. I wound up with three: (1) social reasoning; (2) legal reasoning; (3) scientific reasoning.

Social reasoning tells us that the photographs of the spherical Earth from space and the videos of Neil Armstrong walking on the Moon are NOT the products of an omnipotent conspiracy that has deceived us about the nature of our planet and society. Social reasoning is based on a broad premise — the existence of a shared reality and its associated self-evident truths. We need not examine evidence when people make absurd claims that they themselves often do not believe. For a rock climber scaling El Capitan, each foothold and handhold must be solid: objective reality, like gravity, is not optional and some things really are inarguable.

Legal reasoning is often a matter of safety. We begin with a conservative premise that we do not abandon without hard, undeniable proof: the space shuttle is UNSAFE until we prove otherwise; the accused are INNOCENT until proven guilty. It’s a bit shocking sometimes how easily the burden of proof can get reversed. One minute an engineer is being questioned about every minute possible danger to the shuttle and the next he is being asked for hard proof to back up concerns about catastrophic O-ring failure, concerns that will be ignored unless he can come up with proof.

The shuttle exploded, as you know, because the burden of proof got reversed. It was as if someone held up an evil magic mirror to the usual process. The magic mirror of proof reversal combined with the cocaine of confirmation bias has had horrific results throughout human history. The shuttle exploded, people died. But that didn’t stop it from happening again in another place, in another context. And then again . . .

In 1992, Todd Willingham couldn’t prove he hadn’t killed his three children; therefore, he was guilty of purposely setting the fire that burned down his house and killed his children.

Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollecito were provably innocent but corrupt officials who had released a dangerous criminal five days before he committed murder were able to convict two innocent people to cover up their own incompetence and then, having fooled much of the public, had a grand time using a lovely young woman as a jailhouse showpiece for four years.

Willingham’s house burned down in an electrical fire. He was convicted of murder on the basis of “pour patterns” found by arson investigators. Tests for traces of flammable chemicals in the “pour patterns” were all negative. But the tests could have been wrong, theoretically.

Knox’s housemate in Italy was killed by a mentally ill habitual criminal who left his DNA inside the victim’s body and fled the country. He was identified by a handprint in the victim’s blood at the scene of the crime and was quickly caught by German police. Knox and her boyfriend, already arrested, were obviously innocent but were convicted in a trial that was Monty Python’s “burn the witch” skit in real life. People assumed, and the victim’s family still assumes, using social reasoning, that a judge would not participate in a bizarre farce.

In 2004, Willingham was injected with a deadly chemical. As the chemical moved toward his heart, Willingham used his last breath to tell the world he was innocent. “Pour patterns” are no more informative than Madame Trelawney’s tea leaves and are no longer accepted as evidence in U.S. courst. To this day, Todd Willingham’s own lawyer — assigned to him because he was too poor to pay for his own lawyer — thinks he was guilty, again using social reasoning.

When social reasoning and backwards legal reasoning are mixed into a toxic brew, dumped into courtrooms, and guzzled in the court of public opinion, there’s a name for the phenomenon: “miscarriage of justice.” We know all about it. In the U.S., an organization called “The Innocence Project” fights for rationality in courts.

But surely, you say, this irrationality doesn’t happen with brilliant scholars at our finest universities? How could it? After all, the job of scholars is to model rational discourse. Experts doing scientific tests helped us see for what it was the nightmarish nonsense called “arson investigation” that convicted Willingham and Italian scientists were instrumental in freeing Knox and Sollecito. They’re all pretty rational.

This means we can be sure scientists, experts, professors, and scholars are not susceptible to the kyptonite of a cherished premise. Right?

At this point the answer is predictable but I’ll say it anyway: Wrong. A new idea, if it is too new or too challenging or sounds funny or seems too simple or might be said by a child (“Look mom, Africa fits right into South America!”) might as well be a flat Earth or a faked Moonshot. Social reasoning and legal reasoning are routinely weaponized to fight the new idea with one goal in mind: kill it.

If Gerta Keller at Princeton thinks volcanic activity and not a meteor might possibly have killed the dinosaurs, she’s obviously just crazy because we know it was the meteor. The evil Dr. Keller is making wild accusations: the meteor theory is innocent until proved guilty; Keller doesn’t have absolute proof and must therefore be ignored.

Keller has been dealing with Kuhnian irrationality for decades. Her fellow scientists have not become physically violent, but that’s as good as it gets. At least she’s been able to publish, with difficulty.

If scientists were rational, if scientists always used the third type of reasoning, scientific reasoning, Keller’s theories, whether her fellow scientists agreed or not, would be accepted as worthwhile and even encouraged. Even if she’s wrong, the discussion is valuable. Even if all it does is strengthen the mainstream theory, that makes it worthwhile. And if she’s right, by God she has given us the gift of a breakthrough. Yes, it’s painful when it happens but it’s better than doctors continuing on and on forever believing that ulcers are caused by stomach acid.

Scientific reasoning is so powerful because it is based on an anti-premise: we don’t know. Those three words are harder to hang onto than one might suspect because we naturally get attached to our assumptions. We are all subject to confirmation bias. Keeping our heads clear requires a constant effort.

We refuse to rally around one answer. Instead, we make our best guess about the probability associated with each possibility: choice A might be 80% likely and choice B might be 20% likely. If choice B turns out to be true, we were not wrong. Remember, we said it choice B might be true: a twenty percent chance can easily happen. That’s the fun of scientific reasoning: you get to keep all possible outcomes; you might be better or worse at estimating probabilities but you are never wrong.

Scientific reasoning is the essence of openmindedness. Scientific reasoning lets us accept the changes that happen when some out-of-the-box thinker hands us a priceless gift, a breakthrough. Scientific reasoning is the antidote to dogma. Maybe all would-be scientists and scholars should be required to minor in scientific reasoning in college. Maybe then Gerta Keller wouldn’t have such a hard time.

Physicists are (usually) very good at scientific reasoning, maybe better at it as a group than any other group of scholars. It’s relativity and quantum mechanics that makes that happen. You have to drop pretty much all of your preconceived ideas about space and time, because, even though these ideas are quite useful in everyday life, they are bizarrely wrong at a fundamental level in ways physicists are still exploring. Physicists get trained in we don’t know early on.

Even so, physicists are perfectly capable of planting their faces in the snow as they ski down the mountain of scholarship.

Faster Than the Speed of Light tells the (true) story of mainstream physicists faced with an interesting new idea as the 20th century came to a close. You already know what happens in the story: mainstream physicists run away screaming but finally see reason. It’s a good story with a happy ending.

Read the book, but here’s the executive summary: physicists are comfortable believing that what they call “physical constants” such as the speed of light are truly constant. It is indeed simplest to assume that these constants have not changed in value at all since the universe began 13.7 billion years ago with a “big bang” — a term first used in a pejorative sense by people who, surprise, didn’t like the theory because it was a new idea.

Anyway, a faster speed of light in the very early universe seems like a strange idea at first but does seem to explain a lot about the way the universe looks today. If a full-fledged theory could be constructed and verified, knowing how a physical constant can change in value could ultimately open up a whole new level of inquiry in which we may someday learn how the physical constants are related to each other and even begin ponder the origin story of physics itself. In short, big stuff.

So it is an enormously interesting theory and you won’t be surprised at the mainstream’s reaction. “It cannot be so,” they said. “We are certain that the speed of light has been constant for all time. It is certainly true because you can’t prove it isn’t true.”

It was worse than they expected. The professional scientists trying to nurture their new idea knew their colleagues would be skeptical of a theory postulating a variable speed of light (VSL). The seasoned professionals didn’t think their colleagues would treat them like random people stumbling out of a bar spouting gibberish.

Fellow scientists dubbed the idea “very silly” (get it?). Scientific papers sent to leading physics journals were first blocked entirely and then held up for years. The blockade might have lasted decades if one of the proponents of the theory hadn’t been especially stubborn.

Today, VSL theory is socially acceptable to physicists and many professionals work on it without fear. It might ultimately be the greatest breakthrough of 21st-century physics. Or it might not. The good news is the attention VSL is getting means we will find out one way or another. The bad news is the mainstream did everything it could to strangle the new idea in its crib. New ideas aren’t like Hercules as a baby — they can be killed off before they have chance to fight back.

But how does one distinguish crackpot nonsense from interesting ideas? Must we accept all new ideas, even stupid ones, even crackpot nonsense? How did the person editing the journal Einstein sent his first relativity paper to know that he had damn well better publish that paper written by an unknown guy with a physics degree who couldn’t even get a real physics job and had to work in a patent office?

Einstein was making extraordinary claims about how the universe worked, claims that anyone, including the journal editor, would have to think were most likely wrong. The guy reading the paper, the journal editor, said later that he thought publishing the paper was his greatest gift to physics. Einstein started with known facts and laid out his idea clearly. The new idea might be wrong and probably is wrong, thought the journal editor. Then again, it might be a breakthrough. Of course Einstein’s work (he was far from famous at the time) should be published.

That was the special theory of relativity which predicted the speed limit of the universe later seen in particle accelerators. Fifteen years later, the general theory of relativity resolved the mystery of anomalies in mercury’s orbit: the sun bends space itself. Physicists were “agog” as the New York Times said at the time. This was not something humanity would have wanted to miss. Thank goodness for that editor.

The hard part isn’t so much recognizing evidence-based scientific reasoning, that part’s easy. The hard part is convincing yourself of three things: (1) premises, even long-standing ones, do not need to be protected and shielded as if they were small children; (2) all new ideas, including breakthroughs, look wrong or even sound absurd at first; and (3) smart people, including very large numbers of smart people, may be so unable to accept the loss of their premise that they speak and act hysterically.

Watching an irrational mainstream react to a new idea as it begins to look more and more likely to be correct is most illuminating. Their arguments become increasingly desperate. Circular reasoning rears its head and roars. Logic is twisted so horrifically, you need to look away. The “other side,” they say breathlessly, is motivated by malice. Weak arguments are pounced upon. Strong arguments are ignored. If there are no weak arguments, they are made up and then triumphantly pounced upon.

Kuhnian irrationality is easy to spot. The mainstream starts with its unshakeable premise and then immediately launches into a pointless debate. You can debate anything. Debating is wordplay. Debates are harmless fun but are ultimately meaningless. In a debate, the search for truth is left out in the cold.

Nevertheless, a deepset premise can take decades to uproot. Social reasoning or social reasoning combined with legal reasoning takes over and there’s nothing to be done. It may even take a few generations to put social reasoning aside, to walk past legal reasoning, to end the wordplay and to finally reclaim thought, humility, and evidence. Kuhn’s readers coined the term “paradigm shift” to label this arduous process.

We who love to tell ourselves stories about people living happily ever after tend to assume paradigm shifts always happen soon enough whenever they are needed. I wish to suggest here that this notion may be a fairy tale. I wish to suggest that there are paradigm shifts waiting to happen almost everywhere one looks.

In case after case, the situation looks the same: a small number of credentialed professionals have spent years or decades challenging a premise. The mainstream has reponded predictably with misplaced social reasoning and self-serving legal reasoning. The mainstream’s response (when they deign to respond at all) sometimes goes completely off the rails.

The Italian police, while Knox was in a jail cell awaiting trial, sprayed her bathroom with a chemical that would turn pink after a thirty minutes. They snapped a photo of the “bloody bathroom” Knox showered in while her roommate lay dead behind a locked door and released it to the press. The whole trial was like that. Knox did not need a defense. Even just looking at the prosecution’s case, it was obvious she and Sollecito were innocent. That’s what I mean here by “off the rails.”

You don’t have to be an Italian cop to do go off the rails.

Who Is the Most Irrational of Them All?

In the present work, we will tackle the most striking example of Kuhnian irrationality I know of. The example discussed here is in that late stage of development in which a mainstream with a perfectly plausible but deteriorating theory struggles to uphold an idea that is nowhere near as certain as legions of smart people once thought it was.

At this stage in the process, the mainstream slowly loses its battle to silence all discussion as more of its credentialed membership questions the once-unquestionable premise; serious discussion in journals seems imminent in this case though it has yet to occur. VSL spent about ten years in this stage; today, as you know, the constancy of the speed of light is a perfectly acceptable area of research.

The present example, because the battle has been raging for more than a century, offers us another crucible in which we can examine closely — in all its horrific detail — what Kuhn examined from a safe distance. Mainstream adherents of what I call the Shakespeare mythology — that we know with near-certainty who wrote the plays and poems — are still in a position to convince most people that social reasoning is the only appropriate way to respond to suggestions, incuding suggestions made by credentialed experts, that “William Shakespeare” was a pseudonym used by a member of the Elizabethan nobility and the businessman who was one of many William Shaksperes living at the time wasn’t even literate.

As was the case with VSL or continental drift or the extinction of the dinosaurs or the cause of ulcers, the consensus reached among most experts about what is likely to be true is perfectly reasonable but far from certain. The absolutely certain experts were embarrassingly wrong in the cases of continental drift and ulcers. However, in the cases of VSL and the K-T extinction and the Shakespeare mythology, it is still possible the mainstream will turn out to be correct. What all of these cases have in common is a wild exaggeration on the part of the mainstream of the certainty of their position and an unwillingness of mainstream professionals to accept uncertainty and seriously discuss the issue with their own colleagues.

Following the precepts of scientific reasoning, we will assume here that we don’t know who wrote Shakespeare. A businessman who lived in a town called Stratford a few days’ journey from London whose name was William Shakspere is a strong possibility for the man who wrote the plays which eventually had the “Shakespeare” byline appended to them. However, a reasonable person (i.e., you, dear reader) might not even say there is a 50% chance that the businessman was Shakespeare.

Imagine if it is really the case that most Shakespeare scholars regard as almost certain what might not even be as certain as a coin toss. That goes beyond overstating one’s case. That’s Kuhnian irrationality in spectacular relief.

To put the Shakespeare question in the tiniest nutshell possible for readers familiar with US government, imagine the following: an insider at the White House or someone with access to inside information creates dramatic work in which the president and the people around the president are portrayed as thinly disguised caricatures, often NOT charitably; no one openly takes credit for the work but publishers and cinematographers get their hands on it and produce it anyway; it is beautifully executed and becomes surprisingly popular; the name appended to the work is “Bob Wilson.”

A real person named Bob Wilson lived near Washington DC and was sometimes known to be in the capital city and was known to have friends and associates who were cinematographers. Years after Bob Wilson dies, the “Complete Works of Bob Wilson,” much of it never-before-published, appear in a magnificent volume and in that volume, two of Bob Wilson’s friends identify their friend Bob Wilson as the author Bob Wilson.

Posterity, obviously, can never be sure exactly what went on.

The basic facts of what happened in Elizabethan times are well known and mostly undisputed. A series of anonymous plays filled with inside knowledge about Queen Elizabeth’s court began to come out either in the 1580’s or in the early 1590’s. The plays became outrageously popular and, by 1598, had the “William Shakespeare” byline attached. Many of the questions we ask now were asked back then as well: Who was writing the plays? How did whoever it was know all that stuff about the Queen’s court? How did whoever it was get away with it? Why were all of the published plays bootlegs? Why were only half of the plays published at all? How did all the plays eventually come to be published?

The mainstream is 99.99% certain it has the answers to all of these questions. Their certainty has a tinge of the insane to it. The fill in gaps with what Mark Twain called “must have beens.” Challenges from credentialed experts, Nobel Prize winners, famous writers, Supreme Court Justices, or ordinary people are sniffed at as unworthy of serious consideration. The journals are “walled off” from any discussion of the matter.

There was a William Shakspere living at about the right time in a town called Stratford. His life created many documents, all of which are business-related. There’s nothing about writing. However, evidence from after he died strongly points to this man as the author. The reason I referred to this as “mythology” is not so much that it can’t be true — the posthumous evidence cannot be ignored — but is due to the fact that the evidence from Shakspere’s lifetime points so strongly to illiteracy: no books, letters, or manuscripts belonging to Shakspere have ever been found and no one who knew him knew him as a writer. On legal documents requiring a signature, clerks signed his name for him. So we don’t even know if he could write his name.

Mainstream scholars say Shakespeare must have been literate because he wrote his works. They say the lack of books, letters, and manuscirpts, and the absence of references to him as a writer during his lifetime by friends, familty, and colleagues is unfortunate but is merely bad luck. Sometimes they resort to the automatically true tautology, “Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare.” They say its odd that he didn’t sign legal documents but they regard the posthumous evidence as definitive and assume there must be some explanation for the not-signatures.

Heretical scholars call the businessman from Stratford “Shakspere” since that’s the name that appears on his birth and death records. The rebels say Shakspere not only appears to have been unable to write his name but was actually unable to write his name. The rebels think it is more likely that Shakesepare was a pseudonym used by a member of the Elizabethan nobility. One of them even wrote a Ph.D. thesis about this possibility and was granted a degree by a well known university causing no end of consternation in the mainstream community who do not call the colleagues who disagree with them “rebels” or “heretics.” People who think Shakespeare was a pseudonym get called “anti-Shakespeareans.”

A man named James Shapiro is a professor at Columbia and wrote a book called Contested Will in which he examined the history of the Shakespeare question. He didn’t use the term “anti-Shakespearian” in that book. Instead, he bragged about the journals being “walled off” from colleagues who disagree with the premise that “Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare.” He questioned the competence of his colleagues (at a different university) who granted the Ph.D. He diplomatically called the student (now a professor) and people like me who think Shakspere may have been illiterate “unreasonable” which is as good a word as any. I prefer the word “insane” but the difference here is rhetorical rather than substantive.

I think Professor Shapiro and I can agree on one thing: one of us, the present author or the Columbia professor, is insane. It’s not that we are dangerously insane (as long as we stay away from space shuttles) but, at least when it comes to Shakespeare, either I need a straitjacket or the professor does.

You, dear reader, get to decide. Someone needs to be (metaphorically) wrapped in a straitjacket and placed in a padded cell. I hope it isn’t me but if it is I promise to go quietly. I must put aside my bias and provide you with the strongest possible argument that the businessman from Stratford wrote the plays while also presenting the pseudonym argument that I regard as even stronger. I believe I can not only do this but that the mainstream argument, as presented here, is stronger than what Shapiro provides. Shapiro, as a member of the mainstream, has had to paint himself into a corner: he must present certainty where no certainty exists and is therefore led to saying ridiculous things and weakening (and maybe even demolishing) his own argument.

Despite the mainstream’s insanity, there is an argument that Shakspere should be considered as a possible author despite apparent illiteracy. There is also an argument for a member of Queen Elizabeth’s court who was known as a playwright but who never published under his own name. It’s easy enough to present the whole story fairly despite personal biases when you don’t have to claim certainty. My task is immensely simplified by the existence of a body of facts disputed by neither of the two “sides.”

William Shakspere was a common name in those days and there were many of them who lived at about the right time. But it was the businesman from Stratford who was later identified as the author. This businessman left behind extensive documentation of his business activity: he was a well-known creditor in his home town with investments in agriculture, land, barns, stables, orchards, grain, malt, houses, and, notably, London’s leading acting company. His literate friends and neighbors and business associates wrote to each other about him and his money, but said nothing about him being the greatest writer in England until seven years after his death. At that time, in 1623, two of his London business associates explcitly identified their late friend as the great writer Shakespeare.

It is this identification that, not without reason, causes the mainstream feel confident that it is correct.

So the posthumous identification is solid evidence. But there’s a problem. If this identification is not valid, if the project undertaken seven years after Shakspere’s death was designed to conceal the true author’s identity, the mainstream theory is weakened, probably fatally. Shakspere’s biography is, even mainstreamers readily admit, extremely odd if he was the greatest writer in England. So it’s hard to overstate the importance of the one piece of evidence that identifies him a writer named Shakespeare as opposed to an illiterate businessman named Shakspere.

I think a good argument can be made that the identification seven years after death is like the secondary O-ring in the space shuttle: absoutely critical, a sine qua non of the mainstream’s theory. Certainly no one would claim the posthumous evidence is not extremely important.

In addition to the concerns about Shakspere’s biography and the importance of a single piece of evidence, there is someone other than Shakspere whose biography has been examined closely starting about one hundred years ago. Although many possible “Shakespeares” have been suggested over the years, this particular candidate’s biography seems ideally suited to make him a plausible Shakespeare. It is fair to say a consensus among rebellious experts has formed around this person. We will assume for the purposes of the present work that one of these men wrote the works of Shakespeare and we will assume that we don’t know which one it was.

The lack of a definitive answer is of course necessary if we are going to engage in what I call scientific reasoning. Our goal is to reach a point where a reasonable person can assign rough probabilities to the two possibilities. If you think there is a 99.99% chance that Shakspere was the author then you agree with the mainstream. If you think Shakspere is 50-50 or not even 50-50 then you agree with me that the mainstream has driven itself to insanity when it comes to this particular issue.

The 99.99% certain mainstream has a lot of problems, none quite so bad as the lack of a signature. William Shakspere “signed” his name five times on documents that have survived. But each “signature” was written by a different person. The mainstream discovered this, NOT the rebels. No other Elizabethan writer had people signing important documents in their stead.

Writers and literate people in general of that time period left behind identifiable signatures that made their literacy clear: there are hundreds of examples. The lack of a signature in Shakspere’s case might not be such a problem if not for the rest of his biography. We have title pages that say “Shakespeare” on them and we have a man with the right name who was identified as the author after he died. But we have nothing from his lifetime to show that he was literate or thought of as a writer.

Ben Jonson, the second-most-famous Elizabethan writer, could write his name and was known as a writer. Jonson left behind books, letters, and manuscripts. No one would ever say, “We know a man named Ben Jonson who lived in London in 1600 was literate because the name Ben Jonson is on a large number of printed title pages.” But Shapiro regards the title pages that say “Shakespeare” as “overwhelming evidence.” He weakens his argument with statements like this.

Ben Jonson’s biographers do not regard title pages as “overwhelming evidence.” Instead, they spend years looking at the books, letters, manuscripts, court appearances regarding written works, payments for written works, jail time for writing the wrong thing, and eulogies praising him as a writer. This man’s name was Ben Jonson and he was the writer Ben Jonson while he lived. Ben Jonson biographers rarely rely on posthumous testimony about Jonson’s life. And a Ben Jonson biographer would be no more likely to rely upon title pages to prove literacy than he would be to strip naked while cold sober in the middle of a formal dinner party and start dancing on the table saying “Jonson wrote Jonson.”

Title pages and tautologies aside, Shakspere did have a connection to the theater and this does mean something. The problem is Shakspere was a shareholder, a part-owner of London’s leading acting company, but was not documented as a writer for that acting company or for any of the other acting companies that put on Shakespeare plays.

Shakspere also invested in agricuture but was not a farmer. He invested in grain but was not a brewer. He invested in real estate but was not a builder. Most playwrights weren’t involved in the business of putting on plays. In fact, if Shakspere was both an author and a shareholder, he was the only one of that era. Still, being a playwright doesn’t stop a person from being involved in the entertainment business. Moliere, centuries later, is an example of someone who did both. So it is possible Shakspere was a businessman-writer.

Thoughtful people who look at Shakspere’s life and who begin to wonder if the possbility that he wrote the plays is really enough to put it beyond question usually do so only after reading one of the classic biographies. That was the case with Diana Price who has become the Elaine Morgan of the authorship question.

Price read the classic Schoenbaum biography and that was the beginning of the end of her belief in the traditional story. Then she read all of the mainstream research or a lot of it anyway and it only got worse. She decided to write a book since the experts didn’t seem willing to confront the problem they had discovered. She was among the first or perhaps the first to use comparative biography to make the Shakspere problem crystal clear in a book-length work. She wrote the groundbreaking Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography.

In her book, published by an academic press, Price points out that by the standards of the biographical information available for other Elizabethan authors, Shakspere’s biography as a writer is far-fetched at best and astronomically improbable at worst.

I’m going to end this section with a macabre question: if you had no other choice, if you had to stake your life on Shakspere being the author OR on a coin flip, which would you choose? The shuttle astronauts, had they had the corresponding choice (Thiokol experts or coin flip) would have picked the coin flip — the engineers’ concerns, stated openly at the time, were that serious. In this case, would you pick the mainstream’s claimed 99.99% certainty or a coin flip?

You can’t answer yet because you don’t know enough. But I will ask you again.

Monstrous Popularity, a Virtual Particle, and a Bad-boy Earl

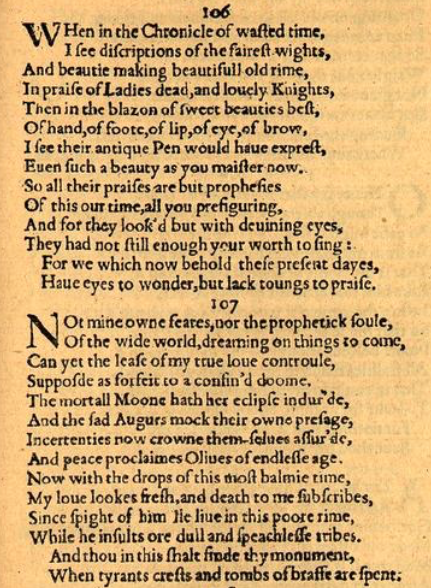

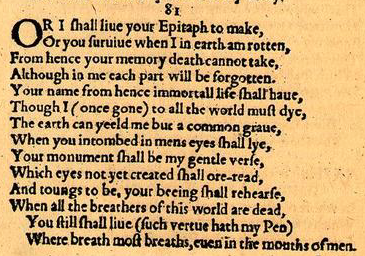

Queen Elizabeth loved Shakespeare. King James loved Shakespeare. One thing we know about Shakespeare is that the written word was his life. In his Sonnets he wrote to his beloved and to posterity, to us, of his life as a writer: The worth of that is that which it contains, And that is this and this with thee remains.

But it started with the plays. During Queen Elizabeth’s reign, a series of remarkable plays came out properly described by one or two or all three of the following characterizations: (1) a brilliantly written reimagining of an old classic; (2) an extremely useful piece of pro-protestant, pro-monarchy propaganda; and/or (3) a juicy delight full of inside dirt from the Queen’s court including gentle pokes at the Queen herself and not-so-gentle pokes at her courtiers.

The Queen, always happy playing her courtiers one against the other and no stranger to the value of controlling the media, had lots of reasons to support the plays. In fact, she put her top spymaster, Walsingham, in charge of the Queen’s Men acting company so that he could do what he did best — watch over and protect her realm manipulating the public always to the benefit of the powerful.

Someone was dishing courtly dirt and getting away with it and the Queen liked it enough that she put big players in the game and perhaps even rewarded the dirt-disher.

Needless to say, the plays became ridculously, outrageously, almost unbelievably popular. In terms of sheer poplularity, Shakespeare far outstripped all other Elizabethan playwrights put together. Nothing like it had been seen before. And such utter literary dominance hasn’t happened since. I suppose if Meghan Markle and Prince Harry posed for Penthouse, we might see something like the fuss that Shakespeare plays enjoyed, but short of that, I would argue that Shakespeare’s popularity as a playwright was unique to history.

That the playwright wasn’t available was a problem for publishers who desperately wanted the plays in print. Would-be publishers were forced to work off what scripts they could get their hands on or even sit in the theater copying down lines. The results were substandard: missing scenes, misnamed characters, and garbled speeches were the norm for Shakespeare plays published while the author was alive.

As far as anyone knows, all Shakespeare plays published during Elizabeth’s reign were either entirely unauthorized or published with essentially no help from the author. Mainstream biographers who would never in a million years suggest that they had the wrong man nevertheless scratch their heads about the missing author.

Bootlegging happened certainly but no other Elizabethan playwright was 100% bootlegged. It is, everyone admits, a bit strange. The light touch, to put it mildly, of Shakespeare-as-author next to the hammer blow, to put it bluntly, of Shakspere-as-businessman is impossible to explain though not impossible to comment on.

The late great Harold Bloom wondered how any artist could regard the final form of King Lear as “a careless or throwaway matter.” Bloom didn’t claim to know what was going on four hundred years ago; he settled for entertaining himself and his readers by waxing poetic about genius-Gods like Shakespeare casting their stars to the floor.

Bloom was smart to avoid trying to actually answer the central mystery of Shakespeare’s biography — where are the footprints of the greatest writer in England? — but even Bloom couldn’t help going on a bit about the oddness of it all. He writes of a mysterious “inverse ratio.” It is “beyond our analytical ability” he says.

Bloom’s inverse ratio is a comparison of the “virtual colorlessness” of the well-known businessman on one hand and the “preternatural dramatic powers” of a writer with more heart than Bloom could easily imagine fitting into one person on the other hand. For Bloom to say it is beyond his analytical ability is a big deal — Bloom had no shortage of analytical ability.

Bloom’s vision of “virtual colorlessness” paints a perfect picture if you happen to be a physicist: virtual particles in quantum mechanics exist in a mathematical sense but not in a literal sense. A virtual particle is and yet is not. So Bloom’s words are, as always, especially apt.

Park Honan captured the same idea and he might even claim to have done so more pithily than even Bloom did. Park Honan, who wrote a full-length biography of the man he thought was the author, encapsulates his subject’s life with fine rhetorical economy: “Shakespeare,” he says, “seems to have fluorished with a certain annihilation of the sense of himself.”

I added italics to emphasize Honan’s Bloom-like vision of a great author who regularly visited the business world and then somehow disappeared to visit the literary world, annihilating himself at will just like the Cheshire Cat in Charles Dodgson’s (Lewis Carroll’s) classic fantasy.

The brilliant and thorough Samuel Schoenbaum, a more prosaic observer than either Bloom or Honan, ran into the same problem they did. Schoenbaum, writing the classic Shakespeare biography, finds that he must write of an author who had many friends and associates who wrote to each other about the local businessman Shakspere, but said nothing useful.

Letters back and forth amongst Shakspere’s associates indicate that people in Stratford didn’t know or care about their “townsman” being the greatest writer in all England. It must be, Schoenbaum speculates, that they were more interested in the business side of things. “They probably troubled their heads little enough about the plays and poems,” Schoenbaum guesses.

So we don’t need Alice and we don’t need the quantum. People who knew personally “the admired poet of love’s languishment” also apparently knew even better who buttered their bread. “Business was another matter,” Schoenbaum reasons. “They saw Shakespeare as a man shrewd in practical affairs,” he concludes.

E. A. J. Honigmann went straight at the business-versus-writing issue. He researched Shakspere’s business activities thoroughly: “If one lists all of these various activities in chronological order,” Honigmann says, “one wonders how the dramatist found time to go on writing plays.”

Honigmann didn’t imagine for a microsecond that the businessman might not be the author. He was just pointing out the difficulty of holding down two full-time jobs.

Bloom, Honan, Schoenbaum, and Honigmann and other mainstream biographers were and are under the spell of a simple premise: we know with virtual certainty who wrote the plays. They would be unable to question it no matter what the evidence was because if the premise a wrong a LOT of time has been wasted.

Mainstream biographers are to be pitied like Shakespeare’s Titania who loved Bottom unquestioningly.

And yet these biographers are game as they proceed bravely forward with nothing to go on: no letters written or received, no books owned, no manuscripts found in his house, and no references by friends, family, or business associates to Shakspere as a writer until he had been dead seven years. If only they could let go of the conceit of certainty, they might wonder if someone else could possibly have written the plays.

If, indeed, we permit uncertainty, we can accept Shakspere’s biography as it stands and consider therefore a possible author who was (we thank our lucky stars) certainly literate. A prodigy from an early age he was, a member of the Queen’s court as an adult, known publicly and privately as the greatest of the courtly playwrights, praised to the skies during and after his eventful life, he was the ultimate insider-author and he was also a man who never published a play under his own name.

Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford had dozens of books dedicated to him and received florid praise from professional writers such as Harvey: “I have seen many Latin verses of thine, yea, even more English verses are extant; thou has drunk deep doughts not only of the Muses of France and Italy, but has learned the manners of many men and the arts of foreign countries.”

After his death, Oxford was worshipped on the same page as other ever-living literary giants of the Elizabethan era like Edmund Spenser and Samuel Daniel. In one book appearing and reappeaing in multiple editions, Oxford was listed first; other great authors were listed after him; “Shakespeare” wasn’t even mentioned. Other books mentioned Shakespeare but not Oxford. Still others mentioned both. Of course, just as there’s no accounting for taste, there’s no knowing who knew what when.

Oxford, though good with words, was not a good boy. He was known as “fickle” and irresponsible, not good for anything but writing. The Queen repeatedly refused to grant him positions of responsibility within her realm despite his repeated requests. Nevertheless she set him up for life in June of 1586.

The spymaster, Walsingham, as you know, was at that time running the Queen’s Men. He was executing what was called “the policy of plays,” using the acting company for state-sanctioned entertainment. A letter to Walsingham from Lord Burghley written in June of 1586 discusses Oxford and the Queen and something momentous that the Queen is about to make happen that will change Oxford’s financial situation forever. Nothing is said about exactly what was going to happen. Burghley wanted Walsingham to let him know in the event the Queen informs Walsingham of a final decision.

At the same time, Oxford was busily writing a letter to Burghley asking for a familiar favor — a loan of 200 pounds (a large sum). Oxford assured Burghley he would be able to pay him back as soon as the Queen “fulfills her promise.”

Something was about to go down.

And so it did. That week in June of 1586 Oxford was officially granted an extraordinary lifetime stipend by the Queen. I’m no Shakespeare so I’m having trouble finding the right word here: “extraordinary” doesn’t quite capture it. So bear with me if you will.

The life of the literary earl was changed at a stroke. The man who sold his lands to fund his revelry and his travel, the irresponsible worshipper of the written word, the man who never could get his hands on enough money to live his life to the fullest and beyond was now guaranteed 1000 pounds per year forever for doing we know not what. For the amount was spelled out in the written record but Oxford’s end of the bargain was not.

The gargantuan sum was more even than Lord Burghley himself — the Queen’s right-hand man and the most powerful man in England — was paid. Instantly, the “fickle” Oxford who did nothing right (except write) became the best-compensated member of Elizabeth’s government. He would never be as rich as Burghley who had plenty of non-salary income on top of the payments out of the royal treasury, but the Queen’s largesse made Oxford rich beyond the dreams of (ordinary) avarice though clearly not beyond the great Earl’s ability to spend every pound that came his way.

If, indeed, you weren’t an insatiable earl, you could live on a few pounds a year. Fifty pounds a year was a great salary for a senior official. Burghley got 800 pounds a year as Lord High Treasurer. Only King James VI of Scotland, the recipient of 4000 pounds per year, drew more gold out of the treasury than the man who this same King James, now King Jame I of England, called “great Oxford.”

Great Oxford didn’t have a country to run. In fact, the award stipulated that he could spend his 1000 pounds per year however he wished. Only one thing is certain about the award: the Queen NEVER handed out money without gettting something in return.

This hasn’t stopped at least one mainstreamer, evidently terrified of Oxford, from suggesting that Queen Elizabeth paid Oxford 1000 pounds a year in exchange for his good behavior! Though it is hard to imagine a more fatuous argument Oxford did make name for himself with his rash behavior.

In 1581, the literary playboy slept with one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting and got her pregnant. The Queen’s ladies, needless to say, were not on offer to her male courtiers. The lustful earl spent some time in the Tower contemplating his sins. His mistress and her baby were locked up as well with mother and child in different quarters from Oxford. Meanwhile, the Queen cooled off.

After the couple and Oxford’s bastard child were released, Oxford’s retinue and that of the irresistible Anne Vavasour met on the streets of London to do battle. (Of course they did, what else would happen at this point in the story?) History tells us that sword met sword and that blood was spilled. At least one person died as the battles flared repeatedly. Oxford himself was injured.

That was then. By 1586, the brilliant and cocksure earl had become a paid luminary in Elizabeth’s realm. He could continue to pay his long-time literary secretaries, the writers John Lyly and Anthony Munday and he would work with them as the 1580’s ended and the 1590’s began. The three men, along with other writers in their circle, went to town as it were during those early years vowing to one another that literature would never be the same.

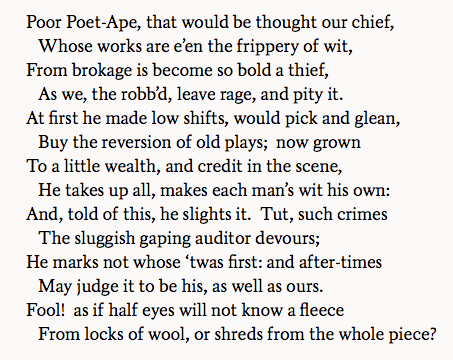

Lyly, Munday, and other writers such as Robert Greene and George Peele produced an avalanche of original work, dedicated some of it to Oxford, and did indeed remake the Elizabethan literary scene. The dedications and the praise were all the credit Oxford received unless you count the 1000 pounds a year which, IF it was being paid to him for writing, pretty much makes him Shakespeare.

Many of the plays that came out in the 1580’s did not have Lyly’s or Munday’s or Greene’s or Peele’s byline on them; instead, they were anonymous. In fact, anonymous work very similar to what were later officially Shakespeare plays began appearing. Four important Shakesepare precursors were King John, King Leir, Henry V, and Richard III with longish titles spelled and worded only a little differently from the eventual Shakespeare plays and plots and dialog so similar it is assumed that Shakspere, after arriving in London from Stratford, must have used these plays to create his own.

IF, instead, these four plays were first drafts of Shakespeare plays, written long before Shakspere got himself to London, then Oxford could step up to the podium and declare himself Shakespeare and we would have to agree.

Shakspere was certainly in London in the early 1590’s and in 1594, a play called Titus Andronicus appeared in print with no byline. Titus Andronicus is thought to be the first Shakespeare play to be published. In 1598, with Shakspere appearing now and then in London, Love’s Labours Lost appeared in print as the first play with the Shakespeare byline.

Of course, Shakespeare was already a household name by then because the byline appeared on two epic poems published WITH help from the author — they were the only Shakespearean author-publisher collaborations but the publishers left us nothing about their experience with the actual author who for all we know was Shakspere or Oxford or someone else. The epic poems were published in 1593 and 1594 and the Shakespeare byline, whoever was behind it, knew instant fame.

A Shakespearean Tragedy in 2020

The stipend handed to Oxford by the Queen proves nothing. But the mainstream is so worried about it that one of them was willing to go on record claiming Queen Elizabeth I could be bent to the will of a wanton courtier and made to part with gigantic amounts of money! Someone’s torn right through his bathing suit. Obviously, the woman who eventually became the most celebrated monarch in English history wouldn’t have lasted five minutes as Queen if she was as weak as this mainstreamer suggests. The mainstream, when it comes to the most difficult points in the Shakespeare story, seems willing to embrace gibberish even when they don’t need to. Again, the stipend proves nothing.

But there are a couple more facts to add before we have a good sketch of Oxford as a possible Shakespeare. An English English Professor, R. W. Bond, active circa 1900 collected John Lyly’s works in a three volume set and wrote this of his subject: “There is no play before Lyly.” Of Lyly and Shakespeare he wrote this: “In comedy, Lyly is Shakespeare’s only model.” Bond thought Lyly was more influential on Shakespeare than any other writer.

Oxford’s biography was not well known when Bond was working so Bond didn’t know that Oxford had hired Lyly and he didn’t know that Oxford was frequently listed as the greatest of the courtly playwrights. Today, we take the level of information and research available to everyone for granted, but Bond didn’t have all the facts in the world at his fingertips the way modern scholars do.

Of course, we can see that Shakespeare and Lyly may well have been influencing one another all through the 1580’s and it is certainly a matter of interest that Oxford’s secretary, Lyly, happened to be the Elizabethan writer most closely tied to Shakespeare. Bond isn’t alone in his opinion either: “Drawing on Ovid [Shakespeare’s favorite classic poet] and Plutarch and emphasizing a beauty of style, his [Lyly’s] works suggested more dramatic possibilities to Shakespeare those of any other comic playwright.” That’s a Park “Cheshire Cat” Honan quote.

So Shakespeare certainly knew of and appreciated Lyly’s works and, if he was Oxford, knew Lyly personally and worked with him directly. Also in the department of who did Shakespeare know? is the writer of the only surviving Shakespeare manuscript. Although no manuscripts or handwritten works of any kind belonging to Shakspere were found after he died, there is a handwritten play part of which is, everyone agrees, authentic Shakespeare found amonst the papers of an Elizabethan writer with whom Shakespeare evidently worked. This writer is NOT John Lyly.

The play is Sir Thomas More and the original manuscript plus an edited version both survive. The edited version includes a number of different handwritten pieces by a number of different people. Not all of the pieces can be identified; some may be written by unknown scribes. Some mainstreamers, embarrassing themselves in a truly horrible way, say that the handwriting in the five different Shakspere “signatures” can be matched to the handwriting on part of the Sir Thomas More manuscript. This argument is NOT embarrassing like a torn bathingsuit; we’re in the realm of public masturbation here. The reader may wish to quickly recall that the fact of the multiple people signing documents for Shakspere can be found in the work of Schoenbaum himself, perhaps the best-known mainstream biographer, and then as quickly as possible forget that a number of mainstreamers spew such nonsense as part of Sir Thomas More being in Shakspere’s nonexistent handwriting.

Anyway, the handwriting on the primary manuscript has been identified. It is, you will not be surprised to hear, in Anthony Munday’s hand. No one thinks Munday or Lyly was Shakespeare: they both published plenty of their own non-Shakespearean work. Sir Thomas More was never published though the manuscript and the edits tell quite story: Munday wrote a play and Shakespeare and a number of other writers worked on it.

So the most famous of the Elizabethan courtly playwrights hires Shakespeare’s biggest contemporaneous influence (Lyly) and also hires the man (Munday) responsible for the only Shakespearean manuscript so far found. And he was getting 1000 pounds a year from the Queen for God-knows-what. Given these very basic (and inarguable) facts, it isn’t hard to understand why a reputable institution like the University of Massachusetts at Amherst would allow Roger Stritmatter to write his dissertation on evidence for Oxford’s authorship of the Shakespeare canon. UMass Amherst, to the horror of a frozen mainstream, granted Dr. Stritmatter his Ph.D. in 2001.

Mainstreamers don’t have kind words for their colleagues on Stritmatter’s dissertation committee — in fact, they routinely imply that incompetence caused said colleagues to improperly grant Stritmatter a Ph.D. I would say it’s hard to imagine anything so graceless as a one professor telling another he doesn’t deserve his Ph.D., but it is November 2020 as I write and people who matter to me are dying while a graceless leader pretends the election is fake news so it isn’t so hard to imagine, unfortunately.

It’s tragic in other ways too if Oxford really did write the plays. Sir Derek Jacobi has said one cannot understand Shakespeare without knowing Oxford’s biography. If that’s true, I often wonder, then what of Harold Bloom? If scene after scene in play after play takes its cue from Oxford’s life then what can we say for Bloom, who loved Shakespeare, who graced us with his brilliance, who knew the scenes and speeches and characters by heart and who died possibly missing out on knowledge of the true author simply because mainstream scholars, our truth seekers, the people we depend on for enlightenment refused to even discuss it. Bloom was a brilliant man who I think was open-minded though he dismissed the authorship question; I believe if his colleagues had allowed work to be done on Oxford and if that work was sound, Bloom might have been convinced before he died.

RIP Harold Bloom 1930 – 2019.

The First Folio Strikes Back

There’s nothing wrong with intelligent skepticism about Oxford. After all, nothing directly naming Oxford as the author has ever appeared. He died in 1604 without a will and without eulogies. A play that he wrote about a “mean gentlemen rising at court” (possibly Twelfth Night) that existed in manuscipt into the 1700’s has been lost. So the Stritmatters and Jacobis of the world who sometimes seem pretty sure of themselves (and perhaps have a right to be) don’t have blatantly obvious proof. If they have less obvious proof (and they may have) we ordinary people can’t say whether or not they have a right to their confidence because the full discussion in peer-reviewed journals we would need to make such a determination isn’t happening.

We’re stuck with the same old problem: we don’t know. For all we know, even though Oxford, what with his family sword battles over his love affair, is a compelling candidate, Shakspere may have written the plays after all. Remember, he was identified as the author seven years after his death. And it’s a pretty good identification.

The businessman named Shakspere died in his hometown of Stratford in 1616. There are no surviving eulogies but a three-page will written in broken legalese (far below the legal ability of the expert who wrote Shakespeare’s plays with their clever use of fancy legal concepts) does survive. Someone in Stratford took down the will for Shakspere bequeathing his lands, stables, barns, orchards, houses, and cash to his two illiterate daughters (Judith signed her name with a mark; Susanna held her husband’s medical journal in her hands but told the person buying it she didn’t know what it was).

The will which goes on and on for three pages but never mentions a book or a manuscript or education or a map or a musical instrument or even an inkwell is explained by the mainstream by comparing wills of other writers that were equally boring if not equally lengthy. The absence of eulogies has been explained as follows: Shakespeare was mostly a playwright as opposed to a poet and, even though he was more famous than all other writers put together, he didn’t get eulogies because playwrights were held in lower esteem than poets. Some mainstreamers have noted the absence of eulogies for Shakspere and explained this by noting that he was mostly thought of as a playwright and playwrights didn’t get the same treatment when they died as pure poets.

Like most of the excuses made for Shakspere’s all business birth-to-death biography, the will excuse and the eulogy excuse arent’ especially good or especially bad. We are, as always, left with the fact that the businessman seems to have been just a businessman who perhaps didn’t have time for his daughters because he was so busy and didn’t see to it that they learned to read because they were country girls. It’s all plausible if not especially satisfying.

But then a miracle happend. Seven years after the apparent businessman died, in 1623, half of Shakespeare’s plays existed in print with varying levels of accuracy. That year, thirty-six manuscripts materialized like the flame of the lord on Mount Sinai.

Macbeth, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, Taming of the Shrew, A Comedy of Errors, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and Cleopatra, The Winter’s Tale, and other masterpieces would now be published for the first time. Bootlegged plays like Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, King Lear, Richard III, King John, Henry V, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, The Merchant of Venice, The Winter’s Tale, and all the others would now be published properly.

Someone had the manuscipts. Someone actually held in their hands a stack of the handwritten priceless documents. Perhaps they didn’t know how much posterity would treasure them. Perhaps whoever it was had other things on their mind. But the fact is, all of Shakespeare’s works in his handwriting had been in someone’s possession, saved en masse for three decades or more.

This miracle is known to us as the First Folio — Shakespeare as we know Shakespeare. The First Folio was published under the auspicies of the Earl of Montgomery and his brother, the Earl of Pembroke. These are the famous “incomparable pair of brethren” to whom the First Folio is dedicated. They had the plays and arranged for their publication. But where did they get them?