Paradigm Drift: The Structure of Scientific Delusion

Preface

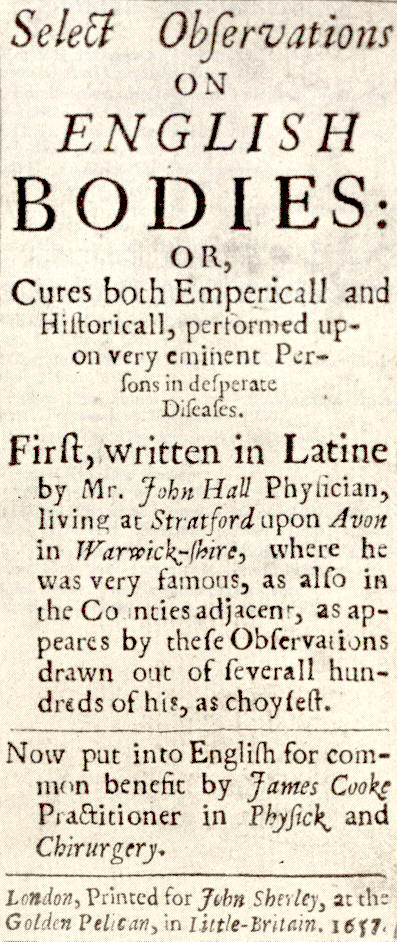

Thomas Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, tells of unexpected discoveries and dramatic “paradigm shifts” — metaphorical earthquakes in which the common ground “shifts” beneath scientists’ feet. The more shocking, the more impossible, the discovery, the more likely it is to someday be seen as the harbinger of a “scientific revolution” — a whole new world created over decades by scientists who adopt the new paradigm.

That’s one side of the scientific coin. The other side, the side we’re going to talk about, isn’t quite so glorious. Scientists must occasionally contend with popular guesses masquerading as paradigms. The scientist knows the guess is wrong, knows the prevailing paradigm is in no danger of being shifted, offers a much better guess that might even be correct, but has a Hell of a time convincing colleagues to let go of a theory that never earned the title.

The scientist’s colleagues call the guess a theory, treat it like a paradigm, and make every effort to blockade the rebel in their midst. Evidence eventually prevails: a guess originally made with little or no evidence is quietly abandoned. There’s no revolution.

It’s embarrassing. Then again, it may not be embarrassing. If we’re lucky, it’s embarrassing.

This is, first, a book of stories, stories of embarrassment past and embarrassment yet to come. This is, second, a book of language, the language of irrational certainty. Finally, this is, third, a book of scenarios supported only by their own internal logic, scenarios confidently asserted, scenarios leading to disaster and death.

Glossary of Terms

Kuhnian paradigm: foundational understanding that serves as the basis of all research; common ground.

paradigm shift: a drastic change in the fundamental assumptions underlying a field; the impossible come true.

Kuhnian resistance: defense of the current paradigm based on a belief that its problems can be fixed; doubt about the need for a whole new world.

scientific revolution: the embrace of previously unimaginable concepts; a new world.

false paradigm: a widely accepted guess or theory backed by limited evidence but treated like a paradigm; fashion.

paradigm drift: the tendency of the establishment to settle on one possible theory among many; groupthink.

gratuitous resistance: the blockading of credentialed experts who question a popular guess or reject a fashion, preference, or tradition; censorship.

scientific delusion: the rejection of evidence-based reasoning; irrational certainty.

Introduction

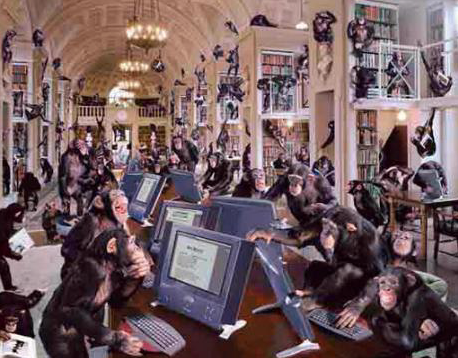

Franz de Waal is a primatologist following in the footsteps of Jane Goodall. Both researchers have commented on a bewildering phenomenon faced by scientists who work with minimal preconceptions.

Dr. Goodall named the chimpanzees she was studying and noted that they had distinct personalities. This, surprisingly to her, was a big problem. Her fellow scientists didn’t like her approach. Animals didn’t have personalities. And one shouldn’t name them. They objected “most unpleasantly,” Goodall says. ”I didn’t care; I didn’t want to be a professor.”

To this day, Goodall finds the certainty evinced by her colleagues in the 1960’s bewildering: “Anyone who has ever owned a dog knows animals have personalities,” she says. She had volumes of evidence, but evidence didn’t seem to mean much to many of Goodall’s peers.

A generation later, de Waal says that in his field it is still often the case that “authority outweighs evidence.” His peers, he says, regularly “cling to unsupported paradigms.” In other words, they are absolutely sure of this or that preconceived notion even without supporting evidence. I prefer the term “false paradigm” to refer to guesses that one is not allowed to contradict. But de Waal gets priority for pointing out the irony of “paradigms” that are anything but.

De Waal has had experiences in which colleagues won’t even discuss the possibility that their guess might be wrong. De Waal doesn’t make strong claims in his research — he makes observations about social behaviors in his furry subjects that parallel familiar social behaviors of not-so-furry primates who read early drafts of books and swim across lakes. Some scientists, unhappy about the revealed similarities between humans and other primates, once upon a time found it hard to accept that chimpanzees can reconcile after a conflict. Dr. de Waal offered to show them, but they refused to look.

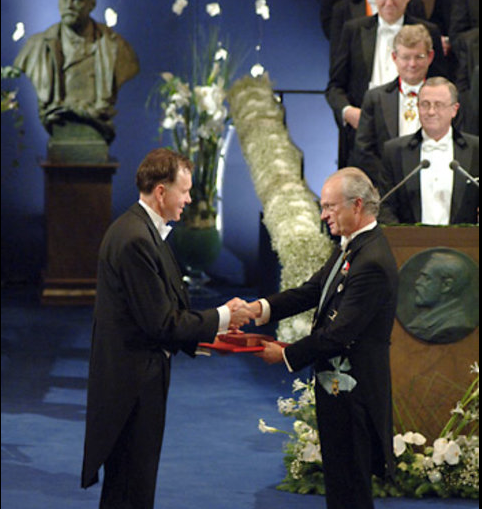

Primatologists are not the only scientists running into false paradigms. Physicist John Clauser couldn’t get a job because he was studying physics regarded by his peers as unfashionable. His work got called “junk science.” I remember reading his paper as a young physicist: it was a brilliant elucidation of one of the most surprising consequences of quantum theory. So why was he treated as if he said aliens landed in his backyard and turned water into fossil fuel? In the 1970’s, it was fashionable to “not worry” about quantum theory: “it works; no need to study it.” In 2022, John Clauser became a Nobel laureate.

Joao Magueijo is a cosmologist who studies the origin of the universe — the Big Bang. He’s fully on board with the basic theory, but found himself blockaded by peers because he had an idea that would slightly alter the theory. He said some of his colleagues behaved like “rabid dogs” in their efforts to stop him. His idea is now a vibrant sub-field within cosmology, but it took years for Joao to get a speculative idea published in an inherently speculative field.

James Watson also encountered resistance. Genes, chromosomes, and DNA were already well established as crucial elements of the genetics paradigm. Watson, Crick, Franklin, and Wilkins knew the next step was to get the precise structure of DNA. It was February 1953 when a three-dimensional model that looked like a toy finally sat on Crick’s desk. It was the biggest advance since Mendel created the genetics paradigm; the Nobel Prize was a lock. The boss who had told Watson to work on something else (!) had to admit the younger biologist had good instincts.

Watson wrote that to get his work done, he had to navigate a minefield of what he called “stifled academics.” Watson’s boss didn’t think much of model-building so the young biologist had to work in secret. The paint-by-numbers scientific culture felt to Watson like a ball and chain. He wrote of his gradual realization that many of his scientist peers were “narrow-minded and dull.”

Barry Marshall not only did some of his work in secret, he continued to be blockaded even after he made his breakthrough. Marshall didn’t discover bacteria; he wasn’t trying convince colleagues of the importance of hand-washing; he did not develop antibiotics. All of that was part of an already-established paradigm. All Marshall did was wonder if maybe the idea that bacteria couldn’t survive in the stomach was wrong.

This is science. It’s got to be accepted. That’s what he thought as his colleagues looked askance at the news that virtually all of them had been operating under a false assumption. Bacteria could indeed survive in the stomach and did cause ulcers and these ulcers were curable. For years, Marshall cured as many ulcer patients as he could while his colleagues slowly let go of a guess that had, with disastrous consequences, come to be treated as a paradigm.

During those years of narrow-mindedness, many people, including my great uncle, died of a curable disease — severe ulcers end in stomach cancer. Marshall won a Nobel prize in 2005 not for any revolution that changed the way science was done but simply for wondering if a guess might be wrong and following through.

Mathematician Eugenia Cheng laments the fact that publication in her field seems to be more about “gatekeeping” and “exclusivity” than communication. Cheng has the temerity to question this and other social norms. She regards projected confidence (aka bluster) as selected for by our educational system and points out that being uncertain and questioning one’s assumptions makes for better science than loud claims that one has everything in hand. Reading Cheng’s book, X+Y, one gets the feeling that our social norms are impeding progress, that something is rotten in the state of Denmark.

In this book, I hope to build upon what Cheng and the other scientists have revealed and make the case that the resistance to progress felt by primatologists, physicists, biologists, mathematicians, and experts in a variety of fields is not always an exercise of reasonable caution. I realize of course that in some circumstances, resistance is unavoidable. Thomas Kuhn, in his famous book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, argued that resistance to revolution was inevitable, reasonable, and even useful. I don’t disagree.

There is a crucial distinction to be made here. Kuhn was talking about scientists resisting wholesale changes in the most basic assumptions underlying all research in their field. But the scientists we met briefly above were not endeavoring to make dramatic changes or asking their colleagues to forget everything they ever learned. Their stories are stories of what I call “gratuitous resistance” — unnecessary impediments scientists face when trying to do their jobs.

False paradigms embraced and gratuitous resistance emplaced are part of a process I call “paradigm drift.” Whole fields may come to regard a guess, fashion, preference, or tradition as a paradigm — anything that lots of people like gets the paradigm treatment. Scientists and scholars who work with minimal preconceptions and who don’t respond to fashion find themselves trying to teach their peers the difference between paradigms and Pop-Tarts.

Imagine you have a friend who loves frosted Pop-Tarts and calls people who eat the unfrosted variety “junk eaters.” He respects only “frosted people.” One day, he announces a “paradigm shift” — he ate and enjoyed (!) an unfrosted Pop-Tart. Restraint is your superpower, so you do not giggle.

The obvious question to ask at this point is, “Is it really that bad?” I think Jane Goodall and the others would say, “Yes, it can really be that bad.” Paradigm drift can lead experts to claim that a guess “must be true.” I call this phenomenon “scientific delusion.”

Why would experts cling to theories based on minimal evidence and subject dissenting colleagues to blockades and bullying? This “why question” is a can of worms, worms writhing in human frailty, worms feasting on ego, power, and status. We will endeavor not to open it.

Instead, we seek a “structure of scientific delusion” that will enable us to identify false paradigms in situ as they are embraced by professionals without reference to any expert’s personal qualities or assumed motivations. An ideal “structure” would focus only on the general features of the discussion taking place between a possibly deluded majority and their rebellious colleagues: it would make paradigm drift as unmistakeable as a black dot on a white background.

First, we need a case study that will serve as a “touchstone of irrationality.” This would be a real or imagined case in which the progression from rational thought to delusion plays out in crisp detail as in a laboratory experiment. Our “structure” begins as a list of tactics commonly used to support false paradigms — a “textbook” example will endow our putative structure with depth and nuance.

Usually, the “perfect textbook case” has to be made up. But this time, there does exist a case, a tragedy, in which experts atop a hierarchy rationalized a delusion while effectively ignoring their horrified colleagues. An investigation produced a minutely detailed account of irrational certainty that began with hubris and ended with death.

In January of 1986, a small group of engineers cancelled the launch of the Challenger space shuttle. It was not safe to attempt a launch in cold weather. They suspected that the O-rings on the solid rocket booster would not seal properly at freezing temperatures. It was an easy decision because they knew rubber loses its resiliency in the cold. They sent a fax to NASA stating that the launch would have to wait for warmer weather.

The engineers then spent two hours explaining why it was not safe to launch. People with the power to make the final decision, experts themselves, over-ruled the engineers for no reason. Investigators expressed bewilderment during the hearings that followed the disaster. Aviation engineer Robert Rummel captured the general feeling:

I have great difficulty with this. In the usual practice, when there is any real doubt about flight safety, you simply don’t, and it seems to me this is the reverse, and I just have great difficulty understanding your answer. I just haven’t heard it as to why, if there was any doubt in your mind, why you went ahead, why you changed your mind. I just don’t understand it . . .

Rummel’s “why question” had no clear answer, but investigators did discover how a delusion can masquerade as a certainty: debating. In hours of sworn testimony before slack-jawed investigators, engineers and NASA officials recounted the process by which evidence-based reasoning was set aside in favor of a debate. “Cancel the launch” became “launch anyway.” It was the “structure of scientific delusion” come home to roost.

In Chapter 1, we will examine the transcripts from the hearings conducted by the Presidential Commission investigating the loss of the Challenger space shuttle. In Chapter 2, we will contrast what I call the “glorious side of the scientific coin” famously elucidated in Kuhn’s classic work with the grittier experiences of Goodall, de Waal, Clauser, Magueijo, Watson, Marshall, and Cheng. In Chapter 3, we will use the knowledge gleaned from the previous two chapters to create our “structure of scientific delusion.” In Chapters 4-7, we will use our “structure” to examine four ongoing cases of scientific delusion that may or may not be resolved in the lifetime of the reader.

Scientific delusion is unlikely to go away. So one might wonder what is the point of writing a book like this. Consider poverty. In Poverty, By America, Princeton Professor Matthew Desmond argues that the United States has the means to end all poverty within its borders with easily implemented policy changes. By raising awareness of what he regards as a moral failing, Desmond hopes to bring a rational approach to poverty closer to reality.

Similarly, irrational certainty need not blockade scholars. Journal editors can be impartial referees. Multiple viewpoints on many issues, including questions in which a large majority favors one answer, can be entertained without sacrificing scholarly standards. Nothing at all forces journals to be bastions of exclusivity: journal editors don’t have “rabid fan of the most popular viewpoint” in their job descriptions. Just the opposite should be true.

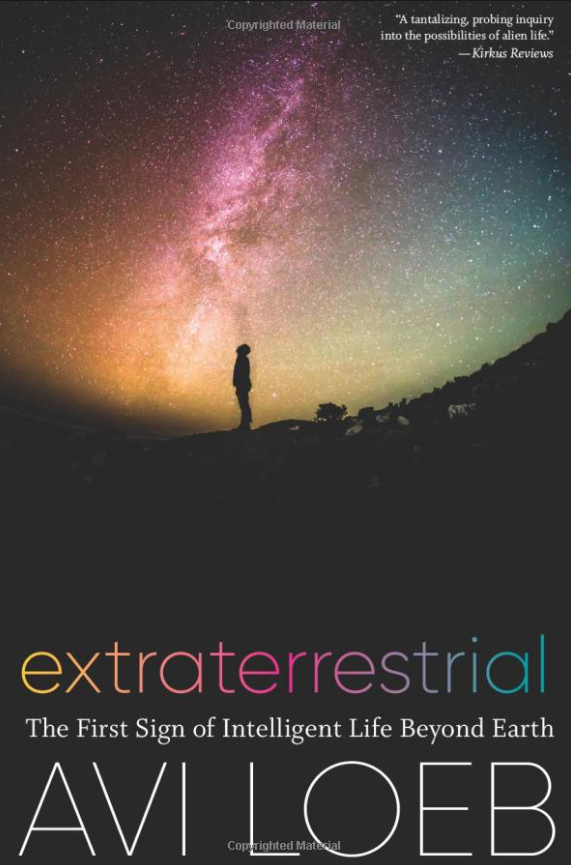

Consider the widely held theory (or guess, depending on who you ask) that the universe started fourteen billion years ago with a singularity and an explosive expansion of space often called the Big Bang. It’s a good theory and may well be correct, but a minority of credentialed experts question it. Even its strongest adherents admit the theory is far from perfect. Journals could regularly publish critiques written by credentialed experts, but they don’t. Already, this looks like a huge mistake: the new space telescope has produced embarrassing images of ancient galaxies that shouldn’t exist.

We won’t dig into the Big Bang question here mostly because things are changing so fast almost anything I think to type will be obsolete before it leaves my fingers. We will only say that the Big Bang is one origin theory within an astrophysical paradigm that says the universe is a complex system evolving according to the laws of physics. A full description of universal evolution is far beyond our abilities. Thus, a cosmology journal that doesn’t publish occasional critiques of the most popular guess is, effectively, lying.

A good theory is strengthened by criticism. And yet, credentialed experts with valid critiques of any given popular theory frequently find themselves censored by peers whose confidence would be a lot more convincing if they weren’t bragging in print about “walls” they’ve built to keep rebellious colleagues at bay. Real confidence is not so insecure. I think Eugenia Cheng is right about cultural norms: our culture would benefit from a shift away from groupthink and toward acceptance of uncertainty. And our scholars could lead us. My vision is optimistic, but, like Matthew Desmond’s vision, far from impossible.

Chapter 1: The Touchstone of Irrationality

On January 28, 1986, the Challenger space shuttle carrying the first “teacher in space,” Christa McAuliffe, and six professional astronauts, launched in historic Florida cold. Engineers who worked daily with the shuttle’s many components watched with sweaty palms. They knew the launch should not be taking place. A minute into the launch, one of the engineers breathed a sigh of relief because the most dangerous part had passed.

Thirteen seconds later, the shuttle exploded. The Presidential Commission convened after the disaster interviewed everyone involved. The Challenger case is so extreme, it is hard to believe and yet it is meticulously documented; as a touchstone of irrationality, it offers us rare, perhaps unique, clarity.

On the evening of January 27, 1986, a small group of engineers met to decide whether or not it would be safe to launch the shuttle in some of the coldest weather ever seen in Florida. These engineers worked for the Utah contractor (Thiokol) that built the solid rocket boosters (SRBs) that powered the shuttle’s takeoff. They made the “launch-or-don’t-launch” decision quite quickly (don’t launch) and then spent some time gathering data accumulated over dozens of shuttle flights.

The engineers suspected pairs of O-rings in six places on the SRBs might not work at low temperatures. When tons of a gooey hydrocarbon paste ignite, the O-rings must seal perfectly; otherwise, hot propellant gases will leak out the sides catastrophically. There is always fine line between a rocket and a bomb: the O-rings in six joints on the SRBs were that fine line.

The engineers knew that at some low temperature, the O-rings would become too “brick-like” to effectively seal the crucial joints. They let their bosses know the launch would have to be rescheduled. The bosses, experts themselves who had every reason to trust their colleagues, immediately sent a fax to NASA informing them that the launch could not take place in the cold. The fax arrived at 9:15 pm on January 27th.

Technically, the fax sent to NASA was a “recommendation,” but since NASA’s policy was to launch only with contractor approval, the fax, practically speaking, grounded the shuttle until the weather warmed up. Weather delays were routine. NASA’s response was unexpected.

Trouble began with the word “appalled.” A NASA official told the engineers and their bosses in Utah via a conference call that he was “appalled” by the postponement. Another NASA official added, “My God! When do you want me to launch, next April?” A two-hour debate followed.

NASA’s seemingly inflammatory, not-evidence-based-reasoning comments were repeated rather often in the media at the time. Cartoonists had a field day. NASA administrators told the Commission that their statements had been repeated without sufficient context. The chair of the Commission, William Rogers, was willing to accept the “context” explanation. The two-hour debate itself was of greater concern. Why was there any debate at all?

COMMISSION CHAIR WILLIAM ROGERS: . . . Do you remember any other occasion when the contractor recommended against launch and that you persuaded them that they were wrong and had them change their mind?

NASA OFFICIAL LARRY MULLOY: No, sir.

As testimony went on, a pattern began to emerge: a few poorly chosen words from the mouths of NASA officials were early warnings: the real problem was, as Rogers suggested, the lengthy debate itself in which evidence-based reasoning fell victim to a preconceived notion.

The engineers were worried about two temperature boundaries. After a flight at temperature X, engineers recovered the SRBs. They got a nasty surprise when they inspected the O-rings: thick black soot on the wrong side of a crucial O-ring dirtied the hands of unhappy engineers; disaster had come knocking. That’s why the fax sent to NASA set temperature X as a hard limit.

The other temperature, call it Y, was the lowest temperature any of the rocket components had been tested at. This temperature was lower than X. During the debate, the engineers pointed out that breaching the boundary set by temperature Y was a problem. Even if it could be argued that one could ignore the O-ring issue, why even consider launching below temperature Y?

Temperature X was 53 degrees; temperature Y was 40 degrees; temperatures in Florida were going to be in the teens overnight and not much better by morning. Engineers were sure of one thing: sixty degrees in a few days was safer than thirty degrees today. The Commission wanted to know why NASA officials disagreed.

MULLOY: I didn’t find that argument to be very logical at all . . .

ROGERS: Why is that not logical if he said why don’t you at least require a 40 degree temperature? You say you didn’t think it was logical. It seems very logical to me.

MULLOY: Not on an engineering basis, sir. If one was concerned about data that said 53 degrees is unsafe, there is certainly no logic for launching at 40 degrees.

Rogers had a hard time with Mulloy’s “logic” as evidenced by language, tone of voice, facial expression, and the exchange which followed.

ROGERS: What is troubling, very seriously troubling, is why this is such a convincing matter to you, you are certain of these things, you are sure it’s okay. How come then in a matter of such major importance, involving the lives of seven astronauts, you apparently were not able to convince any of the engineers . . . that you were right.

MULLOY: I was not aware they were not convinced.

This last statement opened up a new line of inquiry. All NASA officials interviewed said they didn’t know the engineers were not convinced. These officials, including Mr. Mulloy, said they would not have launched had they known that the engineers had been over-ruled by their bosses.

Phone lines were indeed muted for half an hour after the debate, so it is indeed the case that NASA officials did not hear the conversation in Utah that followed the debate.

During that half hour, three of four managers made it clear they wanted to launch. The engineers repeated what they had been saying for the past two hours: it’s too cold. One of the managers, Bob Lund, didn’t want to over-rule the engineers, but Lund’s boss, Jerry Mason, said, “It’s time for you, Bob, to take off your engineering hat and put on your management hat.”

Bob Lund did as suggested and the four managers unanimously over-ruled the engineers in favor of what NASA had spent two hours pushing for. They got back on the phone with NASA. The launch was now approved. NASA got a new fax signed by Thiokol executive Joe Kilminster. The new fax said that the secondary O-ring should hold even if the primary O-ring fails.

Commission members found the decision process almost incomprehensible: conclusive data to determine the minimum safe O-ring temperature did not exist; a two-hour debate focused on the unquantifiable nature of the data but produced no other insights; a half-hour discussion led to a second fax approving the launch; the secondary O-ring holding was nothing more than wishful thinking.

COMMISSION MEMBER ASTRONAUT SALLY RIDE: The engineers’ main problem was that they felt their temperature data was inconclusive and they were worried about it, but they didn’t have the data to quantify what problems the temperature could cause. And that was [the basis for] their recommendation not launch in the first place . . . Did you think you had proof? Did you think you had the data to show it was safe?

COMMISSION MEMBER GENERAL DONALD KUTYNA: If this were an airplane and I just had a two-hour argument with Boeing on whether the wing was going to fall off or not, I think I would tell the pilot, at least mention it . . .

NASA officials responded to Ride and Kutyna and other Commission members who pushed them on these points by repeatedly — more than ten times — noting that the final decision was the contractor’s to make.

MULLOY: I rely on Mr. Kilminster to sort all of that out and make a flight readiness recommendation, and he has been doing that for some twenty-four flights now.

NASA OFFICIAL GEORGE HARDY: I clearly know in my mind . . . and again reiterate the fact that I would not recommend launch over the contractor’s objection . . .

Did you think you had proof? Dr. Ride’s question was, ultimately, the bottom line. The idea that the launch could take place because the engineers couldn’t prove an explosion was guaranteed was bewildering to Commission members. Bob Lund’s testimony offered the Commission, finally, a view of a descent by decent people into irrationality.

ROGERS: How do you explain the fact that you seemed to change your mind when you changed your hat?

THIOKOL EXECUTIVE BOB LUND: I guess we have to go back a little further . . . I had never had those kinds of things come from the people at NASA . . . And so we got ourselves into the thought process that we were trying to find some way to prove to them it wouldn’t work and we were unable to do that. We couldn’t prove absolutely that [the SRB] wouldn’t work.

ROGERS: In other words, you honestly believed that you had a duty to prove that it would not work?

LUND: Well, that is kind of the mode we got ourselves into that evening. It seems like we had always been in the opposite mode. I should have detected that, but I did not . . . The roles kind of switched . . .

COMMISSION MEMBER JOSEPH SUTTER: Why didn’t you just tell them it’s our decision, and this is it, and not respond to the pressure?

LUND: As a quarterback on Monday morning, that is probably what I should have done, but you know you work with people and you develop some confidence and I have great confidence in the people at NASA . . .

COMMISSION MEMBER ARTHUR WALKER: But when it was predicted the temperature at launch was going to be twenty-nine degrees, the O-ring was outside of qualification.

LUND: That is correct.

WALKER: Then how could you make the recommendation to launch if you were more than ten degrees outside of your lowest temperature qualification?

LUND: Our original recommendation, of course, was not to launch.

ROGERS: But something caused you to change your mind. What was it?

LUND: I guess one of the big things was that we really didn’t know whether temperature was the driver or not . . . The data was inconclusive . . .

COMMISSION MEMBER RICHARD FEYNMAN: But logically, from the point of view of the engineers, they were explaining why the temperature would have an effect, and when you don’t have any [conclusive] data, you have to use reason, and they were giving reasons.

LUND: That’s right and that is why we included in the fax the fact that temperature could have an effect on the O-rings.

COMMISSION MEMBER ROBERT RUMMEL: I have great difficulty with this. In the usual practice, when there is any real doubt about flight safety, you simply don’t, and it seems to me this is the reverse, and I just have great difficulty understanding your answer. I just haven’t heard it as to why, if there was any doubt in your mind, why you went ahead, why you changed your mind. I just don’t understand it . . .

Jerry Mason, the man who had asked Bob Lund to put on his “management hat,” further clarified the burden-of-proof reversal as a key step in a series of steps that led to disaster.

THIOKOL EXECUTIVE JERRY MASON: . . . So every flight which the program has had has had to break some frontiers.

RIDE: The time you go through frontiers is during testing, not during the flight. That’s the way it’s supposed to work . . .

. . .

WALKER: Twenty-five degrees outside of your experience base is a large extrapolation.

MASON: That is the certainly the reason we had the extensive debate . . . we listened to all the arguments and we found ourselves in a position of some uncertainty that we were not able to quantify . . .

. . .

COMMISSION MEMBER DAVID ACHESON: . . . it comes down to a point of view that says the burden of proof is on the people who want to launch . . . and another point of view that says the burden of proof is on the people who want to stop the launch . . .

. . .

MASON: Since the incident, we have been searching our minds and our souls on the question of did we address it properly. You know, everyone has said if I could have stopped it, I wish I had. But here we are, trying to present the thought process that we went through that day rather than what we could do over.

When Challenger exploded, data suddenly existed to produce a rough probabilistic model for shuttle launches at freezing temperatures. One SRB joint leaked; five held. Here’s the model: roll six dice simultaneously; if you roll any ones, everyone dies. A coin toss would be safer.

The engineers suspected the launch was a coin toss at best, but they couldn’t prove it. They cancelled the launch but had the decision taken out of their hands. The second phone call was a formality undisrupted by engineers who had tried their best to prevent the launch.

One of the engineers, the one on-site in Florida, said this to NASA officials: “If anything happens to this launch, I wouldn’t want to be the person that has to stand in front of a Board of Inquiry.” He received for his trouble a rhetorical pat on the head: “It’s not your concern.”

In Utah, after Bob Lund put on his “management hat,” two engineers got out of their chairs. They placed photographs on the table. Black soot on the wrong side of damaged O-rings told, for them, a clear story.

“Look carefully at these photographs,” one engineer said to four managers. The other engineer repeated the gist of the arguments and reiterated the conclusion: don’t launch. All they got were cold stares.

Engineer Bob Ebeling watched his colleagues getting stared down. He didn’t think the launch was even as safe as a coin toss. Ebeling left the office, went home, and boiled it down for his wife, Darlene: “It’s going to blow up.”

Ebeling died in 2016 at the age of 89. Before he died, he told the world via an NPR interview that he had never forgiven himself for not doing more to stop the launch. He didn’t say what precisely, he wished he had done. He just said this: “He shouldn’t have picked me for the job.” Ebeling, a religious man, was talking about God. “He picked a loser.”

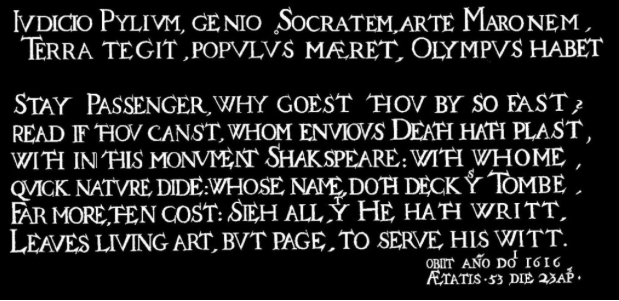

Nobel laureate Richard Feynman, one of the physicists on the Commission, believed the problems at NASA ran deep. He didn’t mince words when he concluded his appendix to the Commission’s report as follows: “Reality must take precedence over public relations, for Nature cannot be fooled.”

Indeed, the space shuttle in orbit at the moment the President of the United States gives the State of the Union address would have been a public relations boost for NASA. Unfortunately, NASA officials were good at fooling themselves, frequently engaging, according to Feynman, in “fantasy” when discussing the shuttle’s safety. NASA officials ignored reality.

You don’t need a Nobel Prize to recognize three signs of irrational certainty: tough language offered as the answer to evidence-based reasoning; twisted logic and wordplay used as weapons; demands for proof on the one hand and hopeful scenarios presented as fact on the other hand. The great tragedy of the Challenger disaster is this: anyone, even a child, listening to the engineers and to the NASA officials, would have said, “Don’t launch.”

A fax that says, “Don’t launch below fifty-three degrees” is not ambiguous or complicated. The world is a complex place, but it is also a simple place. This is not a paradox: a central claim of this work is that a rational assessment of the rough level of certainty — a coin toss versus absolute certainty — about even the most complex question is within the capability of non-experts. Complexity is not a cloak of darkness.

*********************************

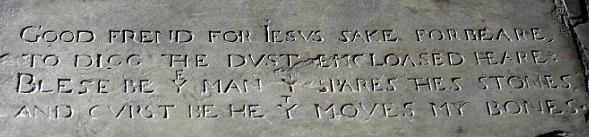

An elegantly dressed woman, upon learning of evolution is said to have fainted. Upon waking, she is said to have said, “I hope it is not true, but if it is true, I hope it does not become generally known.” The shock experienced by our apocryphal woman and other, real people, was the harbinger of what Thomas Kuhn called a “paradigm shift.”

The original paradigm, the idea that species don’t change, was rational, logical, and useful, but was also (as always) an imperfect version of reality. When Darwin and Wallace took the long view, the natural world transformed before scientists’ eyes: species do change. It was a classic Kuhnian paradigm shift: a deeper, clearer view of the world remade a scientific field. It was a revolution. It was glorious until scientists started to embarrass themselves.

First, the glory.

Evolution still has the capacity to surprise us even long after its introduction. Consider the appearance of single-celled life: every day it seems, the oldest cell gets pushed further back, closer and closer to the formation of the earth itself. It’s almost as if life was meant to be. But then billions of years passed as single-celled life gradually altered itself.

Finally, after three billion long years, multi-celled life appeared. Fish, amphibians, reptiles, and land mammals grew more and more complex in “mere” millions of years. It’s almost as if they were tired of waiting to exist.

Fifty million years ago, the dinosaurs were gone, land mammals thrived. Then the evolution paradigm showed off a bit as some of these mammals evolved back to the sea and into its depths. Ten million years was enough to turn four-footed, furry land mammals into hippos, sea lions, and whales. Ten million years is enough time to have a good chance of flipping forty-six heads in a row and long enough to turn a meat-eating zebra into a whale. So says the fossil record. But that’s nothing.

The elephant’s ancestor was one of the mammals that began to exploit the tropical coastline. Modern elephants retain much of their coastal heritage: they are impressive multi-mile swimmers; one theory even says the trunk first evolved as a snorkel! Some the elephant’s ancestors followed a different path — one that did not return to the land. The fully aquatic manatee is, in an elephant’s eye, a real-life mermaid.

Have you fainted yet? It isn’t at all irrational for scientists (and shocked personages) to regard a new paradigm with a certain amount of suspicion. We’re used to it now, but can we blame 19th century scientists for thinking evolution was just absolutely bonkers? Kuhn pointed out that if scientists weren’t a bit clingy when it came to the basic assumptions of their field — paradigms — they wouldn’t get much done. If they didn’t resist paradigm shifts, Kuhn says they would be “distracted too easily.” So a bit of resistance he regarded as a good thing.

However — and this is a big however — not every popular idea is a paradigm. Even if a theory becomes conventional wisdom, that does not make it a basic assumption underlying the whole field. And no matter how smart you are, your guesses are still just that, guesses.

Every now and then (more often than we would like) scientists, scholars, and experts of all kinds wake up and find that they have fallen into a banal trap — they have fooled themselves. They thought they had a paradigm on their hands, but actually all they had was overconfidence.

Eventually, hubris bows to reality. Naked emperors wrap their shiny butts in handy blankets. It’s not a revolution. It’s not a paradigm shift. It isn’t shocking. There’s no glory. If it isn’t tragic, it’s embarrassing.

In Bones of Contention, Roger Lewin suggests those scientists who study human evolution are especially vulnerable to the blandishments of the weavers of fine cloth — Lewin does not exclude himself. For a big chunk of the twentieth century, Lewin and most of his colleagues were absolutely sure about oh-so-many things about our earliest ancestors. They pronounced and propounded, but the evidence didn’t cooperate. The paradigm (evolution) survived just fine, but guesses claimed as certainties and pushed like paradigms were all embarrassingly wrong.

“I will never again cling so firmly to one particular evolutionary scheme,” said David Pilbeam after the dust had settled. The Harvard professor’s warning is, as we will see, apt for the ears of many an expert attracted by the siren song of excessive certainty. But the warning hasn’t made much headway even among Pilbeam’s blushing colleagues who do seem unduly attracted to what I call “false paradigms.”

This is the other, darker, side of the scientific coin. Between glorious Kuhnian revolutions we get to experience a fair quantity of not-so-glorious posturing, often by people not wearing so much as a fig leaf. Lewin, Pilbeam, and the present author know all about it and we three are not, as we will see, the only scientists to make note of it. Almost any scientist you can find — from James Watson to Jane Goodall — knows about this other side of the coin and complains about it, sometimes bitterly and sometimes laughing it off, but one never gets the impression that posturing is not a too-large part of the scientific process.

Complaints are understandable, but what is needed is a systematic study. Let us start with a famous debacle in the study of human evolution, a debacle whose embarrassing story continues to unfold even now.

How did it come to pass that our ancestors left the trees? Spoiler: no one knows. With minimal fossils and no time machine, scientists guessed. It was, at first, a tentative guess and as such an invaluable first step toward understanding.

Daniel Willingham’s Outsmart Your Brain explains the importance of guessing in learning. A guess puts everything in context. When we learn something that impacts the correctness of our guess, that which we learned has a place to go in the landscape the guess created in our brains. So, Willingham, says, go ahead and guess. Then congratulate yourself or modify your guess slightly or modify your guess significantly or toss your guess out entirely — it’s okay to be wrong.

So scientists guessed that since modern humans can hunt rather successfully with fairly simple tools, perhaps a group of tree-dwelling human ancestors with small brains gradually developed into bipedal hunters. With their hands free to carry and use tools, these “bipedal apes” would have a big advantage over the other apes. “Man the Hunter” was born.

Some scientists noted that the tool-wielding ape was maybe a bit of stretch even if the creatures were walking on two legs as the fossil record showed. The problem was the tools hadn’t been discovered. These scientists thought these bipedal apes might have lost their hair and gained a fat layer during the same evolutionary period that had them standing up. Maybe they looked more like us than we usually imagine. Maybe they were exploiting a new habitat with tools no more sophisticated than rocks and sticks.

Both guesses fit the prevailing paradigm. Both were based on evolution. Both emphasized challenges, pressures, inherited advantages, access to food, reproductive success, and so on. But Man the Hunter was more popular. It became the “leading theory.” The other theory didn’t even have a name. The trap is set.

A lot of scientists favored the leading theory and scientists are smart so we might as well consider the leading theory to be correct until proven otherwise. Confidence, after all, is a virtue. We don’t have any alternative theories that have been proven beyond doubt. Let us therefore confidently squash dissent. The trap is sprung.

This is “paradigm drift.” For many years in the middle of the twentieth century, Man the Hunter was regarded not just as one possibility or even as a possibility embraced by most scientists but rather as foundational for the whole field of human evolution — a sine qua non for anyone who hoped to join the club of professionals. But without which nothing is a dangerous phrase to apply to a guess, even one that has been developed into a tentative theory by many smart scientists.

Man the Hunter was a classic “false paradigm” — popular but without sufficient evidence behind it to make it any more certain than a coin toss. Man the Hunter was not the kind of idea that can serve as the foundation of an entire field. It was an idea that, if wrong, could easily be abandoned in favor of any number of alternatives.

Scientists had alternative ideas. One rebellious expert developed his own theory (which was also in the mind of at least one other expert who came to the same conclusion independently) for how upright human ancestors with smooth skin on top of a fat layer might have survived. His friends, fearing for his career, advised him to remain silent; he heeded their warnings.

Thirty years later, after a successful career in which he didn’t challenge popular guesses, after having been knighted, this scientist finally outlined his theory of upright human ancestors with small brains surviving with minimal tools. Derision, vitriol, and bullying followed. He was treated as if he was claiming aliens had landed in his backyard.

But the mass of scientists up on their high horses did not ride off into the sunset: they were headed for a cliff. Tools capable of supporting even a simple hunting lifestyle did not exist until our ancestors had been walking upright for millions of years. As a theory explaining the origins of the human line, Man the Hunter was a failure.

Whatever these bipedal apes were doing, they weren’t carrying tools in their free hands. Circa 1970, Man the Hunter was dropped like a hot rock by embarrassed scientists. It wasn’t a scientific revolution. It was a disaster. The best that can be said for it is that no one died.

Today, Man the Hunter lives on in the consciousness of many non-professionals, but no scientist today subscribes to it and no theory has replaced it. The only thing scientists are absolutely certain about is that the theory put forward in 1960 by Sir Alister Hardy must never be accepted. Hardy died in 1985 after having received zero mea culpas from his colleagues.

The famous biped called Lucy strolled along the shore of an African Lake walking every bit as well as we do with no spear and no stone knife but perhaps with smooth skin and a curvy body just as Hardy imagined her. No one knows how she lived (except that it wasn’t what Hardy said) and journals are wide open to (non-Hardy) speculations about Lucy’s way of living: she stood up carry food, to threaten, to pick berries, to keep cool, to walk long distances, to cement the pair bond, to see over the tall grass. Anything goes — almost.

One wonders what is so terrible about Hardy’s theory. He asked his colleagues to consider other mammalian orders in which a species exploited a new habitat and evolved changes to posture, fur, and fat. Where, he asked, would a group of modern humans wish to go to survive for a few years naked with no tools? Is the problem with Hardy’s theory that it’s too obvious?

Daniel Dennett knows all about the “anti-Hardyism” practiced by the establishment. Dennett is a philosophy of science professor at Tufts University and an expert on evolution. He is the author of a dense and beautiful treatise called Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. Dennett regards evolution as a sort of “meta-paradigm” — an idea so powerful it has changed the way we think about pretty much everything. Most of his book was devoted to his major points, but, as an aside, he noted the odd disconnect between the straightforward nature of Hardy’s theory and its negative reputation among most professionals.

The reader will perhaps not be surprised that Hardy believed our early ancestors may have exploited a tropical coastline. Hardy did not imagine our ancestors living in the water or swimming and diving any more effectively than we do today. The “aquatic theory,” as it is sometimes called, just says the two swimming primate species — proboscis monkeys and homo sapiens — developed their swimming ability due to the usual evolutionary pressures.

Proboscis monkeys, living in the swamps of Borneo, swim, sometimes underwater, to move from place to place in their habitat. Changes to their physiology vis a vis other primates are evident and clearly result from their watery lifestyle. Proboscis swimming is not impressive by human standards, but they are the top swimmers among non-human primates.

As primate swimmers, Hardy pointed out, humans are in a class by themselves. Some humans swim the English Channel or dive a hundred feet without benefit of high-tech gear. Extreme distance swimming and hundred-foot “free dives” come only with extensive training, but a human baby, with ordinary parental supervision and plenty of pool time will walk, talk, swim, and dive by age two often swimming first and walking second.

There is of course no mystery to our swimming ability at least in terms of its physiological origins: our posture is streamlined; we have an insulating, buoyant fat layer unique among primates; we are famously the “naked ape.” Thirty feet of water, deadly to a gorilla, is a comfortable hunting ground for humans like Shimoko Matsumoto whose ancestors have been diving for edible bounty (for pearls only recently) for centuries at least and probably for millennia.

A handful of professionals openly say they find Hardy’s focus on physiology and modern human behavior compelling (Dennett reports many people who favor the idea only say so in private conversations). These brave professionals note that swimming mattered for our ancestors at least as far back as two million years ago when they were definitely eating catfish and they point out that many humans who are not hardcore athletes can do half-mile swims across Walden Pond. Physiology makes this possible: a troupe of hypothetical gorillas living near Walden Pond would be as likely to be seen swimming across it as flying over it.

Hardy, perhaps influenced by his marine biology background, saw human swimming as the single most striking result of physiological differences between humans and the other primates. He challenged his fellow scientists to come up with an equally simple theory that explains the differences and that has precedent in other mammalian orders.

Most modern scientists, however, believe human swimming is merely fortuitous, like chess-playing and they might be right. Analytical ability allowed Judit Polgar to play the king’s gambit in 2010 and a grandmaster went down in defeat, but the king’s gambit had no survival value for Judit’s ancestors. Polgar’s prodigious analytical ability evolved — almost everything we do has some kind of evolutionary root — but it had nothing to do with chess. Chess-playing is a happy accident for those of us who enjoy using our enhanced cerebral cortex to manipulate knights and bishops.

In theory, the streamlined, fat-covered naked ape diving for oysters in Japan or swimming in Walden Pond in Massachusetts might be capable of doing so due to a “happy accident” of evolution. Any particular capability displayed by modern humans may or may not have, itself, driven the evolution of our ancestors.

What I call the “happy accident theory” (HAT) of human evolution says the same physiological changes that evolved in other mammals as a result of their exploitation of a coastal habitat evolved in humans for reasons unrelated to coastal living. The HAT might be true: it is possible that our ancestors’ exploitation of coastal resources was occasional and opportunistic and not, as Hardy suggested, the key change that created humanity.

Possible and certain are not synonyms, however. And there’s the rub. Lucy either was an upright, smooth-skinned, curvy swimmer or not. No one knows. Hair and fat don’t fossilize. Hardy vs HAT is a coin toss, but the coastal theory is kept out of the journals and not mentioned in textbooks.

For the purposes of this discussion, it would be better if Hardy turns out to be right. Otherwise, the majority of scientists will be able to claim that they were looking at the issue rationally. But unless one has magic powers and can predict the future, a coin toss is still a coin toss.

Geneticists will eventually isolate the genes responsible for our ability to swim and genetic changes can be dated by looking at mutation rates, so we’ll know one way or another eventually. If the geneticists determine that the crucial changes date to the same period, if Lucy was Lucy Ledecky, scientists claiming absolute certainty about the HAT will have to put on a dunce cap, sit in the corner, and write “I will respect my professional colleagues” a thousand times.

The whole anti-Hardy spectacle strains credulity. Can professional scientists, trained experts, really look squarely at a coin toss and see certainty? Is this level of irrationality, a level that can only be called delusional, really afflicting virtually an entire field full of experts? It’s hard get one’s mind around this. Most of us prefer to trust our experts (I know I do). And really, what choice do we have? But what if our experts seem to have lost touch with reality? What then? Professor Dennett, our resident expert on evolution, wondered about this phenomenon as well.

At conferences, it was often the case that Dennett couldn’t walk two steps without bumping into a fellow expert on evolution. He had many opportunities to satisfy his curiosity and he made the most of them. He asked about Hardy and then asked again. Why untouchable? What is so wrong with it that it is “pseudoscience” and “crackpot” nonsense comparable to “creationism” and therefore unworthy of discussion? Whence come these insults?

Professor Dennett has degrees from Harvard and Oxford. It’s hard to imagine anyone more in the mainstream of scientific thought or anyone more knowledgeable about the practice of science in general and about evolution in particular. Dennett posed his questions (paraphrased above) to colleague after colleague. He spent years asking. In his book, Dennett gives only the number of responses he received that he regards as coherent — zero — and leaves it there.

Perhaps this book should be dedicated to Professor Dennett. After all, it’s hard to imagine a more concise and simultaneously powerful way to make note of the problem I wish to address here. Zero coherent responses. That’s a strong claim. As we will see, the published critiques of Hardy’s theory bear out Dennett’s claim. The critiques follow a recognizable pattern central to our discussion: evidence, logic, and reason are set aside in favor of a tactical approach designed to defend a preconceived notion at all costs. We will elucidate this pattern. But we have some work to do first.

Chapter 1: The Four Horsemen of the False Paradigm

THIS IS ALL INCOMPLETE FROM HERE SO I WOULDN’T BOTHER WITH IT. ONLY THE INTRO IS REALLY DONE.

The battle to block VSL followed the pattern we will see in the ten examples we will look at here (I guess VSL is our “zeroth” example). The first thing you have to do if you want to prevent all creativity, block all original thought, push hard the idea that “anything new is bad” (that’s from Joao’s book) is get away from evidence. The best way to get away from evidence is to start with insults like “very silly” and move on to nonsense. Joao describes some of his colleagues as behaving like “rabid dogs.”

Next those whose lifework is to defend tradition can move into the evidence-based part of the battle. The key is to reverse the burden of proof. In other words, the old theory is right as long as it is possible that it is right. You are the authority so possible is good enough. If you can create plausible scenario, even if you have to make it up, even if your scenario is unprecedented, intrinsically unlikely, and/or just plain idiotic, that doesn’t matter.

The old theory or the preconceived notion is automatically assumed to be true unless the challengers have absolute, 100%, perfect, untouchable, video-and-audio-and-fifty-eye-witness proof that their new theory is right, the old theory will continue to be the standard no matter how weak it is. Reversal of burden of proof happens all the time.

In science the burden of proof is not supposed to be placed on any particular scientist but often is. The claim is often made, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” where an “extraordinary claim” is any idea that isn’t the old idea. In Joao’s case, his claim that the speed of light might not be constant over astronomical timescales was treated as “extraordinary.” However, physicists have zero idea about this: there is nothing even slightly extraordinary about the claim. Either the speed of light evolved or it didn’t. We just don’t know.

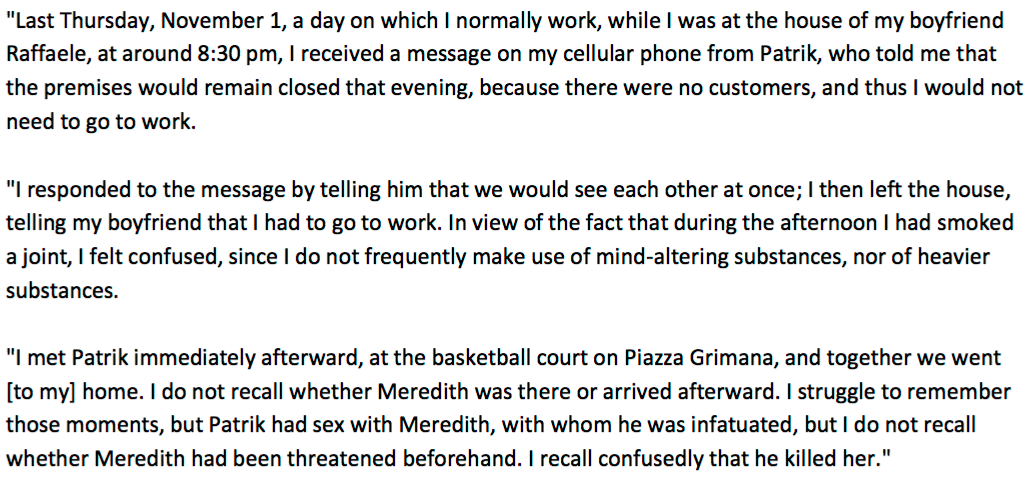

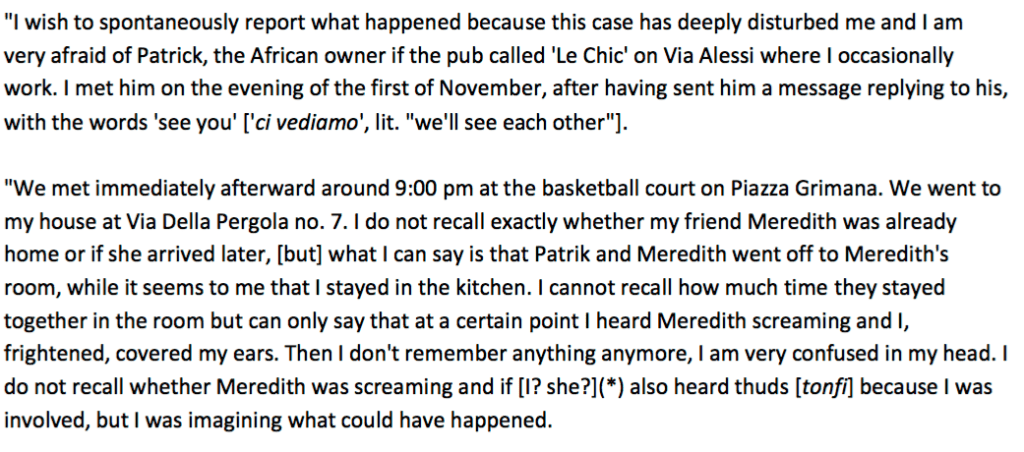

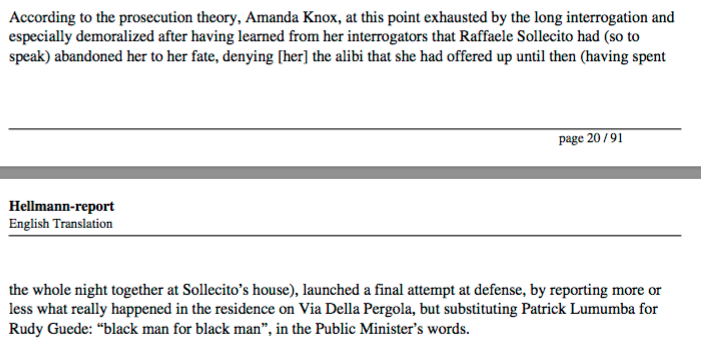

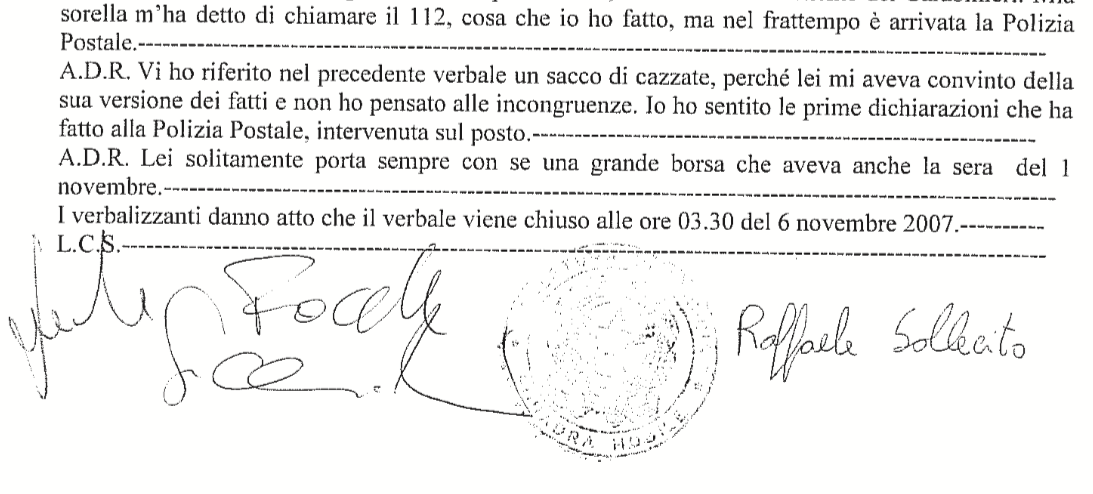

In a courtroom, the burden of proof is supposed to be placed on the prosecution. And yet legal scholars know well that juries can easily drop “innocent until proven guilty” and drift into “guilty unless proven innocent.” All it takes is a taste of a preconceived notion and suddenly a jury is perfectly willing to believe someone who has a provocative tattoo is guilty of murder even when there is no real evidence. People can die as a result.

This process in which evidence is first ignored via insults and nonsense and in which burden of proof is used as a weapon to elevate plausible scenarios for the mainstream and crush even very solid evidence presented by the mainstream’s rebellious colleague is something we will see again and again. I call insults, nonsense, plausible scenarios, and demands for perfection the “four horsemen of the false paradigm.”

A “false paradigm” might be a preconceived notion or an outdated theory or just a plain old mistake or even an unstated assumption that has been accepted by so many people for so long that it has become entrenched. It might come from a time before there was any real evidence either for or against it and it might have become entrenched just by happenstance. A mountain of new evidence might contradict it to the point where if it were proposed now, it would just be laughed it.

In Joao’s case, he ran into an unstated assumption that the speed of light has been constant from the beginning of the universe. It wasn’t even a theory, it was just what was in the back of physicists’ minds because the speed of light is called a physical constant and “constant” must mean constant forever. But of course it means no such thing. In the Challenger case, the false paradigm was a preconceived notion — the shuttle is safe unless I see it actually explode.

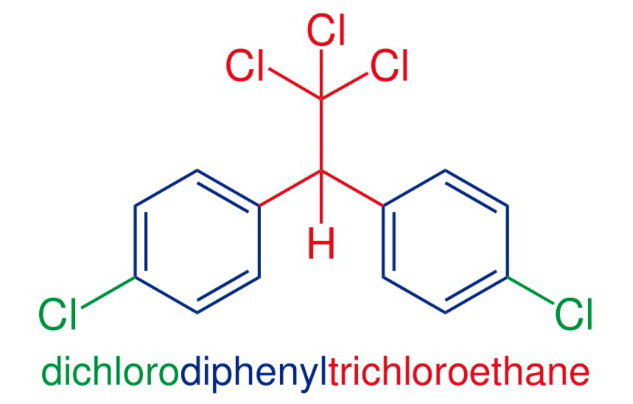

We will look at a false paradigm that resulted from a mistake made by a medical researcher that was accepted as fact and that persisted for forty years while people (including my great uncle) died from a curable illness. We will look at a false paradigm in chemistry that was a guess made before chemistry was even invented and that has persisted to the present day as common knowledge even though modern chemistry has pretty much proven the old guess to be a dead end useless theory that scientists regularly champion but never actually use. In this case, a number of credentialed experts have stated a simple and compelling alternative theory — I’ve spent years looking for any coherent refutation of this alternative idea and have found nothing but insults, nonsense, plausibility arguments, and demands for perfection.

False paradigms can be identified of course by mainstream “four horsemen” arguments. But false paradigms also have a two interesting precursor characteristics that can allow for a “quick and dirty” identification. The first question to ask is, “What happens if you reverse the hierarchy?” In the Challenger case disaster would have been averted by simply asking Christa McAuliffe (or one of her high school students) to weigh in. In Joao’s case, any student studying physics could be asked whether or not we should consider the possibility that physical constants can evolve and all would say “of course.” Only the arduous process of becoming a tenured professor would cause someone to worry that the idea is too “radical.”

The other trick aside from a hierarchy reversal (or just asking yourself what happens if we reverse the hierarchy) is to check to see if the theory you suspect is a false paradigm is actually ever used and if it is used, it is being used successfully. There are, after all, many useful paradigms in engineering, medicine, and science and they become deeply entrenched not simply because a lot of people accept them but because they are amazingly useful. These paradigms I call “Kuhnian paradigms” after the philosopher Thomas Kuhn who wrote The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Kuhn made a strong case that paradigms used by experts are good things even if they are a little rigid sometimes because they are so powerful that they allow experts to make progress that would be impossible if said experts were constantly questioning the paradigm. So Kuhn’s book might be said to be about the bright side of the paradigm coin.

False paradigms are the dark side. They are NOT useful or powerful. And their lack of value and power is often evident because a false paradigm might have never even been proposed before it was needed to block someone’s idea — it might have been made up just for the occasion. Or a false paradigm might have been accepted for a long time but effectively ignored by researchers who have to ignore it because if they didn’t, they would get stuck and never make any progress. Or a false paradigm might get used a lot with horrific results.

In the Challenger case the theory that “the space shuttle is safe” was brand new. The engineers who were used to the essentially the opposite assumption — space flight is dangerous — normally had to prove to skeptical people at NASA that this or that concern had been adequately addressed. They were blindsided by the sudden appearance of a new (false) paradigm, one that hadn’t existed before that day in 1986.

In Joao’s case too, the false paradigm he had to deal with — the speed of light is constant on astronomical timescales — might have been a tacit assumption in the backs of the minds of many physicists but was never a theory. Joao, like the space shuttle engineers, was fighting a ghost, a theory that came into existence just to stop him from publishing.

The medical case in which people died for forty years because of a mistake we will see came about because of a false paradigm that took hold but was largely useless: doctors used it to try to help people but usually failed. In the chemistry case, the false paradigm has simply been ignored: the theory is probably wrong but this fact has little practical impact because no one uses it to do anything which is a good reason to consider moving on (aka getting off the table and getting dressed). I doubt either of these theories could have convinced students if they, the students, were allowed to form any opinion they wanted to: again, sometimes only tenured professors are vulnerable to false paradigms.

So we’ve got our two precursors: a previously nonexistent or useless theory might be a false paradigm; a theory that would instantly crumble with a reversed hierarchy might be a false paradigm. And we’ve got our four horsemen. If the mainstream is challenged by their own colleagues and they respond with insults backed up by nonsense, gibberish, foaming mouths, circular reasoning, and wild illogic we can then expect two more horsemen to come forth and mindlessly defend the status quo with plausible scenarios presented as certainties and demands that all new idea be perfect and proven beyond doubt.

False paradigms are, this essay hopes to show, self refuting. As a result, this essay claims, they are not only easy to identify but this identification can be established by any thoughtful group of people via consensus: no clever debating is necessary. Members of this hypothetical “thoughtful group of people” might disagree about the probability of the mainstream’s false paradigm someday being proven correct after all (50%, 10%, 1% or 0%) but, I claim, can agree on the status of the paradigm as false — as an idea claimed by experts to be virtually certain that is in fact very much up in the air and that is disputed by a minority of experts.

Of course, there may be false paradigms that are accepted by all experts but those are, as the saying goes, “beyond the scope of this work.” It’s hard enough dealing with the false paradigms for which there is extensive minority expert commentary explaining why the mainstream has mired itself in cement. Trying to marshal one’s facts in the case of a suspected false paradigm and making the crucial first step of determining what common ground exists for all observers is just too hard without credentialed experts who have weighed in. “Too hard” doesn’t mean “impossible” of course but we’re not going to attempt it here: all four of the modern false paradigms we discuss have extensive expert analysis and a clear common set of facts for us to work with.

Before we see how the four horsemen killed seven people aboard the Challenger and before we walk through the graveyard populated with the victims of five other false paradigms and before we look at how the lack of a culture of open discussion in our scholarly community has led to the adoption of at least four false paradigms by practically the whole world, it behooves us to have look at Kuhn’s work. After all, he coined the term paradigm shift and my use of the word “paradigm” was inspired by his work.

Kuhnian paradigms are as different from false paradigms as can be imagined: when a Kuhnian paradigm is overthrown, that’s a scientific breakthrough and everything changes, but when a false paradigm is finally cast off, progress continues as before but without the ball and chain of a dead end idea. But, as the reader has undoubtedly guess, there is an important connection between the two side of the paradigm coin.

Each of these cases will have its own “Monday morning quarterback” moment, the commentary from the mainstream that reveals why they are not susceptible to discussion, logic, evidence, or even reality itself. In the Challenger case, part of the tragedy is that the engineers — many of whom still feel guilty today because they weren’t able to get through to their colleagues — didn’t know what they were up against.

Part of the motivation of this essay is to provide us with some understanding of just how bad bad can get when a preconceived notion gets its jaws around our experts. With understanding may come strategies for reform and improvement to systems and for dealing with mindless resistance to reality when it does rear its head. We’ll discuss some of these strategies in the following chapter.

Insults, nonsense, perfection, plausibility. Get away from evidence. Reversal of burden of proof.

Reverse hierarchy, squash dissent, ignore own theory, adjust theory.

Rating system

To understand the ubiquity of folly we will look at six examples from the past in which intelligent, credentialed, upstanding, experienced, authoritative, good-looking, well-dressed, well-paid, well-spoken, professional, decorated, titled, highly respected, thoughtful, decent, caring, knowledgeable experts claimed absolute certainty. In these six cases, the fools weren’t so lucky. People died, in some cases a lot of people.

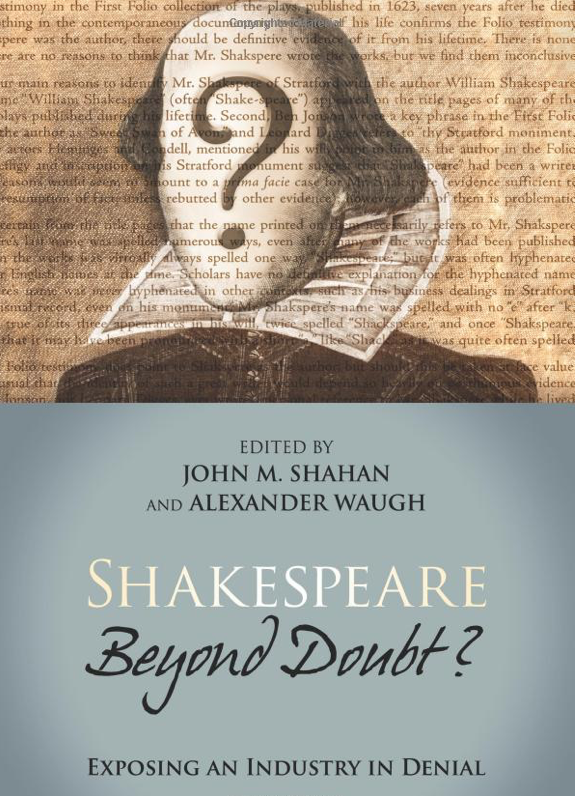

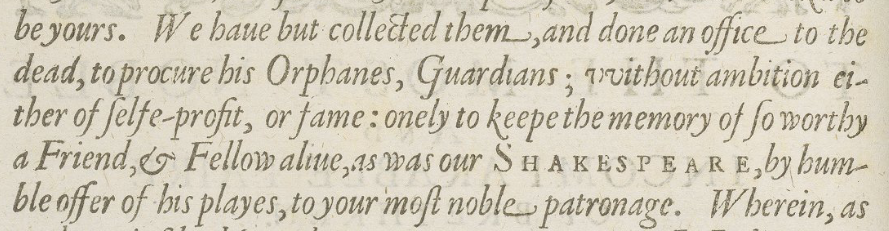

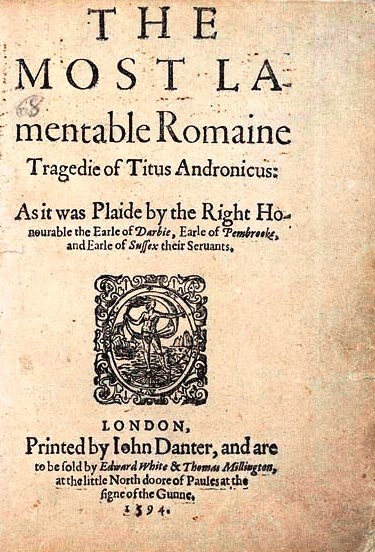

Armed with the six horrific lessons and having examined the commonalities that bind them together, we will next look at four non-life-threatening examples of egregious folly with which we are beset right now, today. These are four ideas that intelligent, credentialed, upstanding, . . . etc., people have saddled us with, four ideas that just about everyone takes for granted.

In all four ongoing cases, a minority of credentialed experts have rebelled against their colleagues and have pointed out that the emperor is stark naked and covered with grease. These classic nude emperors strut with such smug certainty that they are basically caressing shiny quivering bodies to the point of deeply embarrassing obscenity. We’re way beyond walking around in underwear. It’s actually a little gross.

In all four cases we will examine, a majority of respected emperors have shouted down their own colleagues claiming certainty or near-certainty displaying a level of unbridled hubris that makes me happy no lives are at stake. No lives are at stake. And yet sometimes if feels that lives are at stake. The four ongoing cases are all in academia involving research and evidence and knowledge and experience and so forth. All four bits of overstated certainty have become common knowledge to the general public and serve as stark reminders of the power of experts immersed in hierarchies to deceive themselves and us.

In all four cases, credentialed professionals have not only silenced many of their own colleagues who have independently put forth carefully reasoned, evidence-based arguments that in some cases almost reach the level of proof (!) but the naked, shiny people atop professional hierarchies have also been amazingly effective at labeling interesting ideas as “fringe” by engaging in tactics commonly used by schoolyard bullies.

As a result, you have to be pretty open-minded to read this essay especially if you skip past the six already resolved false paradigms which prepare the reader to accept the possibility that usually intelligent authorities can be out of their minds sometimes and can fool a whole world. Propaganda is a powerful thing and it’s not just on the radio.

Now any bright new idea can be made to look interesting and/or plausible so one cannot risk embracing a cool new idea just because it is cool and new and advanced by this or that expert — all fields have their mavericks and they can’t always be taken at face value even if they are credentialed. In the four cases we will examine, it is the mainstream’s response to their rebel colleagues that really opens one’s eyes. When the mainstreamers make the rebels’ arguments for them, one really has to begin to wonder. Indeed, in all four cases it is as if the mainstreamers know deep down that something really is rotten in the state of Denmark.

They seem to know but they just can’t bring themselves to admit it even though in many cases the rebels are merely asking the mainstream to take their own, mainstream, research seriously. It often seems like their shouldn’t be such a bitter controversy at all because there is so much common ground.

One might look at a well-reasoned, evidence-based challenge to conventional wisdom put forward by multiple independent credentialed experts working at accredited institutions all over the world and wonder why the discussion of the issue can’t simply take place in mainstream professional journals. Eventually, a consensus would be reached. Why would the mainstream build walls blockading their own colleagues and then brag about the walls they’ve built?

Sometimes, looking at what the mainstreamers and the rebels say, one wonders what the fight is about. Tradition vs progress? Pride? What’s going on? It’s truly bizarre and this essay won’t answer these questions.

When one reads the mainstream’s responses to their colleagues (who must often create their own minority journals), one might feel a little embarrassed. In some (or all) of these cases, mainstreamers aren’t just naked and covered with oil, they can be seen dancing on tables in crowded restaurants. Now I’m no prude and I think if you want to strip and dance in public, well okay. I don’t care what your body looks like. If you want to have fun and there are no children around, go for it.

But a professional journal seems to me a sacred place like a church or temple or mosque or other place of worship. Does the dancing really have to extend to professional journals? Surely professors who are the keepers of the chalice of rationality can respectfully discuss — with the help of impartial journal editors acting as referees — any topic of interest.

But they can’t and they don’t. And I don’t know why.

I considered “Dancing Naked on a Table in Public” as the title of this book but decided that might be misleading for some readers and deeply disappointing for other readers. So I settled on the less provocative term false paradigm to describe what happens when experts say they are sure of something when really they aren’t at all sure and might well be wrong, when they say they are so sure that they feel justified building walls, and when they brag about the walls they’ve built.

I don’t know if I can convince journal editors to act as impartial referees as opposed to rabid fans. I don’t think I can. I’m hoping to convince students that this should be that case so that when the students become professors and when they have some power, maybe they will insist on open-minded journals as opposed to ones surrounded by walls of pure mindless, status-conscious, knee-jerk drivel.

I should note for the readers benefit that my evident frustration with journals is much more general than personal. I’ve only published one academic paper as sole author and it was accepted just fine by a journal. I explained the Twin Paradox in relativity in an especially simple way and the journal and the referees were fine with it. That same journal then asked me to referee someone else’s paper and I had to recommend rejection because several of the calculations were just plain wrong. I don’t think I had the final say on that particular paper and I don’t know if the author was able to correct his equations and get his work published. I say all this to make it clear that I have no problem with the idea of journals and referees and so forth. My problem is when I read about challenges to conventional wisdom that I would immediately publish if I were a journal editor and I find out there’s a wall.

A perfect example, sort of a zeroth example for us as it is not one of the ten false paradigms we will study in detail, is discussed in a book called Faster Than the Speed of Light written by a physicist working in the highly speculative field of big bang cosmology (how the universe may have begun). He and other physicists independently realized that the speed of light, although it doesn’t seem to evolve or change as time goes on relative to the other physical constants, may have been faster 14 billion years ago when the universe may have looked a lot different from how it looks now.

Actually going faster than the speed of light would be a Kuhnian paradigm shift and would be revolutionary like turning off gravity or controlling the electric force to the point where you could walk through a wall or something absolutely crazy like that. That level of revolution may happen in a hundred years or in a million years when our descendants (if any) will look a lot different from us or it may never happen. But this physicist was just pointing out that we don’t actually know that the physical constants are constant on astronomical timescales and, if the speed of light was faster billions of years ago, that may explain some of the features of our current universe.

I know for a fact that many physicists had this same idea. It is, as the author of the book points out, rather obvious: a fast speed of light makes the universe much more connected, effectively smaller and therefore more homogeneous and this can help a lot with big bang theory. Of course actually creating a detailed theory of a variable speed of light (VSL) is quite difficult and only a handful of people did it.

They were all blockaded by their own colleagues and not because they had their equations wrong but simply because their theory differed from the conventional wisdom which was that the homogeneity of the universe was explained by a rapid expansion of the universe that happened 14 billion years ago called “inflation” which is an ad hoc plausible theory that helps the big bang theorists come out with coherent models but is far from proven.

Nevertheless, it took ten years or more before VSL became the thriving sub-field it is today. Why would professional physicists working in the most speculative area in all of physics stop their colleagues from pursuing interesting new ideas? Was it simply because no physicist had ever tried to discuss the possible evolution of physical constants? Is a physical constant to a narrow-minded physicist like mommy and daddy, always perfect and never changing?

I don’t know what the problem was.

Our goal will be to begin to create a template that will help us identify false paradigms. We will look at six false paradigms of the past — horrific but now resolved though not without great human cost — in order to identify commonalities. What is the fingerprint of a false paradigm?

I must note here that identifying a false paradigm is not the same as proving it wrong. Experts can be absolutely sure of something they have no business being sure of and be right and then smugly say, “I told you so,” even though they were just lucky. Then again, the mainstream, which seems unduly enamored of absolute certainty (let’s face it sometimes a group of mainstreamers all hot and bothered about their precious theory act like teenage boys at a bikini contest disguised wrinkled professors wearing staid ties) seems to crash and burn again and again.

Another important note: false paradigms are NOT the same as Kuhnian paradigms. The paradigms Thomas Kuhn talked about in his famous book and the idea of a paradigm shift are MUCH bigger deals that false paradigms. A false paradigm is simply a dead end that has hobbled a field. It may have killed people. When a false paradigm is finally thrown out, scholars can breathe a sigh of relief and get on with their work; there’s been no breakthrough.

First, creative and clever insults are made almost ubiquitous by a mainstream that becomes dedicated not pursuing reality or humanity or safety or life but to power and control. Anyone can throw around an insult or two when they are arguing a point, but the insults, in the case of a false paradigm, take on a different character. When a false paradigm is holding court, insults are not just primal but primary, they become central to the “argument” made by the ruling class and are repeated again and again like talking points in politics.

Once the credentialed professionals making reasoned arguments about the possibility that maybe their colleagues have been barking up the wrong tree for a long time (or are killing people) have been put in their place by insults, the people who care only about winning the argument throw spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks. They know they can make up nonsense faster than it can be refuted and they use this fact to their advantage. Mainstream arguments supporting false paradigms contain overt circular reasoning, wordplay utterly devoid of logic, and clever zingers presented as if they end all possibility of discussion. Sometimes even utter nonsense is shamelessly stated or put in print and then repeated with straight faces even after it has been embarrassingly refuted.

Again, a real argument might have mistakes in logic or wordplay but in the false paradigm world sometimes the entire argument boils down to “we know we’re right because we’re right and therefore we’re right.”

Insults and nonsense are just the warmup. No theory or knowledge is perfect, so any rebel argument can be attacked on this entirely correct basis. The mainstream, defending a false paradigm that may only have a one percent chance of being true will demand that any alternative theory be proven beyond any doubt whatsoever in order to be published. Sometimes they will say this in writing. The “your theory isn’t perfect” approach is quite powerful because, after all, it is always true — no theory is perfect. This trick is used in politics all the time. No policy is perfect so whoever is pushing the policy can be said to “not care” about the people because this policy will have this or that (very real) negative effect.

Finally, we see in all false paradigms pushed by a terrified mainstream, the ubiquitous plausibility argument. Anything is possible. Any theory might be true. We know our theory is true (circular reasoning) and so this or that problem with it “must be” explainable by this or that possible scenario (plausibility argument). Sometimes the entire mainstream theory is one long possible scenario. If you are in power and in control of professional journals and have a death grip on professional and public opinion, all you have to do is create a “must be the case” scenario in which your theory is true and then that’s it, you’re done and you can go home and continue your work whilst ignoring the useless theory you are defending to your dying day.

Even before looking at what mainstream false paradigm warriors say, a failed idea can be identified by one or more of the following four precursors. First, a false paradigm may be strongly touted but not actually used in practice. Second, false paradigms often require constant extreme adjustment to fit new facts. Third, false paradigms can’t tolerate challenge; dissent must be squashed, sometimes viciously. Finally, if a reversal of the hierarchy dooms an idea, it may be a false paradigm.

Suppose your teacher is boarding a space shuttle. Suppose you are told that the engineers who are asked to sign off on the safety of the launch have unanimously said, “No way can we launch today because, under the present circumstances, the launch is a live-or-die coin toss for which the astronauts did not sign up; if we launch, heads says all is well, tails says the shuttle explodes takeoff so we need to postpone the launch.”

Those weren’t the exact words of the engineers. We will quote them precisely below. But they said words to that effect. No sane person would launch. You would not. I would not. Christ McAuliffe’s students would not. The fact that building space shuttles is rocket science is irrelevant: the launch-or-don’t-launch decision process is NOT rocket science. Anyone can see that the engineers should be listened to.