Shakespeare Again

He was the most well-read man in England with a vocabulary that dwarfed that of even other professional writers. But, so far as anyone knows, he didn’t own any books or write any letters. He had two daughters who never learned to read or even write their names presumably because they grew up raised by their illiterate mother in their bookless house while daddy William went to London, two days’ ride from his native Stratford and, to paraphrase Bloom, “invented humanity” through his characters’ theretofore unheard-of introspection. Meanwhile his family remained in his home town, fed and housed, but starved of the intellectual stimulation that animated their illustrious relative.

This great genius of humble origins spent time in both London and Stratford during a 20-year period starting in the early 1590’s. He was associated with a London acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (aka the King’s Men), as an actor (1595) and later as an investor (1603). Presumably, he wrote the plays that bear his name and earned money from the performances although there is no direct evidence for any payments made to Shakespeare for plays or manuscripts.

The Blackfriars Theater today. Shakespeare of Stratford was an investor/partner as of 1608.

The problem is, the man with the right name and the connection with the actors left no other trace of his writing career except for the bylines. No one ever claimed to have met the great author, Shakespeare. The people who published his plays and poems left nothing: they didn’t record payments to him, no autographed books remain, his publishers didn’t send Shakespeare letters or receive letters from him; they didn’t even write to their friends about him, as far as anyone knows. Shakespeare was the greatest writer in England, but seemed to be nobody in particular at the same time. Even in his home town of Stratford, no one seemed to know he was a celebrity; they wrote about him, but not about his famous works.

According to Diana Price, during Shakespeare’s lifetime, about seventy documents connected to Shakespeare the man were produced and still survive. They show Shakespeare was an actor and theater investor; two say he was a tax dodger; one that he was a grain hoarder; another claims he was dangerously violent; none mention writing.

By way of comparison, Price collected data for twenty-four other, less famous, Elizabethan writers: Jonson, Nashe, Massinger, Spenser, Daniel, Peele, Drayton, Chapman, Drummond, Mundy, Marston, Middleton, Lyly, Heywood, Lodge, Greene, Dekker, Watson, Marlowe, Beaumont, Fletcher, Kyd, and Webster.

Every writer Price looked at penned letters or wrote inscriptions in books or received payments for writing or left behind manuscripts or was mentioned as a writer by people who knew him personally. Most left behind several pieces of evidence connecting them personally to their craft. Ben Jonson is at the top of the heap in this respect: he left behind a personal library of more than 100 books, a handwritten manuscript, numerous letters, more than a dozen records of payments for his writing, as well as several inscriptions in gifted copies of his books. Shakespeare, despite the fact that he left behind more documents than anyone except Jonson, left us nothing about writing.

By my count, using data from Price’s book, for a typical Elizabethan writer, roughly half of the suviving personal documents from his lifetime would be expected to be directly related to vocation, to writing. That means for Shakespeare, we happened to go seventy-for-seventy documents NOT related to his status as the greatest writer in England which, from a probabilistic perspective, is the same as flipping seventy tails in a row. The odds are approximately 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 to 1 against.

How long would a take a large team of monkeys typing randomly to accidentally create all of Shakespeare down to the last comma? A long time.

But it could happen. You can actually have a decent chance of flipping 70 tails in a row, if you are willing to flip coins continuously for 400 trillion years which is about 30,000 times the age of the universe if you believe current estimates. That is, if you had been flipping coins constantly since the time the universe began, your chances of having succeeded by now would be microscopic. There is good news however: you’ll most likely flip your 70 tails long before the monkeys finish typing Shakespeare!

But seriously, what the calculation above means is that if you (1) believe the 50% expected to be writing-related statistic and if you (2) don’t count acting as writing-related and if you (3) don’t count documents produced after death, then, statistically speaking, you can take it as proved that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare.

I do not consider the above an especially strong argument because there are too many ifs needed to make it work. Still, it is an interesting way to try to get our minds around the authorship issue.

Samuel Clemens argued fiercely that the apparent lack of a personal connection with the literary world in London was absurd if Shakespeare was the most famous writer in the country. When Shakespeare of Stratford died in 1616, no one noticed: there was no funeral, no burial in Westminster Abbey, not so much as a whisper of mourning for the greatest writer in the English language who had ever lived. There was just a long, detailed will that didn’t mention a single book.

“He is a brontosaur: nine bones and six hundred barrels of plaster of Paris. . . We are The Reasoning Race and when we find a vague file of chipmunk-tracks stringing through the dust of Stratford village, we know by our reasoning powers that Hercules has been along there.”

Shakespeare’s gravestone. Where were the lamenting poems, eulogies, and national tears, Clemens says. Spenser, Jonson, Bacon, and Raleigh generated big responses when they died, he points out. Why didn’t Shakespeare?

Mr. Twain/Clemens puts some actual Shakespeare next to what is on the gravestone. This is a wonderful illustration of the difference between poetry and doggerel and is a slap in the face if you believe, as Twain does, that Shakespeare himself composed the lines on his gravestone. Why would the greatest poet ever put garbage on his gravestone? Maybe he thought it would be funny.

I agree with Mark Twain. Shakespeare of Stratford the writer of crude doggerel was one person and Shakespeare the author, the man with inside information about Queen Elizabeth’s court, was someone else. However, it wasn’t Twain’s arguments that convinced me, or for that matter, the “inside baseball” argument.

Diana Price makes the “Where are the records?” argument as well as it can be made and I do think my “statistical impossibility” argument inspired by her work is cute. But these arguments don’t convince me either.

Sir Derek Jakobi and Mark Rylance, the noted Shakespearean actors, also have their doubts about authorship. They made a video that is worth watching just to get a feel for what these two brave souls are up against. They don’t go into much detail in this brief discussion, but they do hit some key points.

Sir Derek and Mark: “None of our critics have done much more than try to attack our character. . . We are trying to counter what we consider a myth, a legend. The normal reaction that anyone who offers this alternative gets is insult, vituperation, NEVER discussion.”

As these two renowned actors explain, experts in the field, such as the eminent James Shapiro at Columbia University, routinely say there is nothing to discuss, that we should not study the authorship question at all because it is such nonsense. Ironically, this is a particularly convincing argument that, in fact, Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare.

For example, Shapiro argues that Shakespeare’s death actually WAS noticed. He explains that seven years after Shakespeare of Stratford died, the First Folio was published and this should be considered a response to his death.

Sputtering arguments like Shapiro’s and desperately nonsensical commentary saying that, for example, Polonius in Hamlet is not a viciously accurate caricature of the great Lord Burghley even though the connection was noted 150 years ago, are every bit as good and twice as funny as “Blest be ye man that spares these stones.” Sometimes I think Shapiro and his ilk know perfectly well what the truth is, but are hoping you never do.

This reminds me of a famous (probably apocryphal) story about evolution.

From “Origins” by Louis Leakey and Roger Lewin.

Just keeping it quiet is one way to deal with it.

Shakespeare’s works indicate that the was as steeped in the art of falconry as Clemens was in the culture of riverboats. The plays were clearly written by a nobleman for commoners did not practice falconry. Nor did they travel in Italy.

Still, the plays are fiction and one must be careful using fiction for biography. So even this argument doesn’t convince me. So far the most convincing argument is that the experts gibber.

And then there’s the sonnets.

Almost everyone I’ve ever spoken to about Shakespeare sees, regards, and understands the sonnets simply as wondrous poems that Shakespeare wrote. This is the truth, but not the whole truth. The sonnets were written in the first person, addressed to a young man, covered personal matters, and discussed real events that took place in the early 1590’s through the early 1600’s.

“Shall I compare thee to a Summer’s day” was written to a particular (real) young man. Wordsworth famously wrote of the sonnets, “with this key, Shakespeare unlocked his heart.” But actually, he unlocked a great deal of plain old biography too.

A letter from Shakespeare to a youth whom he loved and whom he wishes to immortalize: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, so long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

This particular sonnet doesn’t tell us much, just that the author loved the person he was writing to and had the idea that his love would live forever in the “eternal lines” of great poetry. Shapiro and others are fond of ignoring the sonnets or claiming that they are impersonal (!), but we thinkers must keep one thing clear in our minds: the sonnets are letters.

By 1598, a dozen or so Shakespeare plays and poems had been published; the name Shakespeare was famous. The sonnets/letters had NOT been published. That year, a man named Meres praised the author’s writing generally saying, among other things, “witness his sugar’d sonnets among his private friends.” This is the first known reference and it is crucial: the sonnets were kept private.

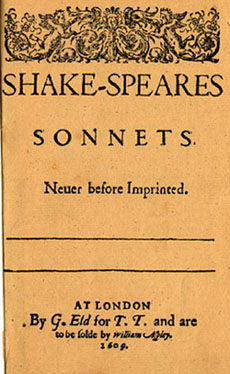

They remained so until Thomas Thorpe published SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS in 1609. The author clearly ntended for the sonnets to be published. They were to be a “monument” to the beloved young Earl to whom he had dedicated his two epic poems, a way to grant him immortality. The author of the sonnets represents himself quite clearly as an older fellow-nobleman.

In what follows, we will simply read the sonnets as written. No code-breaking is required. We will ignore the (absurd) mainstream idea that perhaps the most deeply personal series of poems ever written, was not personal.

These sonnets were kept private until 1609.

Shakespeare’s “lovely boy” was a young earl to whom he offered, through the sonnets, guidance, support, and unconditional love.

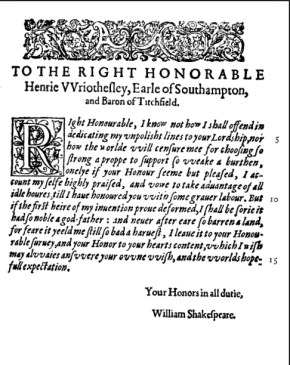

1593. First epic poem. The “all happiness” phrase reappears in the publisher’s dedication in the sonnets. This is the first appearance of the Shakespeare byline.

1594. Second epic poems. No codebreaking is needed. Shakespeare was very close to this Earl. No one else has the honor of a Shakespeare dedication.

Shakespeare, whoever he really was, begins his letters to the teenaged Earl by calling him a “tender churl” as he admonishes the high-born young man not to waste his “content.” Later, he chronicles the Earl’s life including his death sentence for treason and his amazing release from the Tower after the Queen’s death. Finally, this older man who loved Southampton so dearly signs off in the 126th sonnet with an emotional farewell that opens with “O thou my lovely boy . . .” and closes with a warning about the inevitability of death.

Already, there’s major trouble for the traditional attribution. There’s no evidence Shakespeare of Stratford ever so much as met Southampton, much less knew him intimately enough to call him “tender churl” or “my lovely boy.”

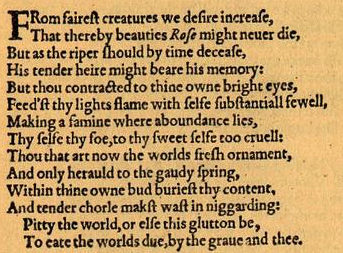

First sonnet: “From fairest creatures we desire increase.” Don’t bury your “content,” don’t be wasteful, “tender churl.” You, my young man, have reached the time in your life when we expect great things, not least of which is an heir. Don’t “make a famine where abundance lies.”

The Earl of Southampton faced heavy pressure to marry in the early 1590’s; he ultimately refused and was fined by his guardian, Lord Burghley.

No commoner could say this to any earl.

Second sonnet: “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow,” you’ll understand how important it is to have children. When you are old you’ll want children so you can be “new made when thou art old and see thy blood warm when thou feel’st it cold.”

In theory you can write this as a personal letter in your twenties to a teenage Earl who you think should get married. In reality, probably not.

Third sonnet: Shakespeare shares nostalgic memories of the boy’s beautiful mother: “Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee calls back the lovely April of her prime.”

Shakespeare of Stratford did not have the opportunity to meet the Earl of Southampton’s mother in the lovely April of her prime or at any other time. He showed up in London for the first time when Southampton was already a teenager and probably never met him or his mother.

Sonnet 22: “My glass shall not persuade me I am old, so long as youth and thou are of one date.”

Whoever Shakespeare was, he strongly identified with the Earl to the point where one suspects a familial connection.

Sonnet 73: “That time of year thou may’st in me behold, when yellow leaves or none or few do hang, upon those boughs which shake against the cold, bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang . . .”

Again, the writer is overtly representing himself as a generation removed from Southampton.

Sonnet 126: “O thou my lovely boy,” beware of “nature” and of “time’s fickle glass.” “Fear her” and remember that “her audit (though delayed) answered must be.”

The Earl of Southampton was not Shakespeare of Stratford’s “lovely boy.” No way. Sorry, Professor.

The writer of the sonnets so far seems to be an older peer of Southampton, a fellow nobleman who can give his lovely boy advice. We have our suspicions at this point, but we don’t really know. We don’t know, that is, until we read Sonnet 125.

Here, the author directly states that he is, in fact, nobility. He writes, “Were it aught to me I bore the canopy with my extern the outward honoring . . . ” A commoner could not have sensibly written any such thing.

ONLY nobility bears a canopy in a royal procession.

This is a near-disaster for the mainstream, almost a coup de grâce to the traditional theory. If you bore the canopy during a royal procession, but your true loyalties lie elsewhere, with Southampton, you are most certainly NOT a commoner from Stratford. You are what you have been representing yourself as for 124 personal, private letters: an older nobleman closely allied with Southampton.

But maybe we’re misinterpreting the reference to bearing the canopy. Maybe a commoner was just imagining how it would be if he were to bear the canopy. After all, he said, “Were it aught to me . . .” So maybe it was hypothetical.

Fine and dandy. Desperate in my opinion, but fine and dandy. You’ve yet to be convinced, but perhaps your mind is open, perhaps you will admit a sliver of doubt tickling your skeptical mind. Let us keep reading.

As far as the mainstream theory is concerned, we’ve gone from “not so great” after reading the first three sonnets to “Houston we have a problem” after reading the aging sonnets all the way to “uh-oh” upon seeing the canopy sonnet.

But it could still be Much Ado About Nothing.

Next stop: catastrophe.

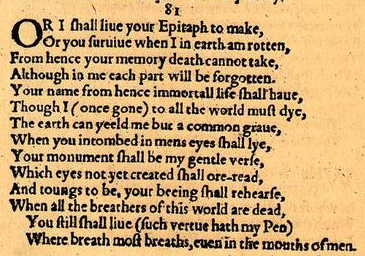

The great author brimmed with confidence that his letters to Southampton would ultimately take their place amongst the greatest writing of all time. He said his sonnets would outlast “tyrant’s crests” and “tombs of brass.” Not having any truck with modesty, he declared, simply, “such virtue hath my pen.”

As the sonnets flowed from the genius’s pen, the epic poems, dedicated to Southampton, had been printed and reprinted, the plays had become popular, and the name Shakespeare was famous. “Your monument shall be my gentle verse, which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read . . .”

“Your name from hence immortal life shall have . . .”

“. . . Though I (once gone) to all the world must die.”

If he had written, “I am using a pseudonym” I’m sure Professor Shapiro would find a reason to ignore the line.

Smoking gun in Sonnet 81. (Be nice. Don’t say, “Thor Klamet, I’ve read Shakespeare and you are no Shakespeare.” A rhyme’s a rhyme and will be for all time.)

Even this doesn’t give the mainstream pause. It’s as if a tornado has just blown your house away and you are smiling and saying everything is fine. I might admire your sense of perspective though I’d be concerned about your sanity.

We have now pretty well shot down the traditional theory that some young commoner who apparently never met Southampton was absolutely, positively Shakespeare. The author went so far as to state outright in a personal letter that he was writing under a pseudonym!

Even so, maybe we’ve misinterpreted everything. Maybe, a 20-something commoner writing under his own name wrote to his friend Southampton and we’re guilty of code-breaking and over-interpretation to fit a predetermined conclusion. “Though I (once gone) to all the world must die” might mean, “I’m just a lowly author and a commoner, who cares about me, you’re the subject of these lines, a great Earl, you will be remembered, the writer is nothing, a mere afterthought, especially a commoner like me. I’m famous now, yes, but it won’t last.”

After all, the next two lines say, “The earth can yield me but a common grave, When you entombed in men’s eyes shall lie.” Maybe he’s just saying he’s a commoner.

And he didn’t actually, literally, say, “I am writing under a pseudonym.” So you still have a right to be skeptical. If you are so, then good for you. After all, if the Shakespeare thing is true, it’s the greatest hoax ever perpetrated, so it is proper to demand overwhelming evidence.

Doubts aside, it does begin to feel a little like beating a dead horse at this point. There are no books, letters, or manuscripts, no personal literary contacts, even his neighbors in his home town knew nothing, his own children couldn’t read his work; the actual writer was a man steeped in falconry who could write personal admonishments to a young earl, who represented himself as a middle-aged nobleman; even though he said his writing was so great it would last forever and even though he knew the name Shakespeare was already famous, he nevertheless implied his name would be lost to history.

Your name from hence immortal life shall have, Though I (once gone) to all the world must die.

It could be confimation bias causing me to see these lines as a smoking gun, but honestly, I don’t think the horse is even quivering at this point. But we will press on just the same. In fact, what we will do is shoot the already-dead horse one last time. There is another bullet in our smoking gun for you hard-core skeptics.

When the sonnets were finally published, the lucky publisher included a dedication wishing Southampton the same “all happinesse” Shakespeare had wished him in one of the epic poem dedications as well as the same “eternitie” the sonnets themselves were promising.

“All happiness” echoes the 1594 dedication to Southampton

Like “all happinesse” and “that eternitie,” the “our ever-living poet” phrase is, appropriately, Shakespeare, Shakespeare, Shakespeare.

Here is a Shakespearean eulogy: “. . . our scarce-cold conqueror, that ever-living man of memory, Henry the fifth. . .” intoned over the dead body of the former King in Henry VI Part 1, Act 4, Scene 2 (First Folio version).

Again, I’m sorry, but that’s that. It’s a eulogy. Shakespeare the commoner was still living in London in 1609; he moved back to Stratford the next year and did eventually die, but not for another six years. Thomas Thorpe was a contemporary observer in a position to know. He held the original sonnets in his hands. He could not have been mistaken about whether the author was still alive and his Shakespearean eulogy could not be more clear.

The only way out is to argue that “ever-living poet” isn’t a eulogy and I wouldn’t want to have to make that argument. So I feel for the mainstream, I really do.

The gun smokes anew, the body of the horse begins to decay, and the mainstream thinks it’s still mounted in the saddle galloping along with the wind in its hair.

Nevertheless, you can hold your nose and ignore the decaying horse and argue that “ever-living poet” might not be the eulogy it appears to be. You can note that Southampton’s initials were H. W., not W. H., and that as an Earl, Henry Wriothesley should not be addressed as “Mr.”

Or, you can argue that even if the sonnets were personal, they weren’t necessarily personal to Shakespeare. Maybe they were commissioned by an older nobleman who was close to Southampton. Maybe Shakespeare was writing about someone else’s pathos. All or any of this is possible.

These arguments should be, nay, must be, made. But that’s not what the ivy league professors say. They say there is no issue at all. They have certainty. The professor doth protest too much, methinks.

In Hamlet, Gertrude, watching the play within a play, is uncomfortable because the character of the Queen says she will never remarry, no matter what. “The lady doth protest too much, methinks,” says Gertrude, squirming.

If (1) Shakespeare was, in fact, forty when he wrote “when forty winters shall beseige thy brow,” if (2) he knew Southampton’s mother personally in the “lovely April of her prime,” if (3) he ever actually “bore the canopy,” if (4) he truly believed his name would be lost to history when he lamented, “though I (once gone) to all the world must die” OR if (5) Thomas Thorpe meant “our ever-living poet” as a eulogy, if any ONE of these things is true, then Shakespeare of Stratford didn’t write Shakespeare.

I believe Shakespeare was the age he represented himself to be in his sonnets, I believe he knew Southampton’s mother before the boy was born, I believe he did bear a canopy in a procession after the Queen’s death, I believe he thought his incomparable poetry would last forever but his name would be lost, and I believe an ever-living poet is a dead poet. The sonnets don’t make sense twisted into some kind of impersonal wordplay “ever-living poet” isn’t just any eulogy, it’s a Shakespearean eulogy.

We are human, we understand context. The sonnets have context. The writer said he was a fellow nobleman, a generation removed from the lovely boy. Why should we not believe him? If his own testimony is untrue, there is no context and if there is no context, there is no humanity.

“He was a genius” doesn’t explain away context. It is likewise inconceivable to me that the sonnets were written for someone else, i.e., that they were commissioned, someone else’s pathos. So I’m stuck with Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare. As unlikely as it sounds, I’m stuck with it.

But if Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare, he was set up as the apparent author. Why do that?

Monument to Shakespeare in Stratford built within a few years of his death. “The judgment of Nestor, the genius of Socrates, the art of Virgil. The earth encloses, the people sorrow, Olympus posseses. Stay passenger, why goest thou by so fast? Read if thou canst whom envious death hath placed within this monument — Shakspeare: with whom quick nature died whose name doth deck this tomb far more than cost since all he hath writ leaves living art but page to serve his wit.” Whatever that means.

Why have a conspiracy to make it look like Shakespeare the illiterate commoner was Shakespeare the great author? Why hide the real author? Why weren’t the sonnets published sooner with a direct connection to Southampton and with the real author’s name? For that matter, why not include the sonnets in 1623 when all the plays were compiled into the famous First Folio when the number of published plays was doubled at a stroke? Where did all those unpublished plays even come from? Why would Queen Elizabeth and King James go to so much trouble to hide the true author and make it look like it was Shakespeare of Stratford? How did the whole thing even get started?

Was Shake-Speare chosen as a pseudonym to match the name of an obscure actor and confuse everyone or was it a coincidence that someone had a name to match the pseudonym? Was there some advantage to using a front-man instead of an ordinary pseudonym?

Some time after Shakespeare died in Stratford in his bookless house, a monument was erected implying he was a great thinker; it makes an interesting brother to the gravestone with the doggerel that Mark Twain made fun of. Shakespeare’s Stratford origins were alluded to in the preface to the First Folio written by Ben Jonson in 1623. These bits of hard evidence setting up Shakespeare of Stratford as both an actor and great author for the first time, years after his death, were, conspiracy theorists say, the beginning of the great hoax.

Shakespeare’s Stratford home called New Place where he retired. He died there in 1616. His three-page will meticulously distributed his belongings. No books were mentioned.

But why? What was going on? We read the sonnets as written, fine. We become suspicious, fine. But then what of the post-death alleged conspiracy — the monument and the preface to the First Folio? What the Hell?

The outline of an answer is easy enough to sketch though far from definitive. Shakespeare’s dedicatee from the two epic poems, Southampton, was a controversial figure as you already know. But you may not know the half of it.

The young woman the young man was implored to marry in those first sonnets happened to be Lord Burghley’s grand-daughter: the great Lord had commanded this marriage take place. Since Burghley was the Queen’s closest advisor and the most powerful man in England, his grandchild wasn’t someone you refused lightly.

The great Lord Burghley. If given the opportunity to marry his grand-daughter, say YES.

Shakespeare told the young man, “From fairest creatures we desire increase, that thereby beauty’s Rose might never die” and then went on for 16 more sonnets imploring the stubborn Earl, his tender churl, to marry Burghley’s grand-daughter and make an heir. It did no good. Marrying into Burghley’s family would have increased the scope of Southampton’s powers greatly. He was a fool to refuse, but refuse he did. We don’t know why.

The word “Rose” in the second line of the first sonnet quoted above was mysteriously capitalized and italicized in the original publication just as it is here. No one knows why.

Ten years or so after the stubborn Earl refused to become a member of Burghley’s family, the Queen lay dying. Southampton, now a strapping 20-something, and his ally, the popular Earl of Essex, and a dozen or more men now attempted to gain access to the expiring Queen. The Tudor Rose dynasty seemed to be coming to an abrupt end. Elizabeth had no acknowledged children. No historian believes the flirtatious Queen was actually a virgin and it is considered quite possible that she had one or two illegitimate children, but these bastard offspring, if they existed, would not have been eligible to inherit the throne, not without a lot of powerful backing. As things stood in 1601, there would be no continuation of the Tudor bloodline and there was no clear succession. The uncertainty was frightening for much of the public throughout Elizabethan England.

The two Earls seemed to have good timing although it is by no means clear what they intended to do once they gained access to her majesty’s bedchamber. Presumably, they had a plan to try to control the succession. It didn’t matter, because Essex and Southampton were in over their fool heads. Fools and their heads are soon parted, as you know.

The Tower of London today. Earth to Southampton: Marry the grand-daughter; messing with Lord Burghley is NOT healthy.

Burghley, who had been secretly planning the succession for years, outsmarted the Southampton-Essex amateur hour and had them and their lot arrested and tried for treason. All were convicted of course, the outcome of the trial never being in doubt. Essex, despite his popularity, had his date with the axeman, though it was a little on the brief side as dates go. Some lower-ranking members of the conspiracy did not fare so well as the pretty young Earl: they were tortured to death.

But not Southampton. He was sentenced to die and watched his friend die, but, as he waited fretfully in the Tower of London, his sentence was mysteriously commuted to life in prison. There is no formal record of the legal proceeding that allowed this extraordinary thing to happen, but it did happen. No one knows how or why.

The Second Earl of Essex didn’t make it past 35 years of age. Many thought his sentence would be commuted. His head rolled despite his popularity. Burghley is the WRONG person to mess with.

The sonnet-writer was chronicling these events and may have had inside information. Sonnet 87 has both a happy and resigned tone as if a big decision has been made. It says to Southampton, “The charter of thy worth gives thee releasing” which could mean a lot of things. In the same sonnet, we are told of a “great gift upon misprision growing” and we find out that this gift “comes home again on better judgment making.”

What is being released? What is the charter of Southampton’s worth? Why the legal term, misprision? What was the better judgment?

Misprision of treason means you knew about treason, but didn’t report it. This is a legal term that was common in Elizabethan times. Misprision of treason was a crime, but not a capital crime. If you love Southampton, this is obviously a “better judgment” than plain old treason. Something about Southampton’s “worth” may have led Queen Elizabeth to spare the young fool.

Maybe. This sonnet is not nearly as direct or clear as “Though I (once gone) to all the world must die.” All we know for certain is that Southampton was not executed.

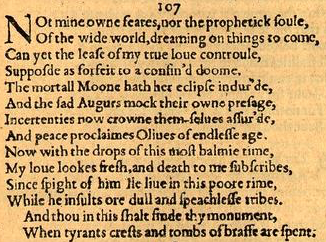

Southampton was not only not executed, the convicted traitor was in fact released after the Queen died. As soon as King James I had safely ascended the throne, Southampton felt the warmth of the sun on his face. Shakespeare, or rather the actual author, who we can now surmise cannot possibly be the young commoner named Shakespeare, celebrates this event in the famously ebullient Sonnet 107, the poem most clearly linked to Southhampton, not only by crazy conspiracy theorists, but also by mainstream scholars for centuries.

After the “mortal moon” (Elizabeth) suffers her “eclipse” (death), Shakespeare’s “true love” who was “supposed as forfeit to a confined doom” in the Tower now “looks fresh” as “peace proclaims olives of endless age” (James has peacefully acended the throne) and the “sad augurs mock their own presage” (people who predicted a civil war now look silly).

Whoever wrote this was pretty happy about the turn politics had taken. Meanwhile, Southampton began his second chance at life though without his great friend Essex.

Burghley wanted it to be King James so it was King James. He peacefully ascended the throne in 1603. Southampton was then released from the Tower.

Some people think Southampton’s idea that he could control the succession together with the mysterious pardon plus Shakespeare’s enigmatic mention of “beauty’s Rose,” make everything perfectly clear: Southampton was obviously Elizabeth’s son, a possible heir to the Tudor Rose dynasty if he were ever acknowledged. If he had married Burghley’s grand-daughter, beauty’s Rose might indeed never have died.

According to this theory, Southampton had refused to marry Burghley’s grand-daughter, so he didn’t have the great man behind the idea of continuing the Tudor Rose dynasty; meanwhile, Elizabeth, for her part, wasn’t keen on dropping the virgin Queen thing, acknowledging Southampton as her son, and letting him become King. On the other hand, she wasn’t going to kill her own son even though he had been convicted of treason. This is called the “Prince Tudor” theory.

Queen Elizabeth I. She had no acknowledged children. The Tudor Rose dynasty ended with her. Of course, she was not a virgin; she had sex AND retained power.

Queen Elizabeth II in the lovely April of her prime 340 years after the death of Elizabeth I.

If Southampton was really Elizabeth’s biological son — he wound up in the royal household because his supposed father died when he was very young — it would explain the fact that he committed treason but lived past 30 anyway and would also explain why he thought he could get away with trying to barge into the Queen’s bedchamber with armed men. It would also explain why the sonnets were too hot to handle — if they told of a possible heir to the throne, they were political dynamite.

Without exhuming bodies and doing DNA tests, we will never know the ins and outs of the succession battle that took place in the early 1600’s. All we really know is that Essex didn’t fare very well. We also know that Burghley was not to be trifled with.

The craziness of the Prince Tudor theory drags us in like a siren, beckoning, offering more goodies. Crazy begets crazier. Hold on to your hat.

The father of the girl Southampton was supposed to marry, Edward de Vere, may be the most likely writer of the sonnets if you believe the Prince Tudor theory. He was a brilliant and dashing nobleman and happened to be one of the Queen’s lovers (contemporary eyewitness account) AND had married Burghley’s daughter. If he was also Southampton’s father, then the plot thickens considerably and the context of the sonnets begins to make sense.

The boy was being asked to marry his half-sister. This could explain his refusal.

Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford, the highest ranking earl in Elizabethan England. Burghley’s son-in-law, the Queen’s lover. Was he also Shakespeare? Was he also Southampton’s father?

But could Edward de Vere really be Shakespeare? In a word, yes. One connection is the First Folio. In 1623, only 18 plays had ever been published. A big part of the canon, including many of the most important plays, existed only in manuscript never having seen print. Suddenly, the First Folio, a massive project, appears, beautifully printed. Now there are 36 plays, preserved for posterity. How was this accomplished?

Well, the First Folio was dedicated to the Earl of Montgomery, who just happened to be married to Edward de Vere’s daughter. Montgomery probably bankrolled the project (hence the dedication) while his wife, Oxford’s daughter, presumably supplied the manuscripts. This is the same daughter who was supposed to marry Southampton in the early 1590’s, the same daughter whose hypothetical hand was presented so beautifully in the first 17 sonnets, the “marriage sonnets” as they are still called today.

The connections continue. Oxford’s brother-in-law visited Denmark and the court at Elsinore for six months in 1581-1582 and produced a handwritten, unpublished document upon his return to England. The document mentioned two courtiers, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Of course, that could just be a coincidence.

Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford is the reason traditional scholars have to embarrass themselves trying to argue Polonius is not a caricature of Burghley. The relationship and the animosity between Polonius and Hamlet is an almost perfect parallel to the historical conflict between Burghley and Oxford. The minute you admit Polonius is Burghley and accept Oxford as an authorship candidate, the autobiographical nature of Hamlet becomes virtually impossible to refute. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are the tip of the iceberg. And that’s just the one play.

Oxford was known as incomparably brilliant and received during his whole life an unprecedented 1000 pound yearly stipend from the Queen that was continued by King James. There was no official reason for the stipend. Think about that. Meanwhile, here are some signatures to ponder.

As countless non-mainstream academics and reputable intellectual leaders in many areas, even including the living descendant of the great Lord Burghley himself, regularly point out, the sonnets and other evidence create an eminently reasonable case that Shakespeare of Stratford may have been cast by the powers that were (Elizabeth, Burghley, James) as a front-man in perhaps the greatest and most successful hoax of all time.

The Prince Tudor – Edward de Vere theory is another matter, of course.

If Shakespeare was really Edward de Vere and if he was really Southampton’s father and if Southampton was really the last member of the Tudor Rose dynasty, then Sonnet 33 is pregnant with meaning, literally.

When Shakespeare says, “Even so my Sun one early morn did shine, With all triumphant splendor on my brow, But out alack he was but one hour mine . . . ” what is he talking about? The weather?

Who was “Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace”? Was it the s-u-n sun setting? Or was it the Queen herself of necessity hiding her belly full with Edward de Vere’s bastard s-o-n son.

According to this admittedly cryptographic analysis, Edward de Vere got to hold his son, who would become the Earl of Southampton, for just one hour before the “region cloud” (the Queen) “hath masked him from me now” (took him away).

Code-breaking, of course, is not especially reliable. Still, if you decide Southampton was probably the Queen’s son, it fits perfectly to make Edward de Vere his father and author of the sonnets. So “O thou my lovely boy . . . ” would be taken as from father to son. The sonnets, then, would be a monument written by the Earl of Oxford, the Queen’s former lover, to his son who might have become King and elevated the brilliant spendthrift Oxford to royalty in the eyes of history.

This is the full crazy theory. It is built out of “beauty’s Rose” in the first sonnet (code-breaking) and “Sunne” in the 33rd sonnet (more code-breaking). Though the code-breaking embellishments must be regarded as questionable, the foundation is reasonably solid: (1) Shakespeare does appear to be a pseudonym for an older nobleman very close to Southampton (sonnets); (2) Southampton did try to control the successsion and was spared despite being convicted of treason (historical fact); (3) the Queen did have an affair with Edward de Vere (contemporary eyewitness).

For all of this to really hold together, the biography of Edward de Vere would have to fit with the plays and poems. The appearance of the names Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as a pair in de Vere’s life is my favorite connection in this regard and is, in fact, merely the tip of the iceberg. A number of biographies of the Earl of Oxford have been written at this point and the relationship between his life and the plays is nothing short of astounding.

Elsinore, a real place where Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, real people, were met with Edward de Vere’s brother in law, a Baron named Peregrine Bertie. Bertie married Lady Mary, Oxford’s sister, and took her to the country where the two reportedly drank heavily and argued ferociously (letters exchanged amongst a number of eyewitnesses). Sound familiar?

Rylance and Jakobi note wryly that the connection is so strong that whoever wrote the plays had to have known all about Oxford’s life.

Another example: Oxford at age 30 got Anne Vavasour, one of the Queen’s nubile ladies-in-waiting, pregnant at age 18. The Queen chucked them both into the Tower (along with the infant!) for this transgression. Vavasour’s and Oxford’s people fought in the streets as a result of all of this and the battles were finally stopped by the Queen a la Romeo and Juliet.

The Birmingham Royal Ballet presents the Montagues and the Capulets fighting it out in the street in a presentation of Romeo and Juliet. Anne Vavasour’s uncle Thomas Knyvet’s servants and the Earl of Oxford’s men spilled real blood on the streets of London in 1581.

The connections between Oxford and the plays go on and on and on (and on). I would say the case has been made by the Oxford partisans incredibly convincingly. They may even have proved it by now; I don’t know enough to say precisely how convincing it is, only that it has convinced me.

I have never seen an argument for ignoring the sonnets worth repeating. The best I’ve seen is that the sonnets may possibly have been commissioned and this would explain them. But there is not one tiny shred of evidence that the sonnets were commissioned. Ignoring the sonnets altogether qualifies as irrational. If they weren’t commissioned they are a strong indication of pseudonym.

Edward de Vere was probably Shakespeare. If so, there is an uncomfortably high probability that he and Queen Elizabeth were the parents of Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. It would explain a great deal and is plausible given that he and the Queen were referred to as lovers by a contemporary observer. If you include Southampton’s ill-fated attempt to control the succession and his pardon for treason, it actually hangs together rather well.

Great blog! The mystery continues: