A Rational Person Reads Shakespeare (Sonnets, Origin Story)

Thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remembered not to be,

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

It was 1590 and time for the teenaged Earl of Southampton to get married and create for the world a worthy heir. The golden good looks the boy inherited from his mother were, insisted Shakespeare, some waiting baby’s birthright.

The young earl, Henry Wriothesley (RYE-zlee), begged to differ.

No one knows how William Shakespeare got involved in the attempt by Henry’s elders to convince him to marry a particular young woman, but the six lines above and sixteen of the first seventeen sonnets — often called the “Marriage Sonnets” — begged the recalcitrant earl to marry and (more importantly) to produce a male heir.

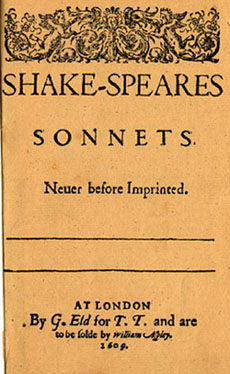

Begun in the early 1590’s, the sonnets weren’t published until 1609.

So “Marriage Sonnets” isn’t quite the right name. In sixteen sonnets, Shakespeare finds sixteen ways to refer to Southampton’s potential progeny: tender heir, fair child, thine image, acceptable audit, flowers distilled, beauty’s treasure, new-appearing sight, concord of well-tuned sounds [as in a harmonious family life], form of thee, another self, copy, breed, sweet issue, truth and beauty [as in “Thy end is Truthes and Beauties doome and date”], living flowers, and, finally, some child of yours. In sixteen “Make-Us-A-Baby Sonnets,” marriage is nothing more than a means to an end.

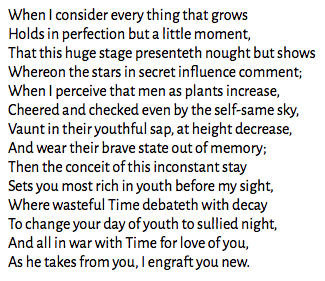

Sonnet 15 is an important outlier, being the only one of the first seventeen that refrains from shouting the joys of fatherhood from rooftops: this sonnet offers eternity in another form. Shakespeare says his immortal words will refresh Southampton’s “youthful sap” despite the “decay” perpetrated by “wasteful Time.”

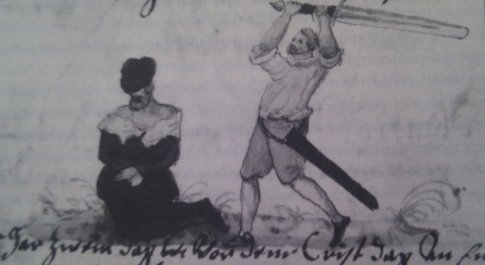

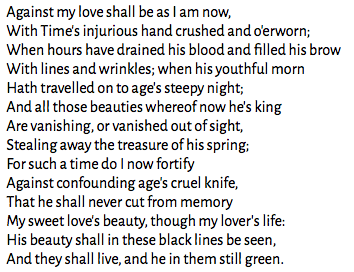

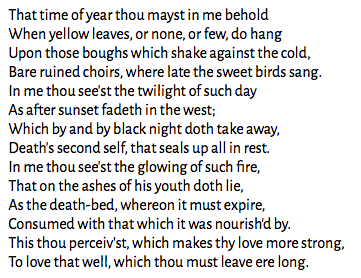

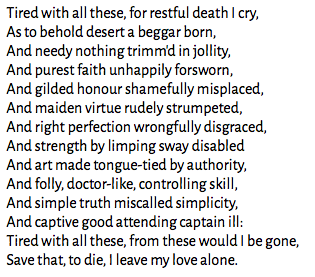

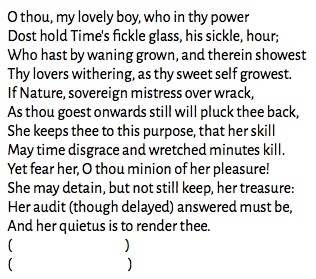

At length, this becomes the central theme of the entire one hundred and twenty-six sonnet sequence: poetry and progeny versus aging and death. For Shakespeare, Time, capitalized, is the ultimate enemy. He calls Time, variously, never-resting, wasteful, bloody tyrant, coward, devouring, swift-footed, old, cruel, confounding, sluttish, injurious, thievish, filching, crooked, and, finally, fickle.

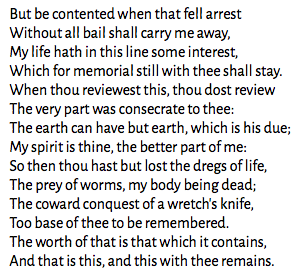

In Sonnet 126, “Time’s fickle glass” treacherously shows us youth one moment and wrinkles the next. In Sonnet 74, Shakespeare sees his own body becoming the “coward conquest of a wretch’s knife” taken dishonorably as it were from behind. In Sonnet 12, he warns Southampton that Time’s scythe is a terrible weapon against which nothing but babies “can make defense.”

In Sonnet 15, Shakespeare declares all-out “war” on Time. His reason: love. His weapon: art. Shakespeare will do battle with Time armed with only his pen.

And all in war with Time for love of you

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

As Queen Elizabeth’s reign entered its final decade, Shakespeare celebrated his love for a noble child, calling him variously, the world’s fresh ornament, most rich in youth, beauteous and lovely youth, thy mother’s glass, tender churl, beauteous niggard, profitless usurer, possessed with murderous hate [childlessness = murder], love, my love, sweet love, my true love, Dear my love, Lord of my love, Suns of the world, my all-the-world, all my art, my sovereign, my Rose, my all, all the better part of me, too dear for my possessing, Time’s best jewel, fair friend, sweet boy, and, finally, O thou my lovely boy.

The sonnets were private, shared at first only with a select few; they were almost lost. How we got them, how they prevailed against Time’s scythe — the sonnets’ origin story — is as fascinating as one might expect. Indeed, the story is as good as any Shakespeare drama.

A Story Rarely Told

At the end of the sixteenth century, a young earl was living in a maelstrom of political intrigue. From an early age, Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, weighed tempting offers and all-in risks. Shakespeare, connected somehow to this earl, offering loving guidance and unconditional support, put the boy’s/young man’s life into poetry where it would be safe from Time’s scythe.

For some ten years or more, poetry and history intertwined, involving, ultimately, a whole nation. The cast of characters includes Queen Elizabeth herself, Lord Burghley (the Queen’s closest advisor), Burgley’s grand-daughter Elizabeth, the Earl of Essex (Southampton’s friend and ally), and the Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery as well as Shakespeare and Southampton. Love and longing, power and fate, life and death, and the terrifying roller-coaster of Elizabethan politics enlivened the art of England’s greatest poet.

Shakespeare knew all about his greatness — he expected his skill to go toe to toe with Time itself. In Sonnet 32 Shakespeare speaks ironically of his “poor rude lines” that might someday be outstripped by a poet with superior “style” (not bloody likely). But never, he says, will his lines be matched for “love.” Here is the highest of high compliments to his lovely boy: writing for the ages with matchless skill, his talent is nothing next to his love for Southampton.

But the boy was reckless. He lost his friend to an axe he himself dodged only by the slimmest of margins. The sonnets celebrating him hung by a thread. Eventually published, but oddly shunned, the sonnets were as good as dead for more than a century. Eventually, hope triumphed over circumstance and the sonnets returned, as it were, from the grave. To this day, the poems cause trouble.

Their story, the story of the sonnets themselves, has yet to end.

All’s well didn’t end well for Southampton’s friend, the Earl of Essex.

One Thousand Seven Hundred and Sixty-Five Lines of Controversy

No one involved in the modern acrimony over the sonnets is going to lose his head, but wild theories fly like pollen in early spring. The 14-line poems seem to have a Harry Potter-esque curse upon them, placing them always at the nexus of trouble.

We cannot even say with certainty to whom the sonnets were written. Southampton is a very good guess, but one can quibble if one wants to. Shakespeare’s epic poems were overtly and lavishly dedicated to the young earl making him an automatic suspect for the subject of the sonnets. The sonnets contain thirty-six lines repeated almost word for word from the first epic poem. Most importantly, the sonnets fit Southampton’s exciting life quite well. Shakespeare never dedicated anything to anyone else — Southampton was his one and only.

Thus, in 1817, Nathan Drake proposed in print Southampton as the obvious candidate for Shakespeare’s great love. The subject of the sonnets, whoever he is, is usually called the “fair youth” as opposed to “Southampton.” We shall use Shakespeare’s term — “lovely boy.” But we shall assume Drake was right: the “lovely boy” is almost certainly the Earl of Southampton.

We gamble when we assume, but our modest wager rewards us: a coherent and dramatic story is our payback.

Honor, Public and Private

In 1590, Shakespeare’s plays had yet to enliven a printing press. Even so, the bard’s voice had already found its way into the local vernacular: in 1589, the quick-witted hipster Thomas Nashe giddily quipped about “whole Hamlets, I should say handfuls, of tragical speeches.” Nashe had evidently seen Hamlet, talked about Hamlet, and heard what others had to say about Hamlet with enough frequency to make Shakespeare the target of his fun-loving pen.

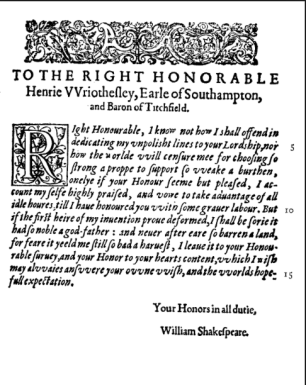

Nashe did not mention Shakespeare by name which is not surprising given the lack of Shakespeare publications at the time. Finally, in 1593, in the midst of the Southampton marital negotiations, Shakespeare introduced himself to the public with his epic poem Venus and Adonis. It featured a beautiful young man who refuses love and dies. Shakespeare and Southampton are now linked in the public eye.

If your honor seem but pleased,

I account myself highly praised,

and vow to take advantage of all idle hours,

till I have honored you with some graver labor.

Shakespeare finally in print.

Venus and Adonis was a smashing success going through sixteen editions over the next fifty years. In contrast, the Make-Us-a-Baby Sonnets remained in what one might call their zeroth edition for nineteen years or so. They were not for public consumption.

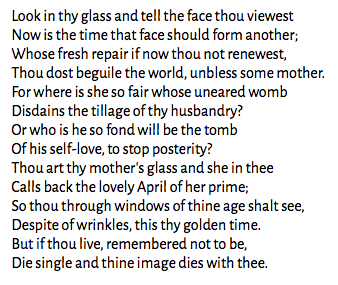

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest

Thou dost beguile [deprive] the world, unbless [sadden] some mother.

For where is she so fair whose uneared [virgin] womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

The pretty young earl would be keeping his husbandry to himself for the time being, thank you very much.

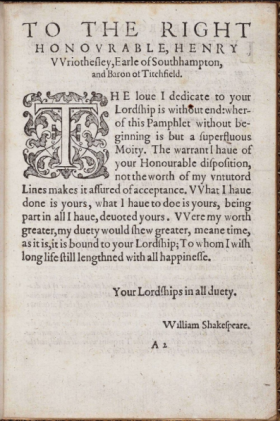

In 1594, a second epic poem, The Rape of Lucrece, was published. Meanwhile, plays waited in the wings, performed but not published. The Lucrece dedication made the Venus dedication seem reserved.

THE love I dedicate to your lordship is without end . . .

What I have done is yours, what I have to do is yours,

being part in all I have, devoted yours . . .

I wish [you] long life still lengthened with all happiness.

Shakespeare’s second, and final, dedication.

Lucrece went through eight editions in fifty years, another smashing success. Meanwhile the sonnets continued to press for baby earls.

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death’s conquest and make worms thine heir.

. . .

Make thee another self for love of me

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

The “worms” in this sonnet mark the first of four appearances of the hungry creatures who feast on the newly dead. For Shakespeare, the metaphorical sound of worms licking their chops was enough to make anyone want a child. Worms took their bows on Shakespeare’s stages as well.

In Hamlet, worms play their familiar role: they eat the unfortunate Polonius whom the protagonist has stabbed. Lord Burghley was born in 1520; the “Diet of Worms” took place in 1521. This wormy event was a diet (convocation) held for Emperor Charles V in a small town in Germany called Worms. The convocation marked the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. The following lines may be a nod to Burghley’s birth date as he is the most likely inspiration for the Polonius character.

Hamlet is asked where Polonius is and he replies, rather concisely, “At supper.”

But then he elaborates.

“Not where he eats, but where he is eaten. A certain convocation of politic worms are e’en at him. Your worm is your only emperor for diet. We fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots. Your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service—two dishes, but to one table.” Hamlet Act 4, Scene 3.

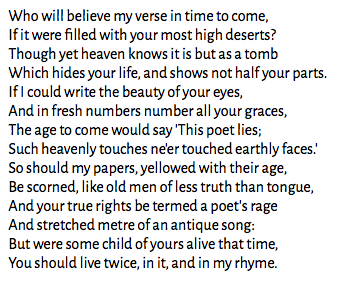

Finally, sadly, in 1594, Southampton came of age and refused his betrothed. Brushing aside the failure, Shakespeare continued the poetic celebration of his lovely boy over the next decade. The sonnets would be a “monument” of “gentle verse,” he promised, “filled with your most high deserts,” strong enough to withstand “war’s quick fire,” able to leap tall buildings in a single bound . . .

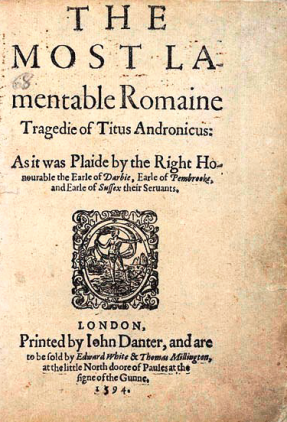

If Shakespeare felt similarly about the lasting nature of his plays, he never said so. In 1594, the plays began appearing in printed editions without a byline and without dedications. The sometimes-garbled plays did not always (or ever) benefit from authorial oversight. The first play to be published was the anonymous Titus Andronicus. Probably everyone knew whose it was despite the lack of byline.

Titus Andronicus was performed by three different acting companies. This edition was reasonably accurate.

In 1598, Southampton married a woman of his own choosing. The Shakespeare byline now appeared on the plays, but those who wanted additional epic poems or additional personal dedications were to be disappointed.

Meanwhile, work on the sonnets progressed as rumors of their existence leaked. Francis Meres spilled the beans in 1598, “Witness his sugared sonnets among his private friends,” he wrote along with praise for Shakespeare and a list of plays including both Love’s Labors Lost and Love’s Labors Won the later of which we assume is a Shakespearean labor lost.

Mr. Meres, despite his familiarity with Shakespeare’s work, clearly hadn’t seen the sonnets himself. No one who was telling had. Referential quips from the local quipsters about “whole seasons of summer’s days” would have to wait. The sonnets were private for another eleven years.

For Shakespeare, this privacy was merely a temporary expedient. If we are to believe the sonnets, nothing was more important to Shakespeare than these poems, their noble subject, and their eventual publication that would ensuring the immortality subject, words, and author.

And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand [up to Time]

Praising thy worth, despite his [Time’s] cruel hand.

. . .

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see

So long lives this and this gives life to thee

. . .

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

when tyrants’ crests of tombs of brass are spent.

. . .

Not marble not the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme.

Very nice. But even if you are the greatest poet in England, even if you are literally Shakespeare, there are no guarantees when it comes to outliving marble monuments if your glorious subject insists on kicking around tectonic plates like they are unruly servants.

To say the Earl of Southampton, the “lovely boy” of the sonnets, did not behave himself is a fantastic understatement.

The Politics of Failure

When Shakespeare broke ground on the “eternal lines” that would “preserve the living record of [Southampton’s] memory,” the self-willed boy was in line to marry the grand-daughter of Lord Burghley. The puritanical Burghley was the Queen’s closest advisor and therefore the most powerful man in England.

Burghley ate “powerful rhymes” for breakfast. One would think Southampton would be pleased to accept the great man’s grand-daughter’s hand and accept an ally somewhat more powerful than lovely lines celebrating a “lovely boy.” One would be wrong.

Lord Burghley was a consummate plotter who usually got what he wanted, which was, quite often, consummation. The highest ranking earl in England, Edward de Vere, had already married his daughter, the long-suffering Anne Cecil. Now it was Southampton’s turn to gild the Cecil family name.

It was none other than the great William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and his son, Robert Cecil, who engineered the succession after the childless Elizabeth died. It would be King James of Scotland and the foundation for the eventual unification of Scotland and England would be laid courtesy of the Cecil machinations. Southampton would have been wise to ally himself with this powerful family.

He did not. Refusing Burghley, refusing the silent-to-history, but clearly willing teen-aged Elizabeth Vere in 1594 was ill-advised on Southampton’s part, but it wasn’t quite crazy. No. Crazy came later.

William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the man who eventually determined who would succeed Queen Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudor Rose monarchs.

Plays vs Poems

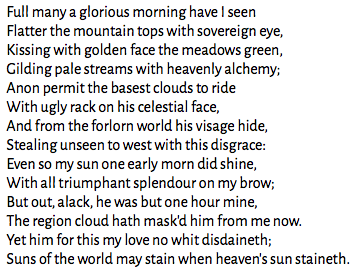

Elizabeth Vere married, in due course, the Earl of Derby. Southampton remained the subject of new sonnets for which marriage was a far-off ideal. In Burghley’s world, Shakespeare plays remained a welcome diversion: revelers enjoyed a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the wedding of his eldest grand-daughter.

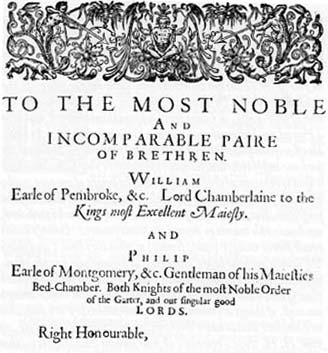

In due course, Burghley’s youngest grand-daughter, Susan Vere, married the Earl of Montgomery. It was a very Shakespearean family to be sure: Montgomery and his brother, the Earl of Pembroke, were the eventual dedicatees of the all-important First Folio — the monumental compilation that saved Shakespeare for posterity. No First Folio, no Macbeth.

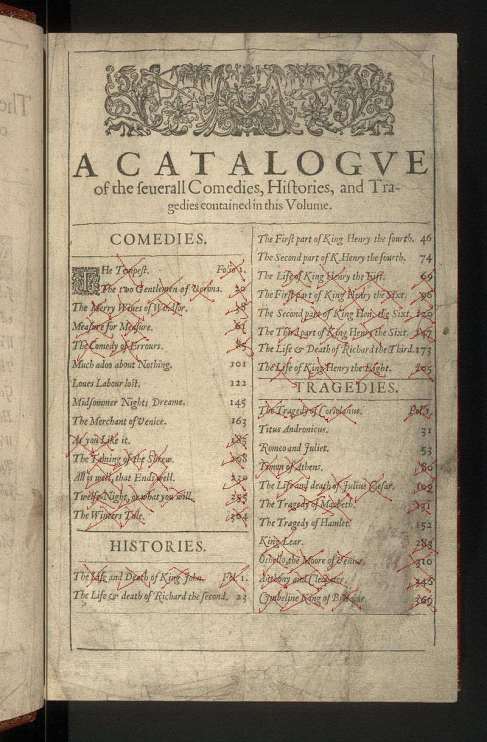

In 1623, thirty-six Shakespeare plays, accurately rendered, miraculously appeared in one stunning tome. Twenty-four of these plays had either not been published during Shakespeare’s lifetime or had been published in corrupted, error-filled versions.

Without the First Folio, you would likely never have heard of sixteen Shakespeare plays: All’s Well that Ends Well, As You Like It, Antony and Cleopatra, The Comedy of Errors, Cymbeline, Coriolanus, Henry VI part 1, Henry VIII, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, The Tempest, Timon of Athens, Twelfth Night, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, AND The Winter’s Tale.

Without the First Folio, you might have seen a horribly broken version of The Taming of a Shrew and a disastrous muddling called The Troublesome Reign of King John, but you would not get to see the real versions as these early publications were so badly butchered that they bore little or no resemblance to Shakespeare’s actual work.

Five plays published during Shakespeare’s lifetime were, at best, somewhere in the ballpark of the First Folio versions: Henry VI part 2, Henry VI part 3, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Henry V, and, even, the heartfelt King Lear.

The year before the First Folio was printed, one previously unpublished play, Othello, came out in a sort-of accurate printed version, differing from the First Folio version by only 170 lines or so.

With Othello, we have a grand total of twenty-four plays effectively missing from the canon the day Shakespeare died. To appreciate the horror of Shakespeare without the First Folio, take a look at its table of contents with the twenty-four rescued plays crossed out.

It’s a good thing someone held onto the manuscripts.

In addition to the seven plays published in various states of disrepair, twelve decent versions of plays were printed, one way or another, during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The twelve are as follows: Hamlet, Henry IV part 1, Henry IV part 2, Love’s Labor’s Lost, The Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Richard II, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, Titus Andronicus, and Troylus and Cressida (this last is included in the First Folio, but was inserted at the last minute and does not appear on the “CATALOGVE” page).

The unpredictable nature of Shakespeare publications can be amusing for modern readers: for example, the first pre-Folio attempt to publish Hamlet contained the immortal line, “To be or not to be, Aye there’s the point.” An accurate version appeared a year later. Romeo and Juliet also had an evil twin.

Bottom line, as of 1616, the year of Shakespeare’s death, the Shakespeare publication history was a godawful mess. After seven more trips around the sun, the expansion of the canon from twelve to thirty-six intact plays came about by the good graces of the “incomparable paire of brethren,” two earls who evidently knew the right people.

The two earls were joined by two of Shakespeare’s fellow members of the King’s Men acting company, John Heminge and Henry Condell. They gathered together Shakespeare plays that had already been published, plays that had never been published, and plays that had been published monstrously.

Heminge and Condell, writing in the preface to the First Folio, tell us that readers were previously “abused with diverse stolen and surreptitious copies maimed and deformed by the stealths of injurious imposters,” but now would get authoritative versions “perfect of their limbs.” The publishers, Edward Blount and William Jaggard, likewise promised in the preface that the First Folio was based on the “true original copies” of the plays.

The sonnets and epic poems were NOT included: no one knows why. Ben Jonson’s works, published by him in folio form in 1616 and thought to have inspired Shakespeare’s version, included plays and poems.

Southampton’s wild antics and disastrous politics may have played a role in the plays-only decision. By 1623, the now-fiftyish Venus/Lucrece dedicatee and the prodigal lovely boy of the sonnets, had survived his bout of extravagant incaution. He was content each morning to “look in thy glass” and see his head attached to his shoulders.

Southampton was in no position to protest the snubbing of the sonnets. Shakespeare, himself already “the prey of worms,” likewise had little to say.

And so the great poet’s unconditional love, deep identification (“my glass shall not persuade me I am old, so long as youth and thou are of one date”), and infinite esteem for the Earl of Southampton carved into fragile paper with black ink, lovingly crafted over thirteen years, the great author’s monument of one hundred and twenty-six intensely evocative sonnet-letters, those wondrous immortal lines we fawn over today were dropped like hot rocks by Pembroke, Montgomery, Heminge, Condell, Blount, and Jaggard.

The epic poems were protected by their multiple editions. The sonnets were cast adrift in the uncompromising seas of time, with no guarantee of arrival at a friendly shore, ever.

Shakespeare had been so sure of himself.

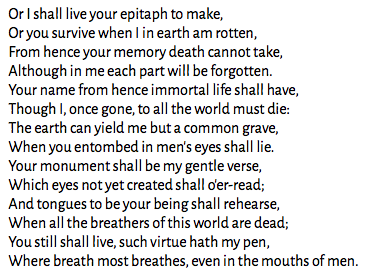

When all the breathers of this world are dead

You still shall live (such virtue hath my pen).

Now he had to rely on luck. But maybe he knew the future.

Fortune brings in some boats that are not steered. — Cymbeline, IV.iii

And so it came to pass for the sonnets. We shall see the push of fortune’s hand and we shall follow our lovely boy to Hell and back. Patience! First you must know the curse of the sonnets.

A 400-year-old Curse

How many people realize the “thee” in “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day” is a self-willed young man who wouldn’t marry properly, a young man whose rash behavior got his noble friend killed along with four unfortunate commoners? The answer is “not many” and maybe it’s just as well.

The lovely boy is still at it, you see. First we’re talking about Southampton, then we shift to Shakespeare himself. We cannot resist. We become convinced Shakespeare is talking to us as himself through the sonnets. We become amateur biographers. We begin spewing wild theories, guessing our way out of intelligent history. We reel out of control just like an earl from long ago.

Professor James Shapiro at Columbia University has a simple and sensible remedy for sonnet-itis: “I steer clear of reading these extraordinary poems as autobiography.”

Columbia Professor James Shapiro

And really there’s no choice. Shakespeare was a twenty-something commoner when he came to London in the early 1590’s and became involved with the theater as a shareholder of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. We know nothing of his relationship with Southampton. We therefore cannot place the sonnets in any kind of context.

It isn’t clear how or why Shakespeare would refer to the Earl of Southampton as “O thou my lovely boy” or as a “tender churl” or say to him “be not self-willed” or ask him to “make thee another self for love of me” or be involved in the boy’s marriage decisions or Lord Burghley’s politics.

With the uncertainties associated with any autobiographical reading of the sonnets (we can’t even say with certainty that the sonnets were written to Southampton), it makes sense to follow the lead of Professor Shapiro and virtually every other Shakespeare scholar and simply regard them as “extraordinary poems” written by an artist whose writing life is insufficiently documented to allow us to convert them into personal documents.

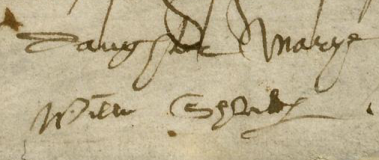

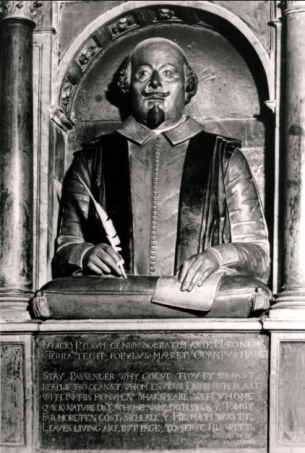

Some Elizabethan authors like Ben Jonson or Thomas Nashe wrote manuscripts and/or letters that survived. For these authors, we are fortunate enough to have signatures in books . . .

. . . and long samples of handwriting . . .

. . . giving us a place to begin, providing us with at least some semblance of context.

However, the surviving documents referring to Shakespeare do not shed light on his writing in general or on the sonnets in particular. We have legal, personal, and business records and so forth, but no manuscripts survive; there are no surviving personal letters concerning writing that might mention or allude to the sonnets. In fact, none of Shakespeare’s letters, written or received, survive.

There are a few signatures on legal documents . . .

. . . but this is not a literary document . . .

. . . and he was probably ill when he signed his legalistic will.

Shakespeare’s will didn’t mention books or manuscripts or writer’s tools such as ink, pens, desks, or shelves. The omission of books etc., makes perfect sense under the circumstances — Shakespeare’s wife and two grown daughters were not literate, so they wouldn’t have had use for such things.

We may surmise that Shakespeare simply transferred ownership of books and any manuscripts he had retained to an unknown party prior to leaving literary London around 1610 and returning to his business-oriented life in Stratford.

The people Shakespeare biographer Samuel Schoenbaum calls Shakespeare’s “townsmen” didn’t even realize their neighbor was the great writer, Shakespeare: “They probably troubled their heads little enough about the plays and poems,” Schoenbaum writes. “Business was another matter; they saw Shakespeare as a man shrewd in practical affairs.”

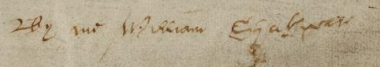

We are like Shakespeare’s townsmen in that we don’t know much about Shakespeare’s writing life. There is a monument in Stratford commemorating Shakespeare as a combination of Socrates, Nestor, and Virgil. There are the letters praising the late author written by Heminge and Condell for the First Folio. That’s all we have, unfortunately.

Shakespeare’s monument in Stratford.

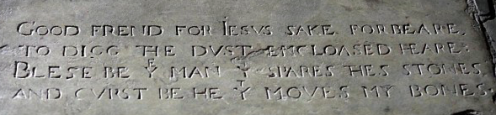

The sonnets, without any context in which to place them, are an accident waiting to happen. In fact, the accident has happened. The trouble began with another “monument” in Stratford — Shakespeare’s gravestone.

Another reminder to avoid seeking autobiography in unlikely places.

Mark Twain famously regarded the doggerel on the gravestone as an indication that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare! And thereby hangs a tale.

Hordes of present-day Mark Twains now point at the “obviously” autobiographical sonnets to continue pushing his shocking idea. They say we may seek in the sonnets answers to the “authorship question.”

Despite cool heads like Professor Shapiro’s, the grim spectacle of speculative history rears its head in all manner of surprising places. The sonnets are wielded even by Shapiro’s fellow professionals (!) as if they were the Sword of Gryffindor — an undefeatable weapon.

The controversy will never go away. That is the curse of the sonnets.

The Editor-Pirate

One day in 1609, Thomas Thorpe got his unclean hands on the celebration of Southampton Shakespeare had wrought with his pen. Imagine! The priceless handwritten copy — maybe even the originals — of Shakespeare’s long declaration of love to the one person he wished to immortalize was crinkling in the well-known editor-pirate’s trembling hands.

Thorpe only managed one printing, barely enough to allow fortune to save Shakespeare’s politically charged monument. Aside from Southampton’s history, the subject also suffered from the problem of being a “lovely boy” as opposed to a “beautiful maiden.” Bottom line: no one knows why Shakespeare’s apparently personal poetry was not published in multiple editions. Maybe his readers didn’t think much of them.

A century plus two years later, the sonnets were pulled back from history’s precipice and printed in their original form once again by one Bernard Lintott. Then, in 1780, the original sonnets with commentary were published by Edmund Malone. They have been safe ever since; in fact, thirteen copies of the original 1609 publication — six in England, six in the U.S. and one in Switzerland — survive. Maybe they really were immortal after all.

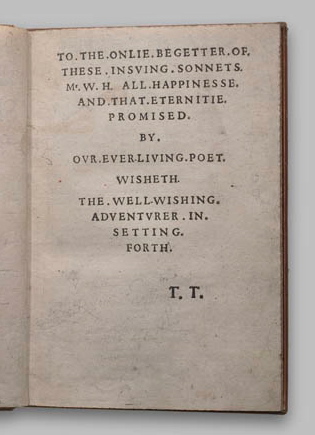

The sonnets contain no author’s dedication, but Thorpe published his own short dedication in which he wished someone called “Mr. W.H.” the same “all happiness” Shakespeare had wished Southampton all those years ago in the Lucrece dedication. Thorpe further expressed his hope that the “eternity” Shakespeare wanted for his subject would be bestowed upon this “Mr. W.H.”

Southampton’s initials are “H.W.” and, as an earl, he is not properly addressed as “Mr.” Therefore, it isn’t clear to whom Thorpe is referring. Maybe Southampton’s stepfather, Mr. William Harvey, brought Thorpe the sonnets or maybe Thorpe sought to mislead his readers. No one knows.

Actually, Thorpe’s entire dedication is confusing.

At the time, Shakespeare was ever-living sometimes in Stratford and sometimes in London. Unlike Henry the Fifth, “that ever-living man of memory,” our friend William had a few years left to him.

We forgive Thorpe his cryptic dedication, his early eulogy, and his unrepentant piracy for he gave us the sonnets.

A REALLY Bad Idea . . . or . . . The Moment You’ve Been Waiting For

With hindsight, given Southampton’s subsequent decisions, the first seventeen sonnets might have put progeny aside and more productively sung the praises of not committing treason. But then, Shakespeare couldn’t have known what his lovely boy was capable of.

In 1601, the wayward, stubborn, I’ll-marry-whomever-I-want earl was arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. Southampton and the Earl of Essex led what is known as the “Essex rebellion” wherein the two idiot earls and some of their followers attempted to control the royal succession.

Tossed into the Tower of London, watching his friends die one by one, waiting for his own date with the axeman, Southampton’s first few months of the 17th century were, shall we say, inauspicious. Here are the details of Southampton’s downfall.

As the Queen lay dying, Southampton and Essex, with an ever-shrinking group of uncertain supporters, hatched a plan to gain access to the Queen’s bedchamber. It is not clear precisely what their plan even was. In any case, they didn’t get far.

Burghley’s son, the cunning Robert Cecil, and his legendary network of spies (built by his father and as seen in Hamlet) outwitted the Southampton-Essex amateur hour. “Outwitted” used here is a charitable term employed simply because we have no wish to further insult our lovely boy. Still, putting aside the noble aim of gentleness, we must aver that we understand that the bird does not really “outwit” the worm.

Many expected the Queen to commute the death sentence of Southampton’s great friend, the popular Earl of Essex, but his head rolled as far as any commoner’s. For him, it was over reasonably quickly though his neck resisted the axe’s first two swings. Sirs Blount (no relation to the First Folio editor), Meyrick, Cuffe, and Danvers, the commoner co-conspirators also convicted of high treason, were not so fortunate as the gentle earl. They suffered greatly with their guts removed and their limbs torn from their bodies prior to the severing of their knighted heads.

The Earl of Essex before he lost his head.

Then something odd happened, something history can’t get its head (so to speak) around because there is, again, no paper trail. The Essex Rebellion had so far killed five people. Many more were energetically thanking God for having granted them the wisdom to run far and fast as the plan, such as it was, exploded in the earls’ pretty faces. One more head would, shall we say, cap the episode.

It is not recorded that anyone at this time said to Southampton, “Lovely boy, have you ever thought maybe you should have married Elizabeth Vere? Lovely boy, may I offer you some advice you might have use for in the unlikely event you are still alive tomorrow?”

But Southampton was not destined to die. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. It was a stunning development and that’s all we know about it. The Queen didn’t want to give an official reason, so she didn’t.

The sonnets may contain clues as to the reason, or, if there is no path to the precise reason for a fool’s deliverance, there may at least be an indication of the mechanism by which Southampton’s good fortune manifested itself.

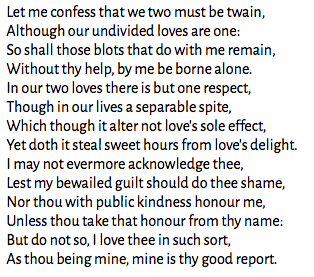

Sonnet 87 contains the following interesting lines:

So thy great gift, upon misprision growing

comes home again on better judgment making.

Misprision of treason is an Elizabethan term for failure to report treasonous activity. It is a serious crime, but NOT a capital crime. From Southampton’s and Shakespeare’s point of view, it is certainly a “better judgment.”

King James I of England. This man was going to be King, if necessary over Southampton’s dead body.

We may never know precisely who Southampton was. We certainly don’t know why he and Essex thought they could control the succession or who they favored for the Queen’s successor or even whether that was the goal of their ill-conceived plot.

We know Essex’s great-grandmother was the sister of Queen Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn. Southampton’s baptismal record is missing, but, as far as we know, his bloodline wasn’t as impressive as Essex’s.

Elizabeth died in 1603 without an heir and without a clear successor while Southampton languished in the Tower. Meanwhile, Essex’s remains were making the local worms fatter and fatter. We may never know why the Queen spared Southampton but not Essex.

Southampton was outrageously lucky to live to be this old. If the painting is accurate, he was a lucky alcoholic.

We know one more thing about Southampton. The treasonous wretch was NOT just not executed. The vile traitorous scum was NOT just singled out as the survivor of a conspiracy that targeted the crown itself. Southampton must have had some BIG magic. For when King James ascended the throne, he was actually RELEASED from the Tower, his life sentence thrown out althogether! Not only that, his earldom and all his lands were restored to him AND, that same year, James made him a Knight of the Garter — to this day a singular honor.

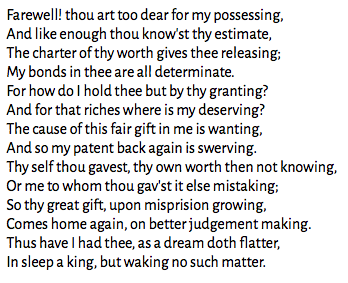

The ebullient Sonnet 107 celebrating a rather improbable release is central to this part of the story. As usual, we don’t know why King James was so sweet on Southampton. The sonnet seems clear enough though: The Queen has died (the mortal moon hath her eclipse endured), the feared civil war over the succession did not happen (the sad augurs mock their own presage), Southampton is free (supposed as forfeit to a confined doom . . . my love looks fresh), and the author will defeat death through his words (death to me subscribes [succumbs] . . .).

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world dreaming on things to come,

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confined doom.

The mortal moon hath her eclipse endured,

And the sad augurs mock their own presage;

Incertainties now crown themselves assured,

And peace proclaims olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh, and Death to me subscribes,

Since, spite of him, I’ll live in this poor rhyme,

While he insults o’er dull and speechless tribes:

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent.

It is hard to imagine a man more fortunate than Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. Celebrated in Shakespeare’s incomparable sonnets for all eternity even though he refused to marry properly, his death sentence commuted to life in prison by the Queen even though he stood convicted of high treason, his lifetime in the Tower miraculously transmuted to freedom and a restored earldom even though he had opposed the succession of James of Scotland, Henry W. is the kind of guy I’d pay a lot to travel back to see.

I’d sit down with him and we would have tequila — he’d be game I’m sure — and I’d ask him what he wants out of life. My guess is he’d say, “To be King on my own terms,” before downing shot after shot. I would be nothing if not encouraging. “To your health,” I would say loudly and often. If only . . .

Only the finest for my lovely boy.

Logic

In 1900, there were two worlds. In one, lived the scientists who believed in the atomic theory. In the other, lived those clinging to the eminently sensible, but wrong, theory that matter was continuous and not (pish-posh) largely empty space. One group busily calculated the radii and masses of the newly discovered atoms. The other group grew old, weakened, became wrinkled, and died.

Today, there is a world of logic inhabited by Shakespearean actors Sir Derek Jakobi, Mark Rylance, Sir John Gielgud, and Michael York. Also in this world are thoughtful observers Sigmund Freud and Mark Twain. Sharing space with them are writers Henry James, Walt Whitman, and Nobel laureate John Galsworthy. At the head of the table, sit U.S. Supreme Court Justices Blackmun, Powell, O’Connor, Stevens, and Scalia.

The Shakespeare Authorship Research Center at Concordia University in Oregon is currently the best example of serious academic discussion of that annoying “authorship question.”

Of all the inhabitants of this world, perhaps the most extraordinary is the 18th Baron Burghley himself, Michael William Cecil, whose ancestor played a central role in the Shakespeare saga. He is a signatory to something called the “Declaration of Reasonable Doubt” in which the “doubters” codify their objections to the “official” viewpoint.

And there is Roger Stritmatter whose 2001 dissertation at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst on one aspect of the authorship question is the first doctorate awarded in this particular world of logic.

Dr. Michael Delahoyde at Washington State University, another heretic, was succinct and not 100% polite in giving his opinion about the notion that the sonnets are not autobiographical. The word he used was “insane.”

Finally, we have Diana Price, the Elaine Morgan of the authorship question. The discussion above of the paper trails left by Elizabethan authors is based on her seminal work, “Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography.”

Of course, the vast majority of Shakespeare scholars still characterize as a crackpot theory the notion that some nobleman or other may have used the Shakespeare name as a pseudonym and later the man himself as a front.

I must apologize for misleading you, dear reader. In the section featuring the redoubtable Professor Shapiro, I felt it my duty to present the mainstream viewpoint as forcefully as I could. It may indeed have been convincing or the argument may have crumbled under its own weight — either way, you mustn’t blame me. It is what it is.

Could Shakespeare of Stratford have written the sonnets? Maybe. Did the man who wrote no letters, who owned no books, who raised illiterate children, say to the Earl of Southampton, “make thee another self for love of me”? Maybe. Are poems written to someone who is obviously the love of your life — poems kept private for a decade and more — really not personal? Not bloody likely.

On the other hand, let us be fair. Maybe the self-taught genius from Stratford didn’t have time to write letters or teach his country girls to read as he simultaneously rose within the literary and acting worlds of Elizabethan London. He may have borrowed his books, despite being rich. It is possible he felt a fatherly or brotherly affection toward a teenaged earl whom he met (perhaps while performing at court) and with whom he became involved without attracting any attention at all. And we must not forget we have the option to steer clear of reading the extraordinary poems as autobiography just as Professor Shapiro does. There are many possibilities. For example, the sonnets may have been commissioned by a relative of Southampton. Or the characters in the sonnets could be fictional. Anything is possible, right?

Um . . . well . . . maybe not anything.

Here are twenty-four key sonnets. And here too is some personal advice from your friendly author.

Listen not to those with the trappings of authority for underneath their trappings they may be as brilliant as Portia or as foolish as Dogberry.

You need not immerse yourself in Elizabethan trivia, for the mantle of expert is hardly worth the weight it exerts on your shoulders.

As a human being, you possess a perfectly natural and perfectly extraordinary understanding of context. And to read the sonnets is to be carried away by an avalanche of context.

Dare to read the sonnets.

Fear not the avalanche, for I guarantee that you shall arrive where-ever you are going in one roused piece.

Happy reading.

I. 1, 2, 3, 17: Get thyself married that thou may’st make for us an heir.

II. 15, 33, 18, 55: You are the most important thing in the universe and you will live forever in these lines.

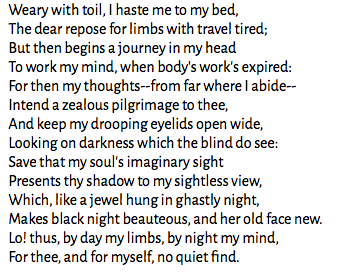

III. 22, 62, 63, 73, 74: As I age, I think of you for you and I are one.

IV. 66, 81: I am writing under a pseudonym (sorry, Jimmy).

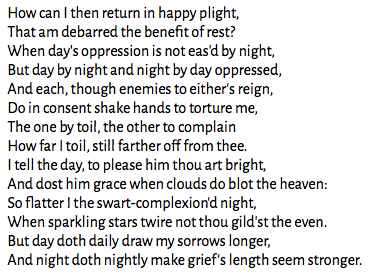

V. 27, 28, 35, 36, 87: Arrest, trial, death sentence, misprision of treason.

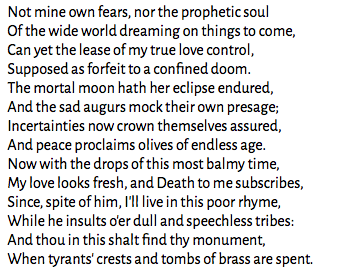

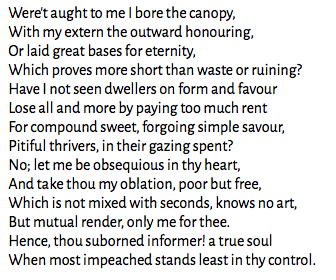

VI. 107, 125, 126: Release and peace; I bore the canopy in a royal procession; O thou my lovely boy . . .

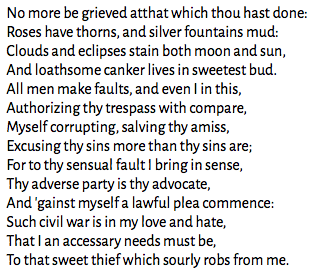

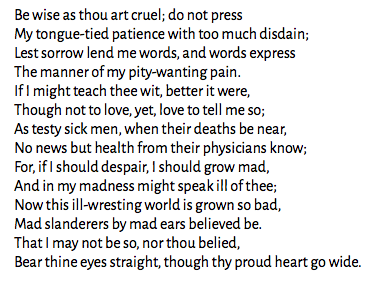

VII. 140: Another twenty-eight sonnets were written to the mysterious “Dark Lady.” Unlike the case of the first 126 sonnets written to the Fair Youth (Southampton), there is no strong contender for the identity of the Dark Lady. Sonnet 140 is deliciously dramatic though it is far from clear what it means if anything.

I. Get thyself married that thou may’st make for us an heir.

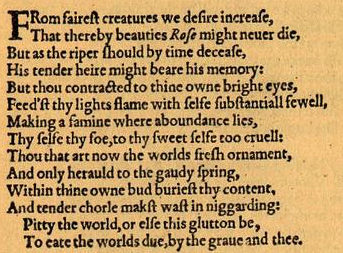

This is how Sonnet 1 looked originally.

II. You are the most important thing in the universe and you will live forever in these lines.

III. As I age, I think of you for you and I are one.

IV. I am writing under a pseudonym (sorry Jimmy)!

V. Arrest, trial, death sentence, misprision of treason.

VI. Release and peace, I bore the canopy in a royal procession, O thou my lovely boy . . .

VII. The Dark Lady — Careful or I’ll Spill the Beans

Truth

Those who believe the question has moved into the “how big are atoms” stage have a candidate for the actual author of the plays and poems and they are exploring his life for clues.

Southampton was supposed to marry Lady Elizabeth Vere, the eldest daughter of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Oxford’s youngest daughter, Susan, married the Earl of Montgomery, one of the two earls who were the dedicatees of the First Folio. The 24 unpublished manuscripts may have come courtesy of Susan Vere.

In 1582, Oxford’s brother-in-law went to the Danish court at Elsinore as an ambassador. When he came back, he wrote a private report of his experiences which survives. In the report is the setting for Hamlet. The report also mentioned a number of Danish courtiers by name. Two of the names happened to be Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

On the other hand, these are common Danish surnames, so this may mean nothing.

Edward de Vere got Anne Vavasour, one of the Queen’s maids of honor, pregnant. The Queen was not pleased. In 1581, Edward, Anne, and their guiltless infant spent two months in the Tower contemplating their sins, committed or inherited. After they were released, their families and friends had words. Swords crossed on the streets of London. People died.

Of course, family feuds have never been uncommon.

If Oxford was Shakespeare, the vicious parody of Lord Burghley in Hamlet makes perfect sense. Oxford lived much of his life under the thumb of of the great lord. He had plenty of reason to hate him and more than enough knowledge of the man to create the parody which ends with the protagonist killing Polonius and cruelly jesting before the corpse had cooled.

But then Lord Burghley was well known in London and gossip travels far.

Truth is truth though never so old

and time cannot make that false which was once true.

— Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, letter to Robert Cecil

Nay, it is ten times true,

for truth is truth to the end of reckoning.

— William Shakespeare, playwright and poet, Measure for Measure, V.i

I give unto my wife

my second-best bed with the furniture.

— William Shakspere of Stratford, actor and businessman, Last Will and Testament

Blessed be ye man that spares these stones

And cursed be he that moves my bones.

— William Shakspere of Stratford, actor and businessman, Gravestone

Henry Wriothesley (Lord Southampton) rejected the overtures of marriage to Edward de Vere’s daughter, Elizabeth. The match appeared to be proposed by Edward’s father in law, William Cecil (Lord Burghley) who Edward didn’t care for and the feeling was mutual. Southampton and de Vere may have been lovers so it would be understandable that it would have been troublesome if Southampton had married de Vere’s daughter.

Why would de Vere want to be anonymous is he was truly the author of the plays? I’ll have to watch the movie, “Anonymous”.

Without direct evidence, all we can do is speculate. Sonnet 66 with its “art made tongue-tied by authority” line implies enforced anonymity. My point is if the sonnets explain what was so special about Southampton, the author would have to (1) remain anonymous and (2) delay publication.

The sonnets were finally published in 1609 but only came out in one edition unlike the epic poems which had multiple editions following quickly upon the first edition. It is possible the sonnets just weren’t popular or that that kind of poetry wasn’t in fashion by 1609.

I think the “not popular” and “out of fashion” arguments are nonsensical. Shakespeare was extremely famous in 1609 and the sonnets are obviously his most personal writings. Maybe people in 1609 were different from people today, but everything I know about human beings says the personal writings of the most famous author in the land would be snapped up in large numbers and would come out in multiple editions.

It is difficult for me to get across how ridiculous I think the “out of fashion” argument is. I realize it is speculation, but an order from King James could easily stop subsequent editions of the sonnets. Saying there were no subsequent editions (until many, many years later) because “people just didn’t want to read them” is like saying someone spilled bag filled with gold coins on the street and people just walked on by.

Like so much of the traditional view of the authorship question, the unpopular-sonnets theory just sounds like another brilliant deduction from what Mark Twain called “the reasoning race.”

Best,

Thor